A single handful of good orchard soil is teeming with about 7.5 billion microbes, including some 6 billion bacteria that are busy releasing minerals and other elements essential for healthy trees.

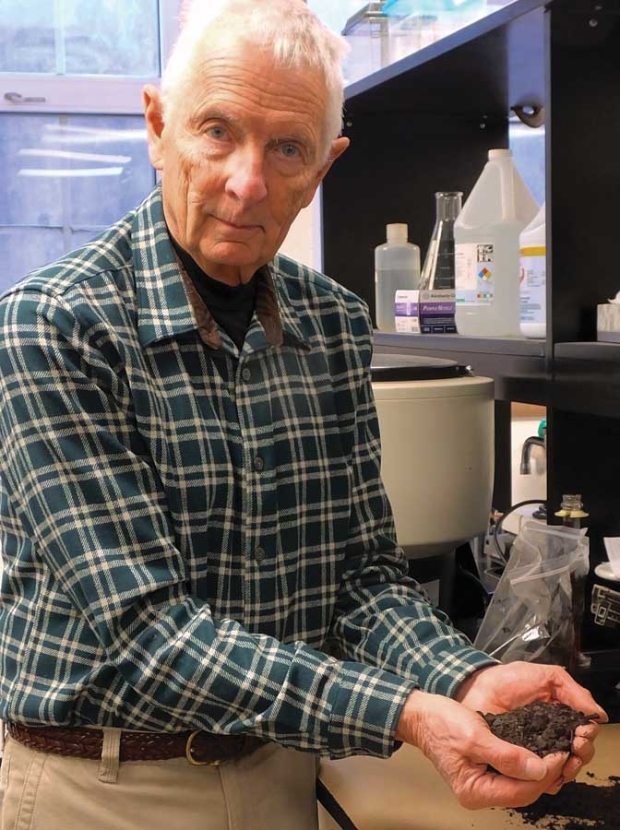

George Bird, Michigan State University professor and researcher, holds a handful of soil, which teems with bacteria and other microbes. He urges growers to use newer soil tests, which include data on microbes and other previously neglected aspects of soil health that are critical for productive orchards and vineyards. (Leslie Mertz/for Good Fruit Grower)

However, soil science for the past 50 years has mostly neglected this dynamic biological component. Instead, the science has taken primarily a chemical- and physical-driven approach with tests designed to determine the need for various fertilizers and how much to apply, said Dr. George Bird, who has spent years studying soil quality as a professor and researcher in Michigan State University’s entomology department.

Recent soil tests, such as those that Cornell University, Haney (U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Research Service, or USDA-ARS) and Solvita have rolled out over the past few years, have begun to report these key biological parameters, but growers have yet to embrace the new tests, and those who have are struggling to understand what the test results mean, he said.

“Soil health is a new concept, and encompasses indicators that grape growers and tree fruit growers are often not familiar with, but it is something I feel very strongly that they’ll all be using within the next decade,” Bird said.

Soil testing changes

One of the parameters recently added to the new tests is active carbon potential. Carbon bonds to most of the minerals essential to plants and their fruits, and a soil’s active carbon potential is a measure of how readily carbon releases those minerals for uptake by plants.

Active carbon potentials differ from one soil to the next, and therefore can have different effects on the growth and development of plants, including vines and trees. “That means that active carbon is very important in relation to the health of orchard soil,” Bird said.

Another vital component of soil health is nitrogen utilization. “Soil is a very nitrogen-deficient environment, but you need nitrogen for growth and development of plants, because it’s a significant component of nucleic acids, such as DNA, and proteins,” he explained.

That’s where bacteria and other microbes come in. They convert two forms of otherwise unusable nitrogen into types of the chemical element that plants can exploit.

One form is atmospheric nitrogen, which bacteria convert through the process of nitrogen fixation, and the other is the nitrogen in soil organic matter, which bacteria, fungi, nematodes and other organisms convert through the processes of nitrogen mineralization and nitrification.

“With some 6 billion bacteria in every handful of soil, bacteria are nitrogen-rich organisms,” he said.

Soil tests may report nitrogen utilization data as “nitrogen mineralization potential” or as “micrograms of nitrogen per gram of dry weight of soil per week” depending on the soil test used, he said. “This information is something that you have not gotten back in the past four or five decades in a regular soil analysis, but it is a very important factor in soil health.”

If he had to pick just one parameter to measure for soil health, Bird said it would be water-stable aggregates.

“I like the water-stable-aggregates category because it integrates three things: the physical parameters of the soil, or the mineral matter; the biology, or the bacteria, fungi, and other microbes; and the chemicals that the microbes produce and that get those mineral particles to stick together and form a friable soil that will hopefully give you healthy orchards for a long period of time,” he said.

To describe water-stable aggregates, he used the example of a little clod of soil added to a glass of water. If it falls to the bottom of the glass very quickly and is dissolved into all of its mineral matter, “I can guarantee you have soil that will be like concrete,” he said. This is characteristic of soil with a low percentage of water-soluble aggregates.

In comparison, a clod of soil with the desirable high percentage of water-soluble aggregates will rumble down to the bottom of the glass, but it will remain in little clumps rather than dissolving.

“In fact, I have some clumps — some water-stable aggregates — from Michigan soil that have been sitting in water for 10 years and still haven’t dissolved,” he said.

The future

Other parameters are coming to soil tests, he noted. Cornell has just added a soil-protein analysis. Two others that are being added are nitrification and carbon mineralization.

Soil-protein analysis and nitrification are both indicators of nitrogen utilization, and carbon mineralization measures the amount of carbon dioxide that soil microbes give off, thereby estimating how many bacteria are present in the soil and how active they are.

“There are other indicators that are being constantly evaluated, too,” he said, noting that scientists are currently working on microbe indices for beneficial microbes and for problem organisms, such as root-lesion nematodes, that can be added to soil test results and will have practical applications for orchardists.

Growers will be hearing about new soil-test parameters more and more frequently as the nation’s emphasis on soil-health research expands, Bird said.

As an example, he pointed to the USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service, which created a Division of Soil Health and added soil staff last year.

Several universities are also either starting or expanding their soil-health programs.

“It’s becoming a high research priority, and hopefully we can get it to snowball,” he said. “The soil is an interactive, biological, living system that participates in the food web and provides the nutrients for the plants, and the more we know about how this system works, the better we’re going to be able to utilize that knowledge on the farm.” •

– by Leslie Mertz, Ph.D., a freelance writer based in Gaylord, Michigan.

Leave A Comment