Options abound for wineries and vineyards seeking to certify their sustainable practices, but regenerative agriculture certification is gaining traction in California vineyards.

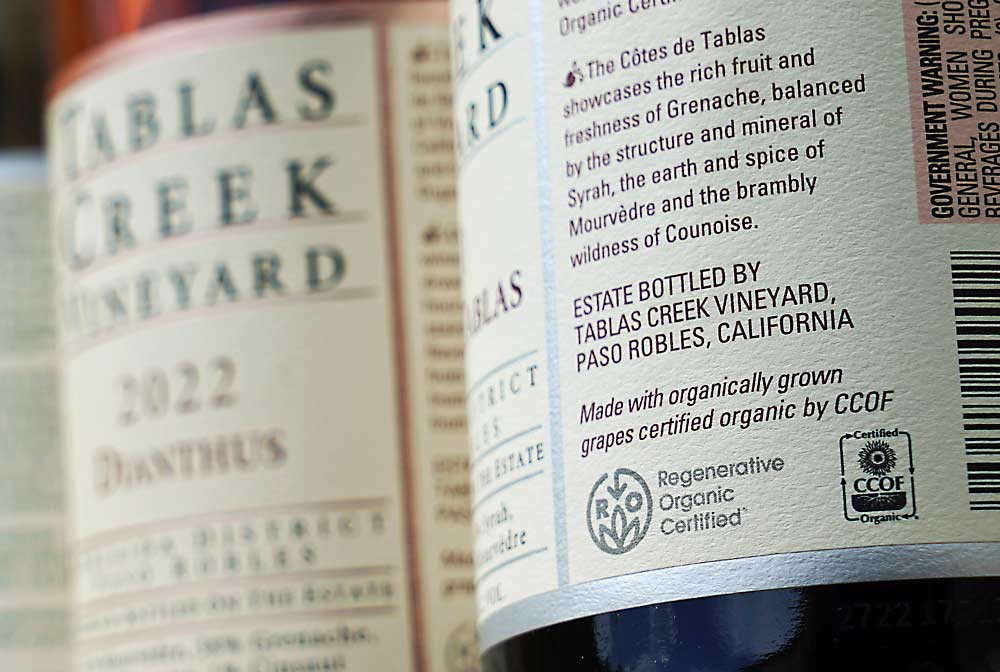

In 2020, Tablas Creek Vineyard of Paso Robles became the first vineyard in America to be Regenerative Organic Certified (ROC), and in 2022, Bonterra Organic Estates in Hopland became the largest vineyard to earn the ROC title. The California-based Regenerative Organic Alliance, which was founded in 2017, offers its certification to growers of all kinds and in countries around the world.

The alliance outlines its vision as a focus on soil health, animal welfare and social fairness — similar in some respects but different in others from sustainability-focused programs often developed specifically for vineyards.

That emphasis on fair labor practices is what drew Tablas Creek to the ROC program.

“I was reading through its soil-health pillar and animal-welfare pillar, and thinking we’re already doing a good portion of what this certification requires, so this is just another certification that means more time at my desk and less time in the field,” said Tablas Creek viticulturist Jordan Lonborg. “Then I got to the social-welfare pillar, and I knew pretty quickly that it was something that we had to be a part of.”

Bonterra opted to apply to the ROC program because of its organic foundation and growing reputation, said Joseph Brinkley, the company’s director of regenerative farming.

Regenerative in practice

The Regenerative Organic Alliance launched the certification program after a pilot project with a handful of vineyards. Now, 10 U.S. vineyards, eight in California, one in Oregon and one in Washington, have been certified, according to the program’s website.

Brinkley said there is a lot of buzz around regenerative agriculture, but it takes a certification program to ensure the term translates to practice.

While Bonterra didn’t have to change its farm practices significantly to meet ROC standards, it did have to document just about everything.

“It requires in-field soil testing (such as) evaluating the amount of roots, the amount of macroarthropods you can see, the smell, the feel, the texture,” Brinkley said.

Though the data takes time to gather, it also provides a wealth of information to the farm.

“It’s stuff we’ve all done at some point, but maybe not as frequently as we could, so this framework does allow you, and even forces you, to spend a bit more time and think about things differently, which is definitely of benefit,” he said.

The certification audit also includes ensuring employees and contracted workers are available for interviews about safety and labor practices.

Lonborg, of Tablas Creek, describes the social-welfare pillar as including important things that do not fall under a traditional organic certification. He pointed to steps, such as holding full-staff discussions and meetings, educating workers on their rights, and “really breaking down a lot of walls that have been created over time” by an industry that hasn’t historically always given its workers their due.

The ROC also has a living-wage requirement, which certified vineyards may meet through pay and perks or just pay. Tablas opted for full pay (the highest, or “gold level” of the certification). Although the vineyard forecasted the wage increase would result in a $200,000 annual bump to its labor budget, Lonborg said the cost has actually — and surprisingly — decreased by about $20,000 a year.

“We’re only a couple of years into this living-wage minimum, but if this continues, it’s going to be a really powerful thing to show to the rest of the community: If you want to save money, pay your workers more,” Lonborg said. “You create a sense of ownership and pride, and a work ethic on the property, when people know they’re going home with a good paycheck.”

Sticking with sustainability

Niner Wine Estates was already incorporating multiple “green” practices in its operation when it became among the first vineyards certified under the Sustainability in Practice, or SIP, standard in 2016. SIP is offered to U.S. vineyards, wineries and wines through the nonprofit organization Vineyard Team.

“Overall, we are being super-thoughtful about how we’re farming, and limiting inputs to the bare minimum,” said owner Andy Niner. Nonetheless, the certification still meant extra work.

Like most robust certifications, the SIP program requires continued and comprehensive documentation. “They look at the chemicals you use and how much you apply, your water use and how you measure it, how you treat your people, a whole host of things. And then they audit every year and stamp that you are actually doing what you say you’re doing,” he said.

That documentation turned out to be a good thing in terms of tracking the details of farm operations, Niner said. In fact, the vineyard intends to beef up its internal reporting as a way to improve efficiencies. “There are a million examples of that in a complex business like farming and winemaking, whether it’s related to soil health, water use or energy use,” he said. “We want to improve our metrics on all of it so we can react quickly when we flip out of balance.”

Niner said he plans to stick with the program he’s in and hasn’t looked into the newer ROC in much detail.

Is certification worth it?

Lonborg, Brinkley and Niner are all glad they sought the certifications and include the ROC or SIP logo on their bottles of wine. Whether those logos translate to increased wine sales, however, is still unclear.

“I think people respect a quality approach, so if you add family-owned, sustainability and better wine together, they may buy a more expensive bottle of wine, but there’s too much noise there to say they’re paying more for sustainability only,” Niner said.

The new ROC stamp may not yet be generating more sales, but it is drawing more interest, Lonborg said. “It is definitely being talked about a lot more, and it has started to reach crowds that we probably weren’t reaching beforehand.” That includes “a younger generation of wine drinkers, people who are focused on the environment to a certain extent, and who do care how their products are made.”

The hope is that the interest in certifications grows among consumers and producers, and the trend toward lower-input agriculture builds, Brinkley said. That’s already happening here and there.

“Some markets have never even heard of regenerative certification, while in some places it’s a huge buzz,” he said. For example, a New York wine shop owner with a young clientele told him: “The first thing (customers) do is turn the bottle to the back to see if there’s a stamp.”

—by Leslie Mertz

Leave A Comment