Scott McDougall, right, discusses the growth of first-leaf Honeycrisp trees on the Geneva 890 rootstock during a tour of a rootstock trial at Legacy Orchard in East Wenatchee led by Tom Auvil, left. (Geraldine Warner/Good Fruit Grower)

As the volume of Honeycrisp produced in Washington continues to increase, growers who are planting the variety want the trees to come into production as quickly as possible while the fruit still sells at high prices.

But if Honeycrisp trees are cropped too soon, they will stop growing and never fill the space, limiting future production.

That’s why McDougall and Sons won’t crop the trees until the fourth leaf.

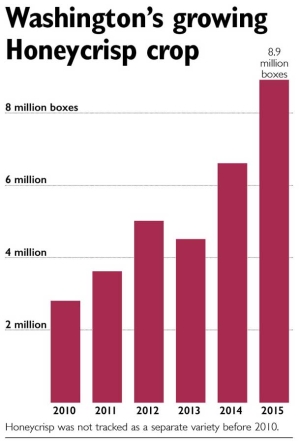

Washington’s 2015 Honeycrisp crop is estimated at just under 9 million boxes, triple the volume five years ago.

Volume has tripled in the past five years. Source: Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission (Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower)

At the company’s new Legacy Orchard on virgin ground in East Wenatchee, McDougall planted Honeycrisp last spring on the relatively weak Malling 9 337 rootstock. The trees are two feet apart on a steep V-shaped system.

Scott McDougall, company co-president, said he chose M.9 337 because of the closeness of the planting and to avoid needing to use growth regulators to slow down vegetative growth.

After the first season’s growth, McDougall said he wished the trees had more vigor, though he knew he’d be happy with them once they’d grown to the top of the trellis.

Based on past Honeycrisp plantings, he’s found that the weaker the rootstock, the less risk of bitter pit, to which the variety is particularly prone.

However, at a McDougall orchard in Quincy, trees on Budagovsky 9 grew too slowly and dirt had to be mounded around the trunks to encourage scion rooting.

When the trees did finally fill the space, though, the fruit had very little bitter pit and the fruit was about two box sizes smaller than on other rootstocks, which is desirable with the large-fruited Honeycrisp, he said.

Rootstock trial

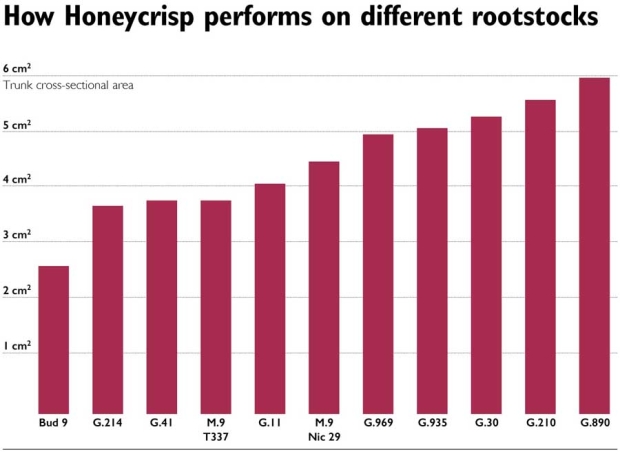

Relative growth of Honeycrisp trees after the first growing season in a rootstock trial in East Wenatchee. Source: Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission (Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower)

At the Legacy Orchard, the company also planted a rootstock trial last spring in collaboration with Tom Auvil, research horticulturist with the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission. Bud 9, M.9 337 and M.9 Nic 29 are being compared with Geneva 11, 30, 41, 210, 214, 890 and 989.

Auvil and McDougall led a tour of the planting this fall. After the first season’s growth, trees on Bud 9 were the smallest.

Trees on G.11 were slightly bigger than those on M.9 337 and should be more productive, Auvil said.

Trees on G.890 were the largest. G.890, one of the more vigorous Geneva rootstocks, is reported to be resistant to fire blight and woolly apple aphid and tolerant of replant disease.

Trees on G.890 grow very quickly, Auvil said. Though the rootstock might resemble Malling-Merton 106 in vigor, it is far more precocious.

As soon as they are cropped, trees on G.890 should calm down immediately. In fact, it might be necessary to crop them in the third leaf to slow down the growth.

The vigor might make the fruit susceptible to bitter pit, though it will take a couple of crops to find out, he added.

In the trial at Legacy, some of the bottom limbs on the G. 890 trees were 2 feet long after the first leaf.

Auvil said they should be cut back to stubs about 4 to 6 inches long, otherwise they will detract from the tree’s ability to grow vertically to the top wire of the trellis.

Virgin soil

McDougall noted that growers have been frustrated by the lack of availability of Geneva rootstocks for commercial plantings. Also, rootstock performance depends on the site and whether it’s virgin soil or not.

In a replant situation at Bray’s Landing, G.890 was less vigorous, though the trees were still larger than those on M.9 337.

At Legacy, he could see the advantage of using G.890 for Honeycrisp. “As the volumes go up, the opportunity is going to be limited, so this might be the better system in the future.

“If I knew with 890 you could get it to the top in three years, crop it, shut it down, and it didn’t have a lot of bitter pit, then it would be a race to the top and get that thing fruiting rather than what you see behind me,” he added, indicating the slower growing planting on M.9 337. •

Leave A Comment