In Southern Oregon’s temperate Rogue Valley, where high-quality pear production has long dominated the agricultural landscape, wine grapes now occupy a significant share of the land and the research and extension efforts in the region.

Situated between Northern California’s Cabernet-heavy production region and Northern Oregon’s primary Pinot Noir production in the Willamette Valley, Southern Oregon has emerged as the fastest-growing wine production region in the state. Between 2002 and 2017, wine grape acreage in the Rogue Valley, covering Jackson and Josephine counties, increased 110 percent, while pear acreage decreased 43 percent.

Research in the 1960s by Rogue Valley wine industry pioneer and Oregon State University pomologist Porter Lombard provided the foundation for the now flourishing wine industry.

Today, at the Southern Oregon Research and Extension Center, located near Medford, viticulturist Alexander Levin and plant pathologist Achala KC have brought a renewed focus to the region’s wine grape production. Both came to the center in 2016 and have launched research programs targeting grapevine red blotch, rootstocks and irrigation, along with continuing work on the diseases facing the region’s remaining pear producers.

Wine grape research

The research center includes 20 acres of orchards and two new vineyards: one planted in 2017 with Pinot Noir and Chardonnay and one planted this year with Pinot Noir and Cabernet Sauvignon on 10 different rootstocks.

Pinot Noir in the Medford region is an early-ripening variety, and Cabernet is very late. Levin chose the varieties not only because they’re economically important but because they are bookends of the ripening window.

“People try to use rootstocks to advance or delay ripening,” Levin said. “So, I’m wondering … if this is true, how true is it? Can you really push or delay the ripening of these varieties?”

With 20 different variety and rootstock combinations, the newest vineyard also has four different irrigation regimes set up, allowing each of the combinations to be irrigated four different ways. The research builds on his work as a graduate student, where he studied the differences in drought response among red grape cultivars at the University of California, Davis.

“We’re curious about how you can manage irrigation based on rootstock,” he said. “It’s a challenge to manage some and it’s a little easier to manage others. The question is: How are those differences characterized and what’s going on underground?” Levin hopes to answer questions about water and nutrient uptake as well.

In the 3-year-old research vineyard, they are conducting pest and disease research, including fungicide trials for control of powdery mildew and research on grapevine red blotch virus.

Levin and KC are part of a red blotch research team led by UC Davis and funded by a U.S. Department of Agriculture Specialty Crop Research Initiative grant. They have completed two years of research and are funded for a third.

Until key questions about red blotch vectors and disease management can be answered, their work focuses on cultural management and alternatives for growers unable or unwilling to heed the current recommendation to replace vineyards infected with red blotch.

Levin’s research aims to determine whether or not some of the negative effects of the virus can be improved or mitigated by changing the typical practice of deficit irrigation.

“In a situation where you have diseased vines, and the quality is compromised due to the disease, our hypothesis is, actually, you’re going to be making it worse by imposing some sort of stress, like water stress,” Levin said. “And our preliminary results show that it is; it actually does make it worse.”

KC’s research is focused on the disease management aspect of red blotch.

“What we found last year was when we have more water, the severity seemed to decrease,” she said. But more irrigation may simply mean more green foliage and fewer red blotch leaves.

“We saw that effect but is it really a positive effect on the vine or is it just because we see more green leaves?” she said. She will continue to investigate and hopes to determine whether having more green leaves one year will affect the following year’s crop. “That carry-over effect will be interesting to see,” she said.

Pears remain a focus

KC, who holds a master’s and a doctorate degree in plant pathology from North Dakota State University and conducted postdoctoral research on pomegranate diseases in Florida, also studies pear pathogens. She picked up some of the research projects started by OSU plant pathologist David Sugar, who retired in 2014.

Sugar’s work focused primarily on postharvest disorders in the area’s pear crops — predominantly Comice, Bosc and Bartlett — and he identified at least nine different fungal pathogens that can cause postharvest rots.

Recognizing some gaps between Sugar’s work and her own, KC wanted to know if there were any differences in the pathogen population, so she started sampling. She did find some new pathogens, and she determined some of those pathogens were related to wine grape diseases.

“It’s an interesting story,” she said — finding possible pathogens from wine grapes that can cause pear postharvest rot.

KC said the incidence is not widespread and the pathogens were mostly seen on the preharvest side. “When we were collecting samples on the trees, we would see more of those pathogens, but as we go late in the season they seem to disappear,” she said. “Whatever fungicides we are working with are probably taking care of those pathogens already.”

In her research on cross-crop pathogens, KC is studying Botrytis cinerea, which causes botrytis bunch rot in grapes and gray mold or storage rot in pears. It’s currently unclear whether there is a relation between grape bunch rot and pear gray mold.

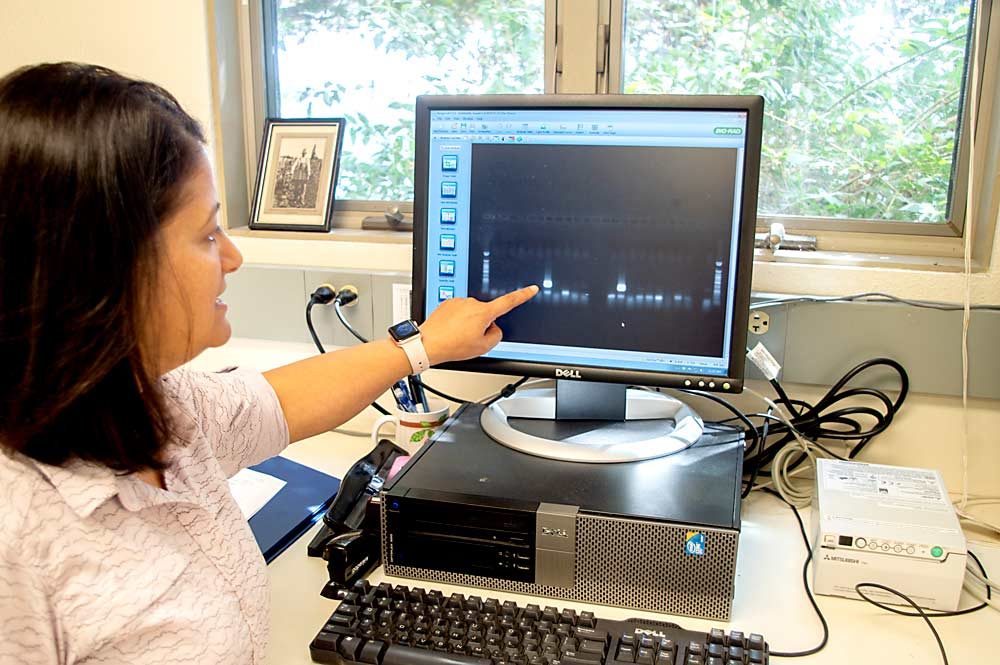

“Even though those are the same pathogen, we don’t know if they are related, or if they are the same, or if the pathogens from grape infect pear or if pear infects grape,” she said. Her laboratory staff uses both traditional culture isolations and DNA extraction technology to try to answer those questions.

She also plans to continue monitoring to see if the new grape pathogens pose a significant problem for pears.

“With new crops, there are always possibilities of introducing new pathogens,” KC said.

The new neighbor

While wine grapes are a relatively new crop in Southern Oregon, the newest is hemp.

According to an article in the Medford-based Mail Tribune, citing statistics from the Oregon Department of Agriculture, Jackson County is the leading hemp producer and now has approximately 8,600 acres planted in hemp, outdistancing the combined 6,600 acres of wine grapes and pears.

“We don’t know how many years it will be before we start seeing some big issues with diseases and pests — for the same crop but also for other crops,” KC said. In the rush to plant a booming new crop, diseases can flourish as well if certified clean plants are not a priority. That’s the story behind grapevine red blotch, she said.

“The way red blotch became so problematic was because of the huge commercialization of new planting everywhere,” she said. At that time, red blotch was not an identified issue and the nurseries were not testing for it, so infected planting material was widely propagated and planted before the concerns were recognized.

Agriculture in the region is changing, and so are the research and extension needs for the team at the Medford facility. Levin and KC also collaborate with OSU entomologist Rick Hilton, who is also stationed at the center.

“We all work very closely together and that’s really nice to have that sort of team here,” Levin said. “As an experiment station, we’re out on the frontier and it’s nice to have some colleagues to work on things together.” •

—by Jonelle Mejica

Leave A Comment