Denny Hayden planted these Coral Champagne cherries at an 18 inch spacing to test out dwarfing rootstocks developed by Michigan State University. With about 100 trees on the new rootstocks, he’s one of about a dozen Northwest growers to plant experiments to learn more about how to grow cherries on the new rootstocks and the high density systems they allow. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

Did someone say dwarfing?

Pollinizers tower over about 100 skinny second-leaf Coral Champagne cherry trees planted on precocious, dwarfing rootstocks.

Grower Denny Hayden planted the trees at an 18-inch spacing and plans to train them to a narrow V-trellis to test the possibility that these new rootstocks, developed by Michigan State University, could create a pedestrian cherry orchard.

“If we could grow these things like apples on a Malling 9 or smaller, that would be great,” he said. But, it’s still very much of an experiment to see how the trees, planted in equal number on rootstocks Cass, Clare, Clinton, Crawford and Lake, will perform.

Hayden is pleased to see that most of the trees, which were in weak shape last season, survived their first winter in his Pasco, Washington, orchard, but he’s hesitant about the density.

“I think this is pushing the envelope on tightness,” he said of the 18-inch spacing, which was recommended by Washington State University horticulturist Stefano Musacchi. Still, it’s exciting to finally have a chance to try out these rootstocks, Hayden said, since Northwest cherry growers have supported their development for years.

Crawford is one of the five rootstocks that Michigan State University has patented and released, with a volume restriction, under the trade name Corette. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

Releasing the rootstocks

Any grower who wants to test these new rootstocks and the high-density systems they make possible now can, thanks to MSU’s decision late last year to patent and release the series, trademarked as Corette, to nurseries. But the release comes with an unusual volume restriction: No grower can buy more than 1,000 of each rootstock.

“Basically, when you patent something, people think you are endorsing it,” said Amy Iezzoni, the MSU breeder who developed the rootstocks. Admittedly, she’s not ready to endorse them yet because there are too many unknowns about the ideal density, training, scion pairing and soil compatibility for these rootstocks to succeed.

“In sweet cherry and tart cherry, when you are looking at the MSU rootstocks, you are really talking about changing the production system,” she said. “The only way we are going to figure out if these are going to be commercially useful is to have growers try them, but try them in such a way that they are not taking a big risk, because there are a lot of unknowns.”

That restriction effectively signals to growers that “we don’t know enough about how to farm these, but I recognize that you need to practice,” said Dale Goldy, horticulturist for Washington’s Stemilt Ag Services.

He hopes MSU’s approach will prevent cherry growers from suffering some of the growing pains and spectacular failures that the apple industry endured during the initial adoption of dwarfing rootstocks and high-density systems.

“It’s such a radical change from growing cherries on Mazzard rootstocks to these dwarfing rootstocks,” he said. “For me, it’s more about trying to figure out how to do SSA.”

The SSA system, which stands for super slender axe, is a very high-density, semi-pedestrian system of single-leader dwarfing trees that aims to produce fruit at the base of 1-year-old branches.

“The idea that we can plant cherries at densities similar to what apples can grow at and produce high-quality, high-sugar, high-density fruit is a significant change in process. The learning that goes with that and the number of people that need to learn that is really significant,” Goldy said.

Michigan State University researcher and tree fruit breeder, Amy Iezzoni, visits one of her cherry dwarfing rootstock trials growing in Central Washington orchards on April 15, 2016. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

Free to experiment

Just shy of a dozen growers in the Pacific Northwest have already planted small test plots with the new rootstocks, Iezzoni said. The rootstocks are now available to tart cherry growers as well, but none that she knows of have taken the leap except for the grower participating in MSU’s over-the-row harvester trials. (See “The art of tart,” Good Fruit Grower, May 15, 2018 issue).

Releasing the rootstocks to nurseries for commercial production, as opposed to the small-scale propagation done for experiments, means the quality of the trees available to growers should improve, Iezzoni said. Unlike a controlled rootstock trial, Iezzoni and her collaborators are not telling Northwest growers how to plant or grow trees on these rootstocks or what data to collect.

“It’s pretty much we’re learning with them,” said Bernardita Sallato, Washington State University Extension educator and a collaborator on the rootstock research. “The only advice I give them is that whatever they do, they do the same for all the rootstocks, so we can see the differences and know that it is from the rootstocks, not the management.”

This uncontrolled experiment may seem a bit unorthodox, but the rootstocks have already spent several years in controlled trials in Mattawa and Wenatchee, Washington, and The Dalles, Oregon, where the results, although preliminary, are promising.

Trees are consistently smaller than controls on Krymsk 5 and 6 and Gisela 5 and 6, and Iezzoni expects this upcoming harvest, the second for most of the trial, to offer valuable fruit size and quality data.

Releasing the rootstocks to growers, in limited quantities, gives a wider range of options and more real-world conditions to see how they perform.

“The soils, the water management, the water quality, it will all vary a lot in terms of how these trees react,” Sallato said, adding that the dwarfing root systems often have less tolerance to stresses than larger rootstocks.

“You can’t afford to evaluate a breeding program in too many locations. I think this is the best way to go, the growers take the reins and the growers, they are the best to judge.”

Last year, Zirkle Fruit planted about 400 Sweetheart, Regina and Benton trees on the MSU rootstocks, Mattawa area manager Aran Urlacher said.

The Sweethearts and Reginas are part of Iezzoni’s ongoing trials, but Zirkle decided to plant the Bentons as its own experiment within a larger planting of Benton on Gi5.

“Benton’s strong on Gi5, so it may really benefit from a more dwarfing rootstock,” Urlacher said. The MSU trees are planted at two-foot spacing, and he plans to train them to a V-trellis with a modified SSA production system. The rest of the block will be in the same trellis but using a bi-axis to help control the vigor.

The trees on MSU rootstocks — 1-year-old whips of Sweetheart and Regina, with Benton as sleeping eyes — all had a slow start last year, Urlacher said. But he’s hoping that the precocious rootstocks will prove themselves by putting blocks into production earlier. And for Sweethearts, which tend to overset, he’s hoping the SSA system can better control crop load.

“We’re hoping to have our cake and eat it too by setting just the base of the 1-year-old wood. Then we get our Sweetheart tonnage and get away from hand thinning,” Urlacher said. “It sounds good, in theory. But we don’t know what we don’t know yet.”

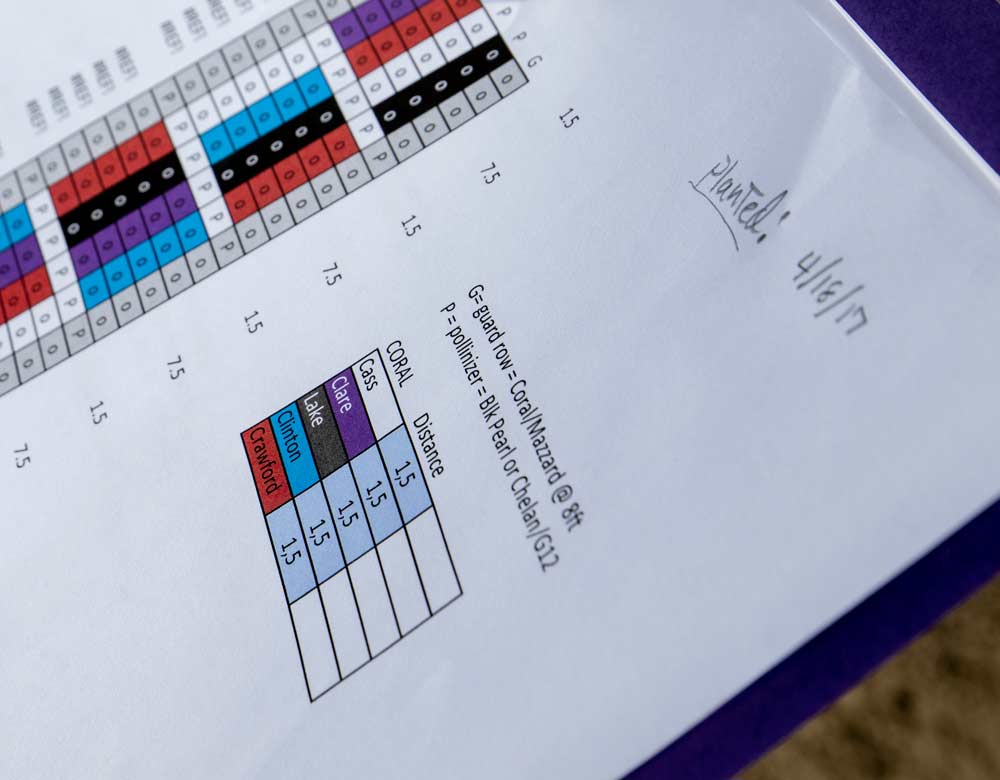

Cherry grower Denny Hayden shows the experimental design for his planting of about 100 trees on five different dwarfing rootstocks. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

Hayden took a similar approach. He planted the trial in the midst of a larger block of Coral Champagne cherries on Mazzard rootstocks, which he plans to grow with two leaders on a V-trellis.

The dwarfing trees will grow on a narrow V-trellis as well but with just one leader each. They lagged behind the rest of the planting significantly this spring, but recent scoring and Promalin (gibberellic acid and benzyladenine) treatment should get them branching, Hayden said.

He plans to manage the dwarfing trees the same as those on Mazzard, as far as irrigation and nutrition schedules go, but he did skip the herbicide in the trial plot this spring to protect the extra-small, second-leaf trees.

Several years ago, Goldy planted the MSU rootstocks with Skeenas, which have shown difficulty branching enough for the SSA system. That’s just one of the many things he’s learned through trial and error, and he expects it will take growers four or five years of practice before they are ready to plant on these new rootstocks at a commercial scale.

“We have to be able to uncover the things we didn’t know we needed to know,” Goldy said, adding that he’s done several SSA trials so far. “Each time we do this, we get a lot closer.” •

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment