One of the best management strategies wine grape growers have to manage vines infected with grapevine leafroll disease is to rogue them out of the vineyard, but growers face an unknown question: What is the economic cost to this strategy over the long term?

Trent Ball, agriculture department chair at Yakima Valley College, aimed to answer that question by examining the on-farm costs of vine removal, factoring in the rate of spread, compared with a do-nothing approach, and the resulting impacts to grape and wine yield and quality.

Then, Ball compared these costs over time. “It’s not just what it would cost me next year. This roguing strategy is something you would do over time, that’s perpetual,” he said at the Washington Winegrowers conference in February. For that reason, Ball said, the study examined the cost on an annual basis over a period of 20 years.

The questions

If one of the best management strategies is to rogue infected vines, is it financially viable over the long term?

Recent research by Washington State University plant pathologist Naidu Rayapati, director of WSU’s Irrigated Agriculture Research and Extension Center, has shown grapevine leafroll disease can spread very quickly, infecting more than 50 percent of a Washington vineyard in just a couple of years, or slowly over time. Management practices vary depending on the rate of spread at a specific site.

Yields also fall on average by about 20 percent for leafroll-infected vines. However, grapes also could see a Brix reduction. “The quality implications can be significant as well,” Ball said. “Based on your contract with your buyer, you may have a Brix minimum — 23.5 on red is typical — and there can be a penalty for any Brix below that.”

Generally, growers should be scouting for disease in the fall, identifying those vines that look infected and testing and removing those infected vines in the winter.

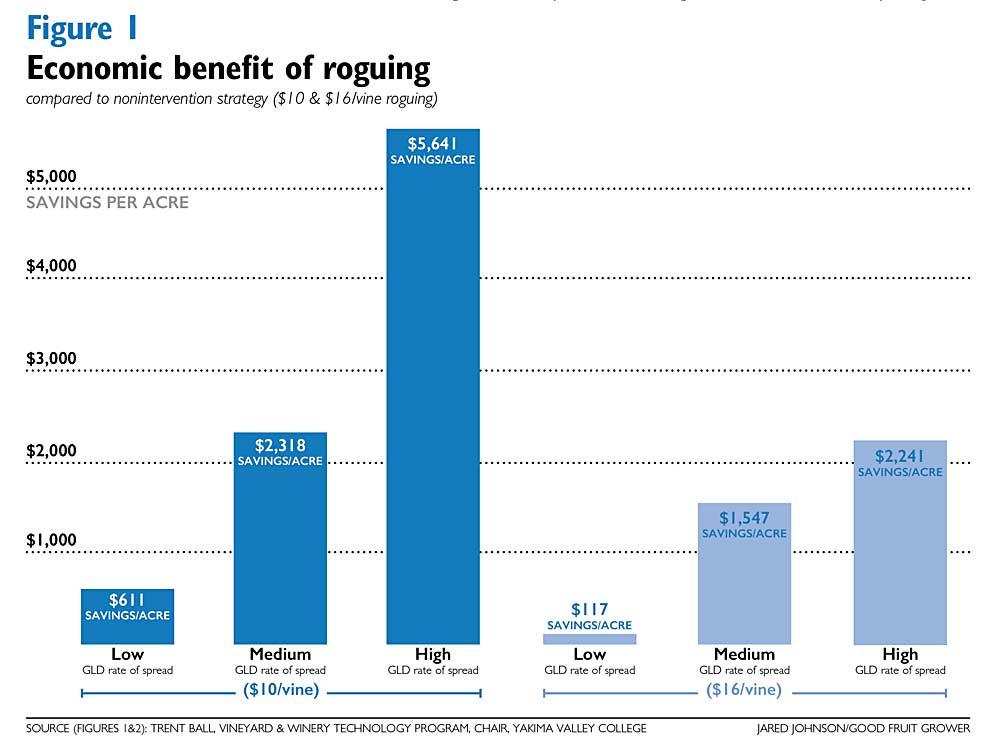

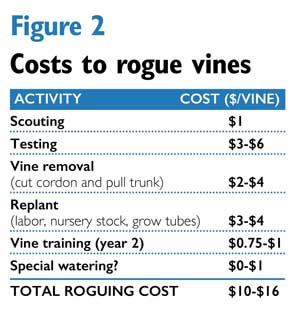

For Ball’s analysis, roguing costs ranged from $10 to $16 per vine. Included in those figures were the costs for scouting and testing for disease, vine removal, replanting followed by vine training in year two, and special irrigation that might be required to accommodate a young, new vine in an older vineyard (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Economic benefit of roguing, compared to nonintervention strategy. (Source: Trent Ball/Yakima Valley College. Graphic: Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower)

Ball also looked at those costs, $10 or $16 per acre, at low, medium and high rates of spread. (A low rate assumed a grower removed six vines per year, with nine vines per year at a medium rate of spread and an aggressive 40 vines per year at a high rate of spread.)

Overall, growers see an economic benefit to vine removal regardless of the rate of spread and regardless of whether the vine removal cost was estimated at $10 or $16 per vine. The economic savings were highest at the lower $10 per vine removal cost, increasing with the rate of infection (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Costs to rogue vines. (Source: Trent Ball/Yakima Valley College. Graphic: Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower)

“As you would expect, if it costs more to rogue, it’s more impactful and hurts your bottom line a little bit, but it’s more beneficial than not doing anything,” he said. “Not doing anything is going to cost you more from an economic perspective.”

And if a winery imposes a 1 percent price reduction for low Brix?

The addition of a Brix penalty really doesn’t factor into the equation until a grower has a high rate of infection. At that point, a grower could save $13,000 per acre compared to the do-nothing approach to the disease, at the $10 per vine cost to remove vines.

So, at what point is the cost of roguing higher than the benefit a grower would see from reducing the virus impact?

At just a 20 percent yield reduction from a low spread rate, with a roguing cost of $20 per vine, roguing was not cost beneficial. “Over 20, 25 years, if you’re only going to end up with a rate of 20 percent infection, then it wasn’t economically viable to spend $20 per vine to rogue and replace,” Ball said.

However, at the 15 percent yield reduction level — and some varieties don’t show as much of a yield impact from the disease — then within the $10 to $14 per vine cost range, growers can view roguing as a viable option to handle the costs and still maintain an economic advantage.

At around $30 per vine for roguing, “it’s almost not viable at all,” he said.

One other thing: If your operation is infected, at what point is roguing no longer an effective strategy?

At the 40 percent infection level, growers should just replant, Ball said. “Keep the bulk of the trellis system, pull vines, replant with certified material, use grow tubes,” he said. “At the 40 percent threshold, the roguing strategy becomes too expensive and you can’t justify the additional cost.”

Ball’s take-home messages:

—Grapevine leafroll disease can occur in a vineyard regardless of whether a grower does everything right — but growers can reduce their risk by using certified material and employing good management practices, controlling for insects and roguing where necessary.

—Addressing grapevine leafroll disease at an early stage provides the highest economic benefit through roguing.

—Vineyard replacement should be exercised when infection levels top 40 percent.

In addition, “the higher your fruit value, the more effective it is for roguing,” Ball said. “When the fruit value is lower, it’s not always as effective.”

Ultimately, the decision will depend on the rate of infection spread, the value of the fruit and a grower’s risk tolerance. •

—by Shannon Dininny

This research was funded by a Washington State Department of Agriculture Specialty Crop Block Grant, in cooperation with research by WSU’s Irrigated Agriculture Research and Extension Center.

Leave A Comment