For a few years, spotted lanternfly appeared to be an existential threat to vineyards in Eastern Pennsylvania. First discovered in the region in 2014, the invasive planthopper was starting to do real damage by 2017, flooding vineyards in huge numbers and feeding on — and killing — grapevines.

Growers fought back valiantly, mostly with extra spray applications, but the spotted lanternflies kept coming. Many growers felt like they were fighting a losing battle and put their future vineyard plans on hold.

By 2021, however, the flood had dwindled to a trickle. No one is quite sure why — or how long the reprieve will last — but they hope the worst is over.

In Eastern Pennsylvania, at least. As that region’s grape growers catch their breath, the spotted lanternfly (Lycorma delicatula) continues to expand beyond its epicenter, and now with vineyards in surrounding states as the new battlegrounds, research continues into control techniques.

Dispersal or disappearance?

Native to Asia, adult spotted lanternflies are about an inch long and have gray upper wings with distinctive black spots and red and black hind wings, which give them a rosy tint at rest. Nymphs are black with white spots in earlier stages of development, and in their final instar they are black and red with white spots. Egg masses are gray. Its preferred host is tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima). The insect has many other hosts, including fruit trees and hop bines, but it feeds voraciously on grapevines — and because it’s so new to the United States, little is known about its biology and behavior.

No one is sure why spotted lanternfly, SLF, disappeared in Eastern Pennsylvania. It might mean the management recommendations developed by Penn State University are working. More likely, SLF’s massive numbers temporarily depleted local resources, and the insects moved to more promising feeding grounds. The pressure could very well return, said PSU associate research professor Julie Urban, who is coordinating a four-year, $7.3 million research project funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture to study spotted lanternfly.

“(Spotted lanternfly) is the biggest threat we’ve had to the vineyard since we’ve been growing grapes,” said Eastern Pennsylvania grower John Landis.

Landis first noticed a small number of spotted lanternflies in his vineyard in 2017, followed by a “heavy infestation” in 2018 and 2019 — over 300 flies per plant on some vines. Some of the vines were so weakened by feeding that they didn’t survive the following winter. Landis estimated that he lost about 8 percent of the vines in his 25-acre vineyard.

The infestation abated somewhat in 2020, and by 2021 Landis found only a handful of SLF.

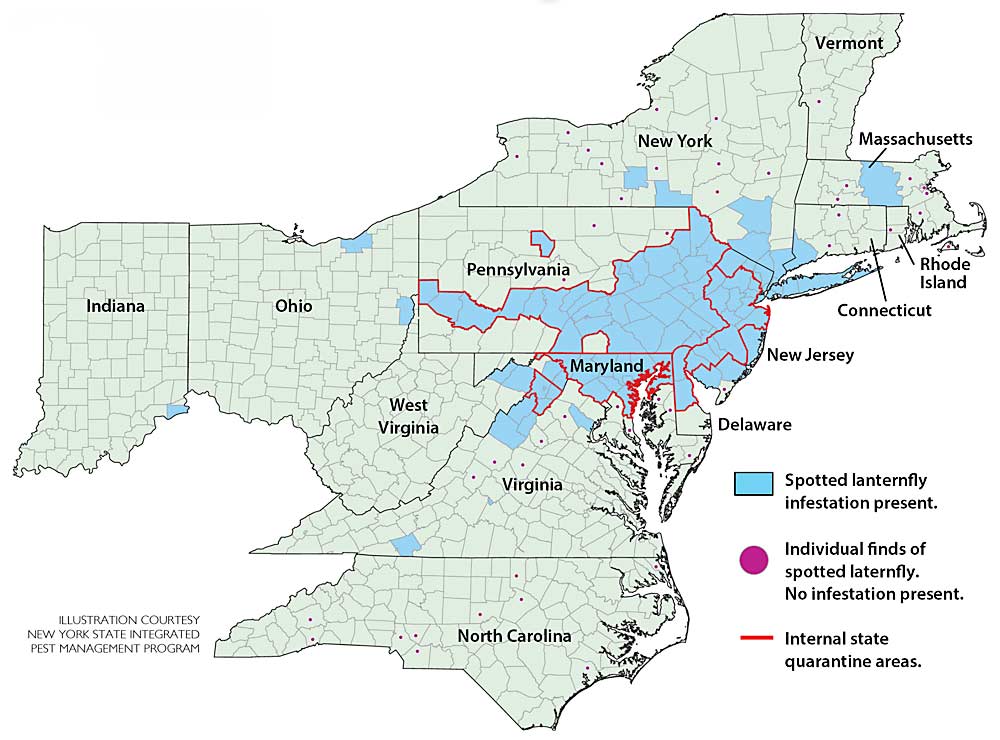

Even if spotted lanternfly never reinvades Eastern Pennsylvania, the pest is not going away. SLF infestations are now present in at least 11 states, with individual insects (often, but not always, dead) found as far away as the Pacific Northwest. And even though Pennsylvania and neighboring states have set up quarantine zones, the invader is creeping closer to other grape regions, including New York’s Finger Lakes and Erie, Pennsylvania.

Observers are starting to notice a pattern to SLF’s movements. The bug will stick to a “hot spot” for a couple of years, feeding from a broad range of host plants, before spreading into surrounding areas, which become the new hot spots, said Rutgers University entomologist Anne Nielsen.

That’s what seems to be happening in New Jersey. Spotted lanternfly was detected there in 2018, but in low numbers. The population exploded in 2020 and 2021, and New Jersey’s SLF quarantine has grown to 14 counties. As of last year, 80 percent of New Jersey vineyards had reported infestations, Nielsen said.

Maryland hasn’t been hit as hard as New Jersey, but it seems to be fitting the pattern. A few vineyards saw low numbers of SLF in 2020, and some had to spray last year to manage late-season feeding. But 2022 will be the third season, which seems to be when SLF pressure becomes very intense, said Joe Fiola, viticulture and small fruit specialist with University of Maryland Extension.

Urban said Pennsylvania’s experience with the pest, and the information that’s been shared among researchers the past few years, has helped growers in other states prepare for the spotted lanternfly invasion.

“Pennsylvania is now managing (spotted lanternfly) pretty successfully, to the point where it’s not necessarily a massive battle every year,” Fiola said. “We hope that will be the case in Maryland.”

Management

What makes spotted lanternfly so devastating to vineyards is its ability to damage, and possibly kill, grapevines. Penn State viticulture professor Michela Centinari studies the pest’s effects on long-term vine health. She said high numbers of SLF feeding on a single vine can remove a large amount of nutrients and sugars from its sap, which can compromise the ability of the vine to properly ripen fruit and stay healthy in the long run.

According to Penn State, insecticide applications remain the most reliable way to manage spotted lanternfly. The most effective insecticides include: dinotefuran (Scorpion, Venom), imidacloprid (Admire Pro), beta-cyfluthrin (Baythroid), bifenthrin (Brigade, Bifenture), fenpropathrin (Danitol), thiamethoxam (Actara), carbaryl (Carbaryl, Sevin) and zeta-cypermethrin (Mustang Maxx).

SLF pressure worsens from late August through November, when adults arrive in vineyards in large numbers to feed. Populations peak in September, during harvest, complicating the timing of spraying and picking decisions.

Penn State researchers are also studying alternatives to insecticides. Professor and extension entomologist Greg Krawczyk and graduate student Sarah Henderson are evaluating the feasibility of using netting walls to protect grapevines at Landis’ vineyard in Eastern Pennsylvania.

The researchers constructed an 8-foot-high wall of horticultural netting and stood it between the outermost row of grapes and the adjoining landscape, with the goal of blocking spotted lanternfly from the vineyard. After two years of trials, they’ve proven that such a wall can prevent many SLF adults from entering, but it can’t stop enough of the pests to make a netting wall an economically viable option, Krawczyk said.

For one thing, the wall needs to be taller than the surrounding vegetation. If the vineyard is surrounded by taller trees, the lanternfly adults in the trees will simply fly over the net, he said.

Draping bird netting over the vines isn’t effective, either. Draped netting leaves openings near the row bottoms, where an SLF adult will simply walk in and begin feeding, Krawczyk said.

—by Matt Milkovich

Leave A Comment