—story by Ross Courtney

—photos by Ross Courtney and TJ Mullinax

Leaf removal and net retraction both work to boost color in apples.

Those are the conclusions made by Lee Kalcsits of Washington State University, endowed chair of environmental physiology for tree fruit. Kalcsits recently completed two separate, four-year studies of both techniques and reported they each offer similar benefits.

Both netting and leaves shade apples during the hottest part of the summer, protecting them from sunburn. Removing either — by blowing off leaves or pulling back the netting — removes the barrier and allows sunlight to penetrate the canopy and color the fruit.

Higher fruit color bumps up profits, so netting could add up to $5,000 per acre in returns, assuming a $56 box price and 60 bins per acre, according to Kalcsits’ math.

What’s more, both have similar timings, the research determined.

“They both work to open up the canopy to increased light … and whether treatments were applied at seven or 14 days before harvest, the positive effect on red color was apparent,” he said.

The two projects, led by master’s degree students Noah Willsea and Orlando Howe, were funded for four years at roughly $256,000, combined, by the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission. The researchers plan to submit detailed reports of their findings to scientific journals this winter.

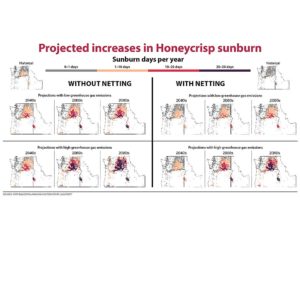

Kalcsits generally advises growers to “stack” sunburn mitigation strategies — netting, fogging and canopy management — because one is not enough anymore. Summers can be just too hot in arid Eastern Washington.

“Netting can have limited effectiveness if temperatures exceed 105, so fogging is important if the grower wants to limit all sunburn from happening for cultivars they grow which are susceptible,” he said.

Among Kalcsits’ other key results:

—Removing just 25 percent of the leaves offered benefits. Unsurprisingly, leaf removal above 75 percent increased sunburn damage. Removing half the leaf cover reduced return bloom and yields but did not affect vigor.

—Deleafing had little effect on carbohydrate content in storage tissues.

—Netting offers more sunburn protection than evaporative cooling, which reduced severe sunburn when used in conjunction with netting but didn’t help much on its own during the infamous heat dome in June 2021, when record-high temperatures scorched the Pacific Northwest for a week.

Kalcsits may continue some of his netting and defoliation research with partners in other regions of the United States under a new $6.75 million grant to study climate mitigation for pome fruit, funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture Specialty Crop Research Initiative.

“We are proposing further coordinated deleafing experiments in different regions of the U.S. and also will continue with applied trials on protective netting for reducing sunburn and increasing fruit quality,” he said.

Commercial application

Applying the results to commercial orchards will be up to individual growers, Kalcsits said.

Things can get complicated. “There are just so many things to consider,” said Matt Jeffery, vice president of orchards for McDougall and Sons of Wenatchee. The company collaborated on Kalcsits’ leaf removal trials and was among the first Washington growers to adopt curtain-style retractable netting.

However, McDougall and Sons has not installed new netting since 2019. The company finds fogging less expensive to install and deploy. Fogging is mostly used for sunburn protection, but it can help color-development at the right time of year, Jeffery said.

The company uses defoliators each fall, though, maintaining a fleet of about 10 Fruit Tec REDpulse and Collard machines. Timing is a logistical challenge, Jeffery said. Managers operate the machines once they’re certain summer heat has passed, aiming for roughly three weeks before harvest.

“Really, as early as we can, as long as we can anticipate no major heat events on the horizon,” he said.

They don’t always meet their targets, especially with Washington’s overtime threshold at 40 hours, Jeffery said.

They defoliate Cripps Pink, Ambrosia and Envy, varieties that come off trees later in the fall.

They don’t try Galas because the weather is usually too hot at the time of harvest. They don’t defoliate Honeycrisp because the fruit is too susceptible to drop and limb injury. They don’t do WA 38 because the apple colors well enough without help.

“You can almost get color in the dark with those things,” Jeffery said. Kalcsits found the same thing with WA 38 in some of his trials.

McDougall and Sons also stretches reflective fabric to boost color, once they are confident the heat waves have passed. They’ve been burned on that one though, having to turn on overhead cooling after laying fabric.

Even before the project was finished, Chelan Fruit put the netting trial results to use at Monument Hills Orchard near Quincy, where Kalcsits ran some of his trials, said Garrett Grubbs, company orchard director at the time.

Growers often assumed they needed to expose apples much longer, increasing their risk of sunburn, hail damage or other hazards, Grubbs said.

“You get so much benefit from that seven days,” Grubbs said.

That’s extra important for an orchard like Monument Hills, which has nonretractable netting. Once crews roll it up for the fall, “it ain’t going back,” Grubbs said.

That orchard is now owned by International Farming and managed by AgriMACS.

Grubbs now works as a winemaker and operates his family’s 100-acre orchard near Entiat. He doesn’t have netting, but he has applied the same lessons to reflective fabric. He deploys it much closer to harvest, reducing the risk of sunburn and giving crews time to drive through the rows for final fungicide applications.

He found the results applicable right away.

“It’s usable,” he said. “You don’t have to wait 10 years.” •

Climate mitigation study receives funding

Washington State University received a $6.75 million grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture Specialty Crop Research Initiative to study climate mitigation in apple and pear orchards.

With the funding, Lee Kalcsits, associate professor and endowed chair of environmental physiology for tree fruit, will lead a team of 21 scientists from seven institutions on a four-year project exploring cold hardiness for new cultivars, mitigating sunburn and enhancing red color, among other anticipated research topics.

Kalcsits said the project will give researchers from different parts of the nation a chance to share expertise. For example, growers in Washington’s arid regions contend more with heat but have recently experienced cold losses. In the Eastern U.S., cold risk is higher, but climatologists predict growers there will face extreme heat more often in the future.

Developing models for growers to more reliably assess risk is among their goals, as is a historic study of extreme temperature impacts and cost/benefit comparisons of mitigation strategies.

Joining WSU in the project are Cornell University, University of Maine, Michigan State University, Penn State University, Oregon State University and the USDA Agricultural Research Service.

—R. Courtney

Leave A Comment