Growers typically don’t like paperwork, but an ever-increasing number of surveys has many asking: Why should we do them all?

“A lot of it’s repetitive,” said Rick Adams, a third-generation apple and pear farmer in Cowiche, Washington. He farms 20 acres and doesn’t have a human resources department to dig up records for surveys. It’s just him. “If you do one, why do you need to do another one? I mean, it takes a lot of time,” he said.

Like many aspects of American society today, agriculture runs on data. And that means data collection, often in the form of surveys asking growers how much they produce, what they pay, which chemicals they apply and how much they spend. It ranges from the required federal ag census to the regular emails requesting information from research and extension staff trying to assess the scale of a production concern or meet grant requirements.

The Washington Farm Bureau appreciates the need for data but also worries that the expanding lineup of surveys is overwhelming growers, making growers even less likely to participate, which risks making the statistics unreliable.

“There is an understandable frustration for farmers to be asked to leave off farming and assist in helping the government produce such unreliable narratives,” said Richard Clyne, the organization’s director of safety and claims.

However, some federal agencies have listened and begun looking for ways to streamline, he added.

Groups sending surveys acknowledge the time requirement but urge growers to remember the benefits that come from more accurate industry information in the hands of policymakers, researchers, regulators and farmers trying to make business decisions.

Part of farming

Agricultural surveys have been part of farming since 1791 when then-President George Washington wrote to landowners asking for information about yields, land prices and other details, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture National Agricultural Statistics Service.

Chris Mertz sympathizes about paperwork.

“Yes, it does take a fair amount of time,” said Mertz, the Northwest regional director of the USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service, or NASS.

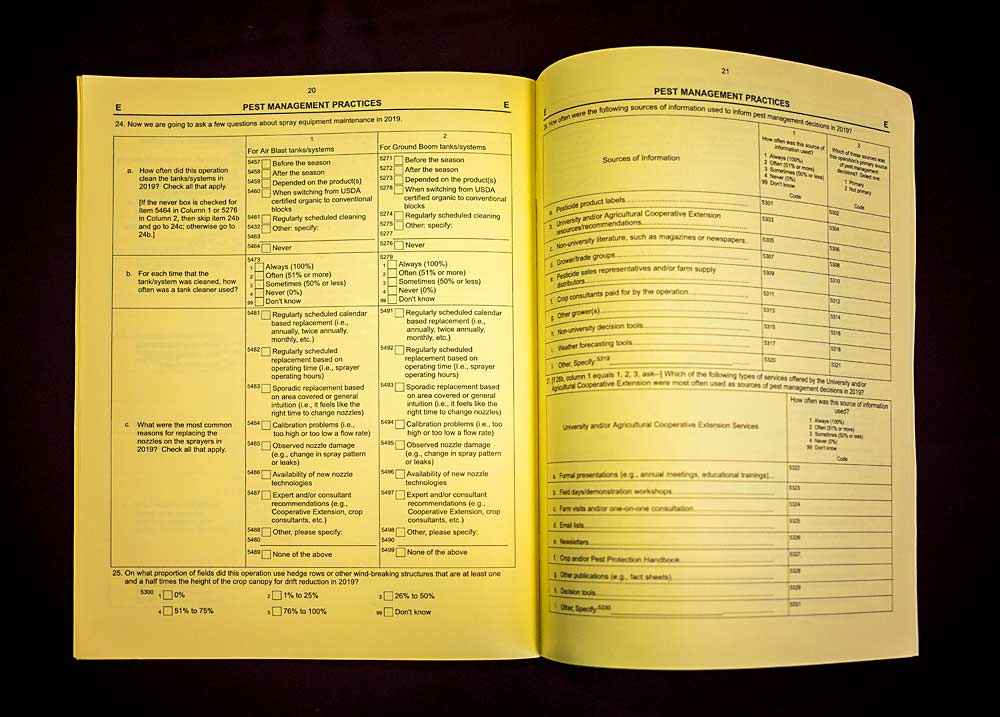

The agency conducts hundreds of surveys per year. Staff enumerators try to streamline them for growers, often sending out pre-survey letters and setting up phone appointments. Some surveys require in-person interviews, so enumerators also eventually knock on doors.

Small growers such as Adams may feel the burden more acutely, but larger companies are actually more likely to receive a survey because they have a larger proportional impact and have a diverse lineup of crops, Mertz said.

He implored growers to keep in mind the benefits of surveys, which provide unbiased information for policymakers, farmer advocates and anybody else who takes the time to read them. “It would be hard to overestimate the importance of NASS’s work or its contribution to U.S. agriculture,” the NASS website states.

The Census of Agriculture, which NASS conducts every five years, is mandated by law, as well as any follow-up or auxiliary surveys related to the ag census.

All of NASS’s other surveys are voluntary. One of them is a twice-yearly Agricultural Labor Survey, asking for total hours worked, total employees and a total payout to tabulate average wages. That survey is used by the U.S. Department of Labor to annually set the Adverse Effect Wage Rate, or AEWR, a minimum wage by region for H-2A foreign guest workers.

Meanwhile, Washington’s Employment Security Department runs a variety of employment surveys, all of them optional. The one growers probably know best is the Agricultural Peak Employment Wage and Practice Survey. With it, the state agency collects domestic worker wage information from the workers and growers during harvest, which the U.S. Department of Labor uses to set prevailing wages that are specific to states, crops and even the style of work. For example, harvest on a high-density trellised apple orchard has a different prevailing wage than on a low-density orchard of free-standing trees.

Thus, the federal Labor Department is using two different grower surveys to set two different wage mandates. By law, growers must pay the highest among the AEWR, the prevailing wage, a collective bargaining threshold or the state’s minimum wage.

Several fruit production companies in Washington sued the U.S. Department of Labor in 2019 over prevailing wage increases, citing among their concerns the methodology and findings of the state’s harvest wage survey.

The Employment Security Department shapes its survey with input from labor advocates and growers, said Steven Ross, labor market information director. Many strategies have come directly from producer feedback, he said, while some agency staff have tried their hand at apple picking, just to better understand the industry. He encourages growers to attend the agency’s quarterly stakeholder meetings and otherwise communicate with staff about their concerns.

Most importantly, Ross urges all growers to participate in spite of the time constraints and frustrations. That’s the best way to make surveys more accurate, he said.

“Participation is incredibly helpful and it leads to consistency,” he said. “When we’re surveying a population, the more responses we get, the better we can speak to that population.”

Prioritize

Grower groups, the ones working directly on behalf of growers, not only use survey data but sometimes collaborate with NASS to conduct more surveys.

In 2017, the Washington State Tree Fruit Association and the Washington Winegrowers Association hired NASS to run an acreage and variety survey, aimed at giving growers, integrated fruit companies and the entire industry information about the near future. Other grower groups, such as the Washington Apple Commission, the Pear Bureau Northwest and the Washington State Fruit Commission have tapped the data.

Recognizing growers’ time constraints, Jon DeVaney, president of the tree fruit association, suggests growers prioritize by first complying with mandatory requests for information. After that, pay attention to the surveys that will benefit them. The payoff may be indirect, but a well-informed industry helps individual farmers in the end, he said. A good survey should clearly state how the information will be used.

“Everyone needs to evaluate requests for information based on … what’s the intended purpose and whether it’s in your interest or not,” said DeVaney.

That can be hard to trust, said Lesa Bland of Cashmere, Washington.

Some surveys don’t feel beneficial, said Bland, who owns a small pear orchard with her family and does contract accounting for several other Wenatchee Valley producers. A lot of her neighbors have similar distrusts. They take particular aim at wage surveys because mandated wages have increased steadily in recent years, driving up their production cost for labor.

“I have gotten to where if it’s not mandatory, I don’t do it,” she said.

About five years ago, Wayne Reiman, a fourth-generation pear grower from Dryden, Washington, quit paying attention to questionnaires in the mail and only responded to phone inquiries. About three years ago, he answered his last phone survey.

No single questionnaire puts him over the edge, he said, but lump them together and they add up to a lot of paperwork and time he’d prefer to spend pruning, fixing equipment or performing other farming duties.

“We’re just feeling harassed by it now,” he said.

—by Ross Courtney

Related:

—Growing by the acres

Leave A Comment