—story and photos by Ross Courtney

Once again, dogs are sniffing Washington orchards for little cherry disease.

This time, however, the fruit industry has tapped a handler with experience detecting agricultural pathogens.

“I know how to do this,” said Jessica Kohntopp, owner of Ruff Country K9 near Twin Falls, Idaho. “Give me a shot, give me a chance.”

She is getting that chance.

Kohntopp, who has led canine pathogen detection in Florida and California, is running her dogs through trials with Washington State University researchers to determine whether they can detect when a cherry tree is infected with X disease or little cherry virus more quickly than any other tool.

Industry experts required convincing. The previous two efforts — in partnership with an environmental group and kennel club volunteers — fell short, partially because neither group had a background or interest in production agriculture, said Ines Hanrahan, executive director of the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission.

WSU pathologist Scott Harper, director of the Clean Plant Center Northwest, was among the skeptics, but Kohntopp’s dogs are winning him over.

In an early blind trial, the dogs successfully sniffed out all seven pathogen-inoculated potted cherry trees — from a total of 187. They also both alerted on an eighth plant that researchers had thought was negative. When Harper later retested it with a PCR screen, it was infected, too.

“It really just shows that the dogs pick up things earlier,” Harper said.

And that’s the point.

Little cherry disease, a broad term for several pathogens that cause trees to produce small and pale fruit, is a big problem. There is no cure. Infected trees must be ripped out before they spread the disease to their neighbors, either through roots or insect vectors.

The trick is knowing which trees to remove. By the time symptoms appear, the disease likely has been around for years. Detection of little cherry disease is one of the top priorities of the research commission, which is funding Kohntopp along with money from the Northwest Nursery Improvement Institute. (See “Detection difficulties” at the end of this story.)

In the early stages of infection, pathogen levels tend to be low and may be isolated in only one branch. Because genetic screens are only as accurate as their samples, sometimes you get “lucky” with detectable pathogen levels in the sample, Harper said, but other samples test negative, even though the pathogen is lurking elsewhere in the tree.

“The dog is not stuck with that sampling limitation,” Harper said.

Dogs sniff the pathogen volatiles whether they are coming from a high branch or the roots.

Stacey Cooper, an Oregon cherry grower near The Dalles, also has been pleasantly surprised. She was frustrated with previous dog detection attempts but believes Kohntopp is on the right track, she said.

Cooper envisions dogs providing preventative screening, either detecting infected plants in nurseries or at an orchard before they go in the ground.

“I see it as a planting strategy,” she said.

Commercial-scale challenges

Kohntopp grew up visiting her grandparents’ farm in Twin Falls. She holds a bachelor’s degree in crop science from the University of Idaho, with minors in plant pathology and entomology. She also spent four years working as a handler for canine teams detecting citrus greening disease, which has devastated millions of acres of citrus crops in the United States and caused a 75 percent drop in production in Florida.

For more than 20 years, the U.S. Department of Agriculture studied the use of canines for early detection of citrus greening. In 2020, a research paper reported the dogs were sniffing out the disease with near-perfect scores. That caught the attention of The New York Times and Smithsonian Magazine, along with agricultural trade publications across the country.

Human handlers expect success from their dogs in this business. Goals typically involve accuracy of 90 percent or higher.

Few commercial efforts have followed the research, however. In Florida, citrus greening was already too widespread, said a spokeswoman for the state’s citrus department. Also, one of the dog-handling companies that was involved went through mergers that left it in the hands of an owner accused in a lawsuit of mismanaging $1 million of company money.

There are more examples of commercial detection dogs for insects. The Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture sends canines to look for pests, including spotted lanternfly, in nurseries during normal inspections.

In California and Arizona, Canine Detection Services of Fresno, California, is using six dogs to detect the Asian citrus psyllid, which transmits citrus greening disease, with funding from a federal grant and local pest control assessments. The company also recently finished a trial for detecting grapevine leafroll virus and its vector, vine mealybug, in Lodi, California. The Lodi Winegrape Commission is putting the final touches on an economic feasibility and scalability report.

“The jump from research to operations is a very tricky one,” Canine Detection Services owner Lisa Finke said.

Cherry results so far

Results of the two-year, $190,000 project in cherry show promise.

Kohntopp purchased her two detection dogs in June 2023 and trained them with potted plants that included samples inoculated with either the X phytoplasma or little cherry virus 2, then with “distractor” plants — potted cherry trees with other ailments.

The first trial was in March 2024, when the dogs surprisingly found the eighth positive plant from among healthy samples and distractors. The dogs had never seen the pots before, and Kohntopp did not know which were positive.

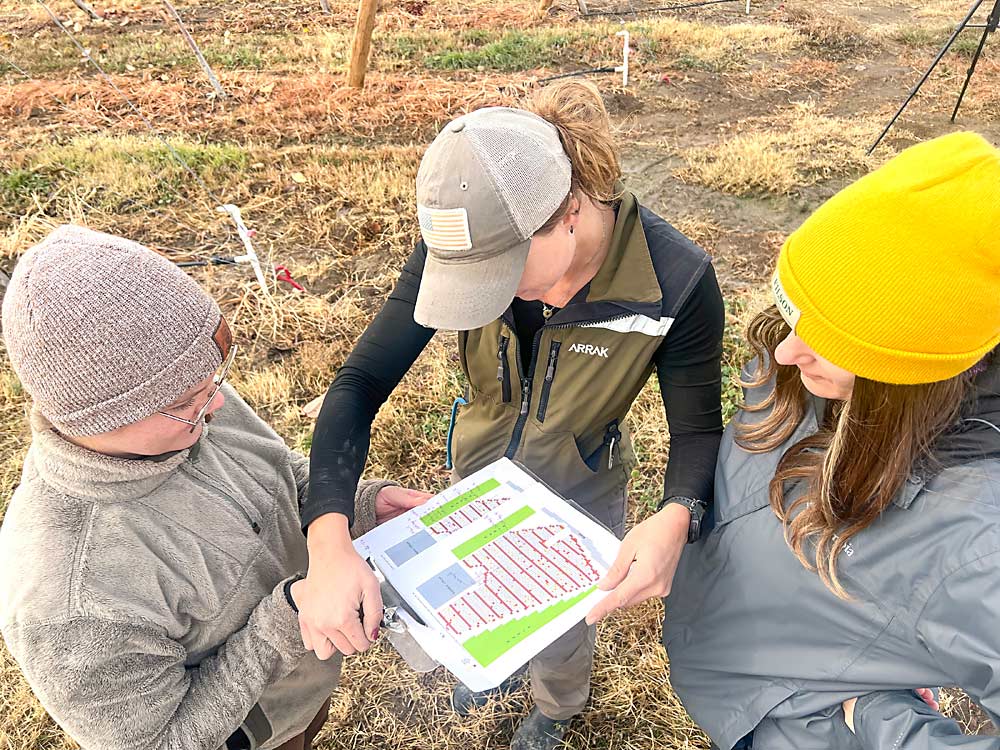

In April, Kohntopp ran her dogs at the USDA research orchard in Moxee, Washington, to train them to detect trees in the ground for the first time. Researchers had a map of which trees were infected.

The first large, blind trial was in July at WSU Prosser with 101 positive plants among a total of 1,380 — 60 plants at a time. Even though one of the dogs was ill, they combined for a 99.39 percent accuracy score, which accounts for finding positives and not falsely alerting negatives. In August, researchers organized another trial, about half the size, and the dogs combined for 99.72 percent accuracy.

During the fall months, the team ran trials in three blocks for a total of eight acres at the Zillah orchard owned by the research commission’s Hanrahan and her husband, Mark. Results were encouraging but inconclusive at the same time.

Two blocks had young trees with low infection rates, planted in spring 2023, an ideal situation for canine detection. The dogs alerted on a total of 31 trees. In five of those trees, PCR tests showed low levels of infection for either X disease or little cherry virus 2. PCR tests came back “non-detect” on the rest, said Corina Serban, the WSU extension educator for little cherry disease and Harper’s research partner on the project.

That doesn’t mean the dogs were wrong, though. The researchers could have sampled a noninfected portion of the tree, as early-stage infections are rarely systemic.

The older block, with trees 20 years or older, had many symptomatic and positive trees, many of them adjacent to each other. The dogs again found some of those positive trees and alerted on a few non-detects. However, those aren’t good conditions for canine detection, Kohntopp said. Dogs have such a keen sense of smell, they catch pathogen volatiles before they’ve even reached the correct tree; they can disregard weak infections as residual odors from another heavily infected tree nearby.

To wrap up the project by its May deadline, Serban and Harper will dig up and dissect five of the non-detect young trees the dogs marked as positive during the Zillah trials, to see if more thorough sampling can prove the dogs right.

Next steps

In the Northwest, growers are already lining up, said Mark Hanrahan.

“I think this is something the industry could really use at this point, because we have nothing else,” he said.

The fact that dogs are seemingly so much better than any other tool poses part of the commercialization challenge, though. The only way to validate the dogs’ work is to wait for symptoms to appear. That’s how researchers proved out the dogs in citrus greening, which progresses faster than little cherry disease.

“Of course, the industry wants the dogs tomorrow,” Serban said. “We have to have a compromise here.”

Kohntopp also would like more science backing up her work before she makes any sales pitches. She is seeking funding to follow her current project with nursery trials and is writing a business plan with the help of a Yakima-based economic nonprofit.

“I believe my dogs,” she said. “I believe up and down they are sitting on what they are supposed to be sitting on. But I don’t want to be selling snake oil either.” •

Editor’s note: The original version of this story included an error regarding the number of dogs now detecting Asian citrus psyllid for Canine Detection Services of Fresno, California. This story has been updated.

Detection difficulties

In recent years, the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission has funded a wide variety of research projects aimed to improve early detection of little cherry disease. Detection poses a particular challenge for young trees, which don’t bear fruit to show the namesake symptoms.

“The problem is that it requires you to have fruit on the trees, or you have to use a DNA-based method,” said Scott Harper, a Washington State University pathologist. DNA-based methods can be expensive, time consuming and require technically skilled staff.

Harper spoke at the 2025 Cherry Research Review, where scientists share their project updates with the industry funding their work. In 2024, the commission put nearly $250,000 toward little cherry disease detection, including digital noses, starch tests and next-generation genetic markers.

One promising project, led by WSU pathologist Frank Zhao, uses a new method of genetic amplification so that if even a single copy of the X disease phytoplasma presents in a sample, a targeted marker will bind to it. The method, very sensitive and accurate, can be done with a bulk processing approach to make it more affordable than current testing processes, Zhao said.

Harper and Oregon State University researcher Kelsey Galimba also tried some alternative approaches inspired by similar diseases — looking at iodine and other stains to see if infected plants show different patterns of starch accumulation — without much success.

Meanwhile, WSU engineer Lav Khot is leading work looking at plant volatiles. Using technology to track scent signatures using laboratory tools instead of dogs’ noses, he has identified several chemical biomarkers, at key stages of cherry development, that differentiate infected and healthy samples. Those biomarkers could be used to develop a portable, in-field testing system or help train detection dogs.

At present, all the detection approaches — dogs aside — face the same sampling challenge. If the infection is not yet widespread, taking a sample for testing under any approach might miss the presence of the pathogen.

Harper’s recent research proves this out: When researchers inoculated young trees, through leafhopper feeding or graft transmissions, detection levels were low. “It’s very unlikely to detect the pathogen in the first season,” he said. “After a dormancy cycle, many more are positive.”

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment