Researcher Long He, top, manipulates Washington State University’s prototype of a three-tiered apple harvester into place while graduate student Xin Zhang stands ready with the bags during trials in October 2017 in a commercial Jazz block near Prosser, Washington. With certain varieties, WSU researchers have used the machine to harvest about 90 percent of the fruit on a tree. He, a biological system engineer, has since joined Pennsylvania State University. (Ross Courtney/Good Fruit Grower)

Researchers still have a long way to go developing a shake-and-catch apple harvester, but they have discovered at least one thing: variety matters.

For some varieties, it is showing a lot of promise, said Manoj Karkee, the lead investigator for the project at Washington State University’s Center for Precision and Automated Agriculture Systems in Prosser.

Take Jazz.

The stems of Jazz apples, a club variety from New Zealand, came loose from their branches when shaken by the prototype, tested the past three years in a block near Prosser.

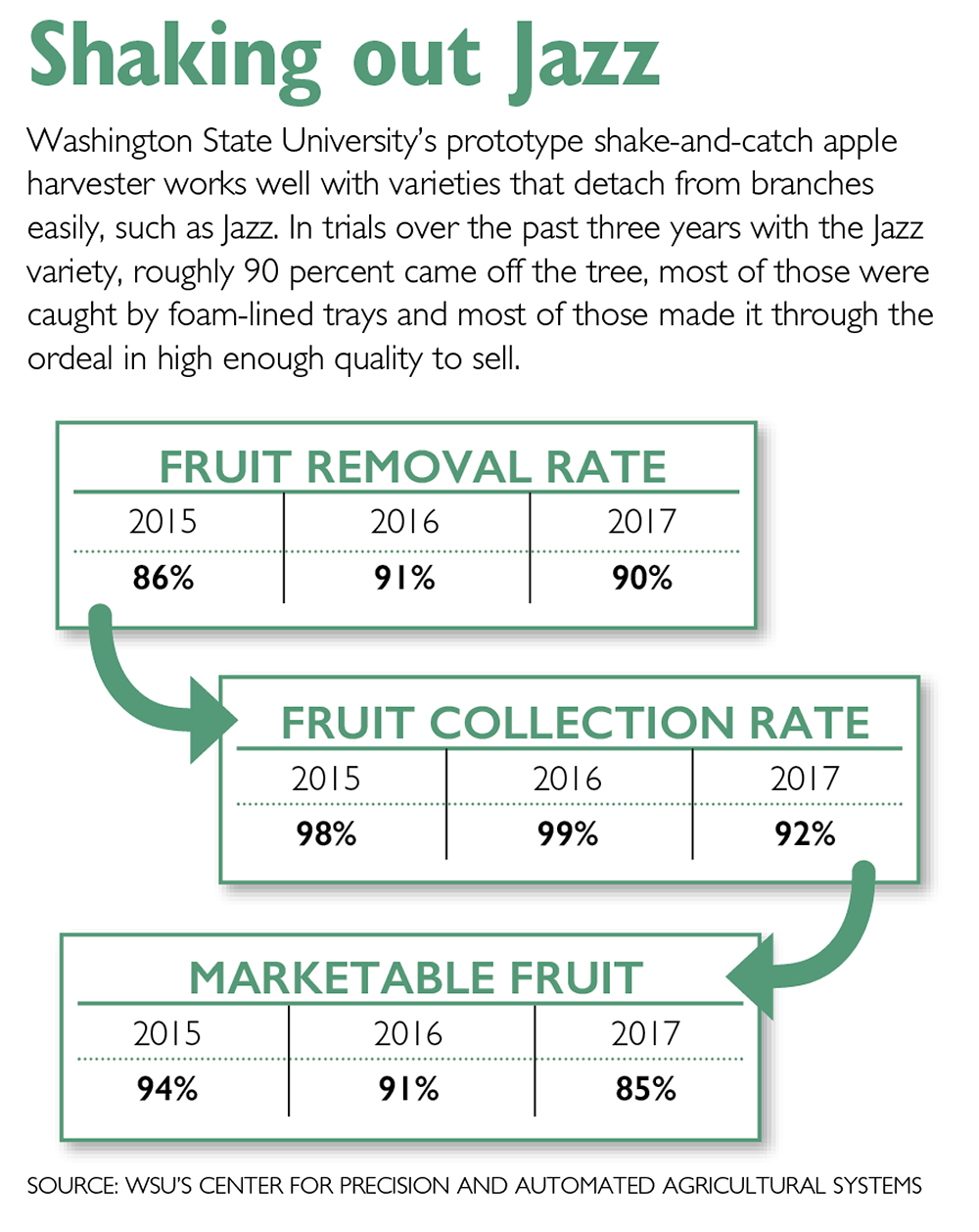

Washington State University’s prototype shake-and-catch apple harvester works well with varieties that detach from branches easily, such as Jazz. In trials over the past three years with the Jazz variety, roughly 90 percent came off the tree, most of those were caught by foam-lined trays and most of those made it through the ordeal in high enough quality to sell. (Source: WSU’s Center for Precision and Automated Agricultural Systems. Graphic by Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower)

Roughly, nine out of every 10 apples on the branches detached. Of those, almost all of them landed safely in the machine’s tiered, padded catch trays as opposed to the ground. And of those, most made it through the ordeal bruise-free and marketable.

The results aren’t as good as hand picking, which growers say causes only between 3 percent and 6 percent waste, but the machine is getting close.

“Ten percent is where farmers start to be interested,” Karkee said.

Gala, not so much. Galas grow toward the end of longer branches and require more shaking to get them to detach. The harder the machine shakes, the farther the apples fly and the more they bruise or miss the trays completely.

“The major reason is the fruit retention force is different among varieties,” said Long He, a biological systems engineer who recently moved from WSU-Prosser to Pennsylvania State University. “With a small fruit retention force, the fruit could be removed easier, while those that have high force, it is hard to remove, as well as they may break the spur or twig.” He spent three years with the project.

The duct-tape padded mechanical shaker arm grips and agitates horizontal branches until apples fall off. (Ross Courtney/Good Fruit Grower)

The machine features two sides, each with three adjustable foam-lined catch trays that butt against each side of the tree row.

A mechanical arm on one side reaches out to shake a limb until the apples fall onto the trays. It’s designed to work with a two-dimensional fruit wall with fruit hanging from lateral branches trained to a trellis wire.

So far, the contraption moves slowly. The researchers and assistants use wrenches to adjust the tray and shaker arm at each stop.

But other investigators at the center have been working to automate the process with interpretive cameras and software to recognize apples, trees and branches. The team plans to begin incorporating those components with the shaker in more trials this fall.

That should speed things up, Karkee said. Eventually, the whole apparatus will operate by itself while a farmer watches on video screens from an office.

That’s the idea, anyway.

“I’m confident that speed will not be a challenge,” he said.

Early work was funded by the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission with a $53,000 grant. Since then, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the university itself have funded experiments. This year, the project is part of a larger $3 million proposal with the University of California, Davis.

The researchers and their technicians adjust the foam-lined catch plates, three on each side of the row, to allow the shaken apples to fall only a few inches and thus protect them from bruising. (Ross Courtney/Good Fruit Grower)

The race for automation

The tiered harvester is just another step toward the mechanization necessary for society to feed itself in the future, said Dave Allan, retired orchard manager for Allan Bros. in Naches, Washington. The tight labor market is only going to get tighter with an aging population.

“We’re going to have to automate,” said Allan, a longtime member of the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission known for collaborating with technology efforts.

The shake-and-catch model has limits, he said. So far, it hasn’t worked well on apples that tend to grow at the end of branches or long darts because it takes too much shaking motion to drop them. Unfortunately, the Cosmic Crisp, WSU’s new variety, is in that category.

Still, the prototype has promise and Allan hopes research continues.

“I don’t think we should abandon the shake-and-catch concept,” he said.

Indeed, automation is the holy grail and the race is on. Abundant Robotics of California, backed by investment money from GV, formerly Google Ventures, is still testing a vacuum picker, while FF Robotics of Israel is working on a hand-style gripper.

WSU researchers don’t intend to replace those with shake-and-catch. There’s room for more than one method, Karkee said.

He envisions the shake-and-catch concept handling mass harvests with certain varieties, while the vacuum and gripper models may be more precise for higher-value varieties that don’t fall as easily, such as Honeycrisp.

“In my opinion, they will exist together,” he said.

In fact, shake-and-catch might make a perfect fit for cider apples.

In 2016, the WSU team ran a trial in a block of Harry Master Jersey, a cider specific variety. It removed apples at roughly the same rate as Jazz. The researchers did not measure the catch rate or marketability rate because the trees lacked the lateral architecture needed.

Tieton Cider Works in Tieton, Washington, still picks apples by hand, though in other parts of the world, growers shake the trees by the trunk, let the apples fall to the ground and then scoop them up. That works if you process them right away, said General Manager Marcus Robert.

Cider apples can tolerate some bruising; they will be pressed anyway. Too much bruising, however, and they won’t store as long, forcing the grower to process them quickly. That’s not always possible, Robert said.

Shake-and-catch might give an in-between option, he said. “It’s about getting those apples off the tree with the lowest inputs.”

The shaker arm reaches for a branch of ripe fruit. The ultimate goal is to automate the shaker with apple, tree and branch recognition vision software, but the prototype’s capabilities are limited during test stages. (Ross Courtney/Good Fruit Grower)

Agricultural engineer Mark De Kline first worked on shake-and-catch as part of his engineering dissertation years ago at WSU-Prosser. He even experimented with attaching a hook to a reciprocating saw and projected he could harvest 20,000 apples per hour that way.

To him, shake-and-catch helps fills the industry’s huge gap between pure hand labor and full automation. He never envisioned the technology for selective picking, like the robotic machines intend to do. “It was all geared for bulk harvesting.”

He also sees the two working together. “You don’t use a Phillips for a flathead, but if you’re going to build a machine you’re going to need both.” •

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment