Making itself at home in Eastern Pennsylvania, the invasive spotted lanternfly has proven itself to be an enormous nuisance and serious threat to vineyards and to the economy of the region — both thanks to the resulting damage and to quarantine restrictions.

The striking leafhopper — distinguished by bright red underwings that give the gray spotted wings a rosy tint when crawling up a tree — has a wide host preference, sucking sap from woody plants that include fruit trees and landscape trees, but grapevines appear to be a favorite, along with the invasive and pervasive tree-of-heaven. Native to Southeast Asia, the spotted lanternfly, SLF, was first found in Berks County, Pennsylvania, in 2014.

Like brown marmorated stink bug before it, SLF is a nuisance for residents and difficult to control because it is found throughout the landscape, but due to its penchant for feeding swarms, it can kill a vineyard in one season.

“It’s pretty shocking damage, actually,” said Heather Leach, extension entomologist for Penn State University.

“With high feedings, we end up with vines that aren’t producing flowers and fruit or are completely dead,” she said. “I know one vineyard had 2.5 acres of Pinot Noir that was attacked in the fall of 2017 and in the spring, everything was dead. So, the damage is scary and happens quickly.”

Between 30 and 40 wine grape growers in the quarantined zone of Eastern Pennsylvania had spotted lanternfly damage in their vineyards last year, Leach said. The state is the fifth-largest producer of wine grapes and the third-largest producer of juice grapes in the country, although SLF has not yet been found in the juice grape growing region along Lake Erie.

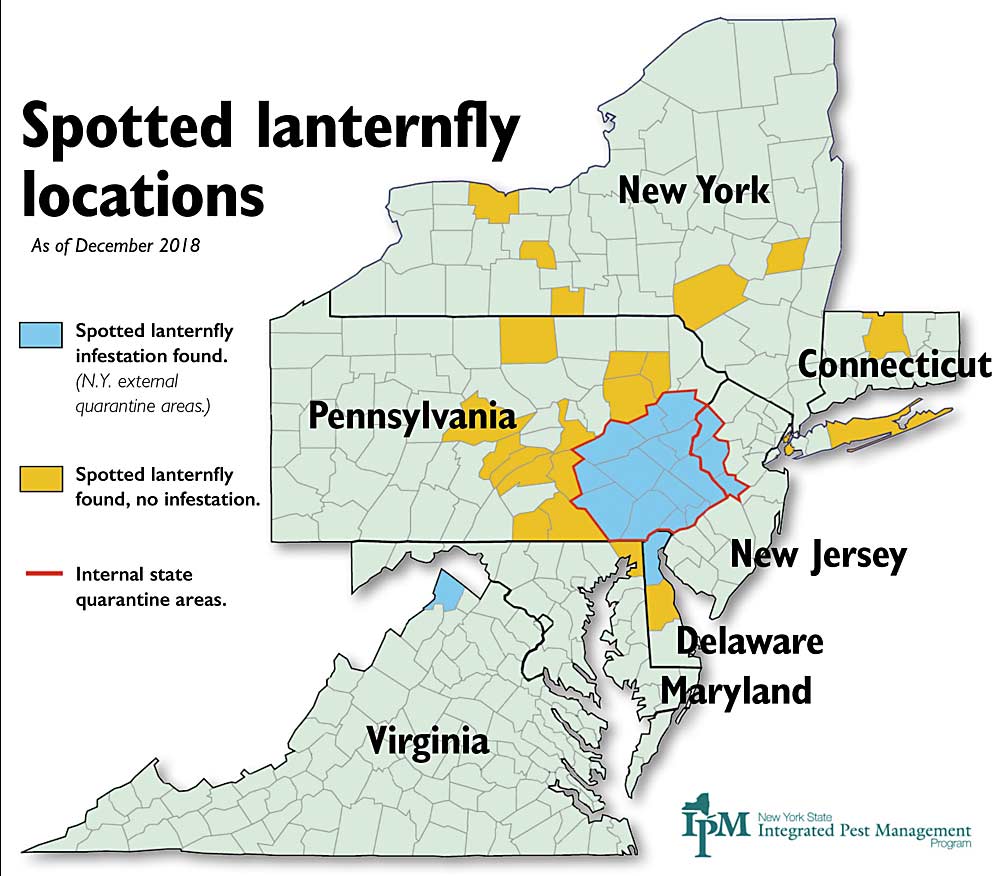

For now, the infestation remains largely restricted to 13 quarantined counties in Eastern Pennsylvania, along with three neighboring counties in New Jersey and one in Delaware. But there’s also a population growing around Winchester, Virginia, and SLF have been found in more than a dozen other counties in Pennsylvania, New York, Connecticut and Maryland.

Its ability to hitchhike with human movement poses the greatest concern.

SLF lays its gray, hard-to-spot egg masses indiscriminately, so moving trucks, Christmas trees, patio furniture or apple bins could all relocate the pest, said entomologist Sven-Erik Spichiger, who recently joined the Washington State Department of Agriculture from Pennsylvania. The Virginia population is believed to have been transported on landscaping material.

“Here’s the real issue: These things love to lay eggs on rusty metal, like a railcar, so it has high risk of transport,” Spichiger warned Washington grape growers at an industry meeting in November. “Make no mistake about it; it is coming here and probably quicker than you think.”

Management

The good news is that SLF is relatively easy to kill.

Familiar pyrethroid and neonicotinoid insecticides, such as Scorpion (dinotefuran), Actara (thiamethoxam), Brigade (bifenthrin) and Mustang Maxx (zeta-cypermethrin), along with Sevin (carbaryl), all work well, but since SLF have a wide host range across the landscape, new bugs can invade a recently treated area.

So, the challenge becomes balancing a long-lasting residual for the repeat invasion with the need for a low preharvest interval, as feeding swarms seem to peak in September, just as growers need to harvest, Leach said.

“I have heard growers using some of the longer residual products after harvest with good success,” she said. “It’s nice to spray some bifenthrin and have a break from worrying about it.”

Leach said she tells growers to spray when there are five to 10 SLF per vine, but that’s based more on anecdotal evidence, since they just don’t have enough data yet.

More research is underway at the university, state and federal level to learn how best to control SLF — including applied studies in vineyards to understand how much feeding vines can tolerate and to establish management thresholds, develop pheromone lures and traps, and hunt for effective biocontrols.

“Our top priority right now is making sure vineyards have better management options,” she said. “To be honest, there is just still a lot we don’t know.”

It is well-established that growers and homeowners alike should remove tree-of-heaven or treat the trees with a systemic insecticide. The state of Pennsylvania and U.S. Department of Agriculture are working together on a program to treat the trees to kill SLF as well.

Wrapping trunks of infested trees with sticky tape can also kill the flightless nymphs, which are black with white spots in the early stages of development and then turn red with black and white spots as they mature.

On the lookout

Swarms of SLF have been found feeding on peach and apple trees as well, but it’s much shorter-lived and growers haven’t yet seen economic damage to tree health, Leach said.

Harvesting clean fruit in the midst of a pest swarm poses a challenge for commercial operations that need to ensure bins are pest-free before shipping out of the quarantine region — and debilitating for pick-your-own and other agritourism businesses.

“It’s literally swarming orchards during picking and packing,” Spichiger said.

Ed Weaver, who owns a farm market and pick-your-own farm in Morgantown, Pennsylvania, said SLF prefers tree-of-heaven, maple and birch on his property more than apple trees, at least so far. He first spotted the bugs in 2017 and saw a significant population last year.

“The negative impact has just been more the customer experience,” he said. “For people who come from out west of our farm and had not experienced them yet, they were freaked out.”

Grape growers in adjacent regions are also a bit freaked out. In New York, the focus is on education and outreach, so that farmers and citizens are prepared to identify and report the pest before it has time to establish, said Tim Weigle, statewide grape IPM extension educator at Cornell University.

The IPM program has combined forces with state and federal regulators to establish a command center to respond to SLF sightings, he said — the first time such a coordinated response has been launched for an invasive insect.

“We’re hoping we can keep it to a dull roar,” Weigle said. “I don’t think we can completely prevent it, but hopefully we can keep it down until we have the biological controls.”

Leach said the controversial quarantine, which adds expenses to any business moving product out of the regulated region, appears to be working to slow the spread of the pest, but ultimately is unlikely to contain it completely.

“Because it hitchhikes so well, they can go cross-country very easily,” Weigle said. “If I was a grape grower anywhere in the U.S., I’d make sure I know what this pest looks like.” •

—by Kate Prengaman

I just planted a grapevine in the spring and just today 9 20 21 noticed a bunch of SLF. Should I cut it down since its young

Hi Dwight, I recommend contacting your local university extension office for advice on managing your grapevine and killing the spotted lantern fly you found. Especially if you are outside the known area for SLF sightings — they’ll want to know about it.