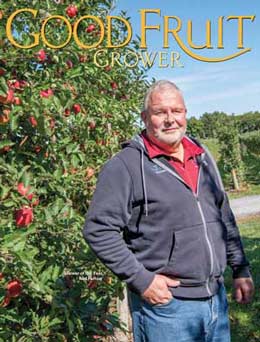

When Rod Farrow first saw super spindle orchards during an International Fruit Tree Association tour in British Columbia, it was love at first sight. But without extra trees in his farm’s own nursery, he might never have tried it.

“If we hadn’t been growing our own nursery, there’s no way (we) would have spent that much on trees,” Farrow said. “We haven’t bought a nursery tree since 1992.”

He credits the savings in tree costs as a significant part of his farm’s success. However, it’s the exact opposite of easy money.

“To me, in order to be a really good grower, you have to do everything on time, and you have to be able to do the nursery work first,” he said. “Nursery timing is even more critical.”

Deciding to scale up the nursery to produce enough trees to transition most of the orchard to super spindle systems actually made the nursery work easier, Farrow said, because the bigger nursery program justified dedicated machinery and staff.

The financial benefit goes beyond simply the tree prices, Farrow said, because it allowed him to use cash flow for the investment in new plantings. Rather than writing a big check before planting, he spread out the investment in tree production, with much of the cost coming through payroll.

“It’s helped enable us to plant trees every year,” he said.

Over the years, Farrow and his partners, Jose Iniguez and Jason Woodworth, refined their nursery approach.

“At first, we were just trying to grow trees as cheaply as possible, using one-year bench grafts” to fill out the super spindle plantings, Woodworth said. But as they saw how long it took to grow those trees into production, they began to explore how to produce better trees.

Now, they leave the trees a year longer in the nursery — an approach commonly known as letting the trees grow through — and encourage dozens of small branches to produce trees designed specifically for their super spindle system. At transplant, the “designer trees” are usually 8 or 9 feet tall in a system that tops out at 11.

“It’s trying to find the tree that fits into the orchard basically ready to go, and leave all the juvenility in the nursery,” Farrow said.

If they discover a newly selected variety is not going to be successful, Farrow has no qualms about grafting over a young block to swap out the scion.

“The fact that we have a system and it’s cheap to flip it, I wouldn’t mind risking any good variety because I know our cost to change is very small,” Farrow said.

Farrow credits Mike Argo, owner of Argo’s Grafting Co. in Yakima, Washington, with teaching him a side grafting technique that works wonderfully in his super spindle system. “It was fantastic he was willing to share it,” Farrow said, adding that Argo agreed to teach him because he was too busy in Washington to come to New York regularly.

For years, Farrow’s team would cut off the trees to graft, leaving only a nurse limb. Then, he began borrowing an idea he learned on a tour of Trever Meachum’s orchard in Michigan. Meachum cleared the lower trunk of branches, to give the graft a sunny spot, but otherwise left the top of the tree for one last crop, Farrow said.

With this approach, he only sacrifices one year of production. In the grafting year, the new wood usually gets 2 to 3 feet of growth, but the old scion still picks 50 bins an acre instead of the usual 70, Farrow said. Then they whack off the top, lose a crop year training a new tree, and crop 30 to 40 bins an acre the following year.

“He just took (the grafting technique) and ran with it and did great,” Argo said. A nurseryman himself, he complimented Farrow’s work there as well.

“When you work with a tree from a bench graft state, like Rod does, he can grow the whole tree perfectly — the limbs, the leaders, it’s all dialed in,” he said. “Not a lot of people can do that. It’s becoming a gardener instead of an orchardist, and you really have to change your mindset to where you can be a gardener to give them what they need.”

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment