Tree fruit shippers face seemingly opposite marketplace demands of sustainability and convenience and are trying to move in both directions at once, rolling out paper-based containers, shipping cherries in recyclable trays and working with manufacturers to develop compostable plastics.

And if they want people to eat more apples, they had better embrace that incongruity, said several speakers at the Washington State Tree Fruit Association Annual Meeting in December in Kennewick.

“You can say, ‘Those whippersnappers, aren’t they all about saving the planet and they want to buy bags instead of bulk?’ Bulk is the most sustainable package we pack, but they want bags,” said Steve Clement, CEO of Sage Fruit Co. in Washington’s Yakima Valley, during his consumer trends presentation.

“The more correct way to probably look at it is to say they want bags, and they also care about the environment,” he said.

A few vendors displayed alternative packaging and labeling equipment at the adjacent trade show.

Canada complications

Canada might become the next tightrope. The Canadian government has proposed banning the use of noncompostable plastic PLU stickers and mandating 75 percent of produce be distributed plastic-free by 2026. That would jump to 95 percent by 2028.

“That’s an audacious goal,” said Brianna Shales, marketing director for Stemilt Growers of Wenatchee, Washington.

The tree fruit industry has joined other groups in pushing back, arguing the regulations would drive grocery prices even higher, cause more waste and make it nearly impossible to ship cut lettuce, raspberries and cherries.

“You’re literally going to eliminate products from the grocery store,” said Dennis Nuxoll, vice president of federal government affairs for Western Growers, which represents specialty crop producers in five Western states.

Canadians import most of their fresh produce — due to the country’s limited growing seasons. The U.S. is far and away their biggest supplier. In 2023, Northwest producers shipped $77 million worth of sweet cherries to Canada. China was a distant second at $38 million.

The Canadian Produce Marketing Association sent a letter to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau expressing similar “very significant concerns.” The additional food waste alone would cost an extra $160 per year for every Canadian, the group estimated.

The Northwest Horticultural Council, which represents Oregon and Washington tree fruit in federal and international matters, supports the objections of the CPMA and Western Growers, said Dan Langager, technical communications manager.

Efforts so far

Sustainable packaging challenges started well before Canada’s proposal, and the fruit industry responded by exploring both packaging and political options.

For one, Washington’s tree fruit industry is lobbying its state government for a sales and use tax break on reusable packaging. Citing consumer demand, Costco began replacing plastic apple clamshells with cardboard in 2021. France already forbids noncompostable PLU stickers and restricts plastic produce packaging — with certain exceptions. Displays of fiber-based boxes are common at international tree fruit trade shows and have started showing up at U.S. events.

“It’s a really tough spot for the produce industry, and I feel for them,” said Brant Carman, West Coast sales manager for 4HM Solutions, a Florida-based packing material and equipment company serving many produce segments, including tree fruit.

However, automated packaging with paper or other fibers is possible, he said. 4HM has partnered with Italian company Frutmac to distribute tools that automatically fill and close carboard tray packages. The company has a demonstration machine ready to install and is looking to market fiber-based clamshell packages and cardboard-like trays made from grass fiber.

About those PLU labels?

Private and government researchers are working on compostable versions, but developing a product that can withstand the rigors of shipping is tricky, said Dwayne Brandon, CEO and founder of PrinTrayce Systems in Gresham, Oregon, which manufactures and sells labels and labeling equipment.

“Compostable labels and adhesive can potentially turn into a gooey mess before you want them to,” he said.

Lasers that burn images onto fruit have been around for years, but the little foothold they have gained has been with skins you don’t usually eat, like oranges or watermelons, he said.

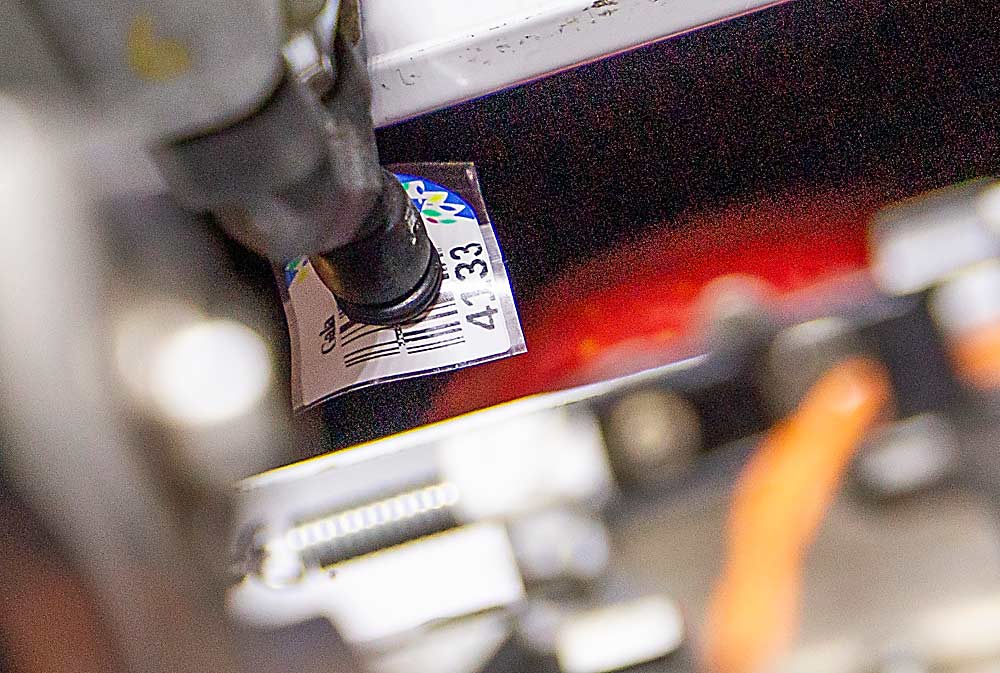

For now, PrinTrayce offers equipment that applies liner-free labels, cutting plastic use by half. The machines do their work at the end of the packing line, right before the trays are packed into the box. That helps keep the grading equipment clean on commit-to-pack lines.

Still, the Canadian proposal has PrinTrayce Systems and its suppliers developing a wood fiber film and adhesive that will allegedly compost better than paper labels.

“None of our customers have demanded it, but we hope to have a label product ready should the request arise,” Brandon said.

Some Northwest tree fruit companies have their own products.

Stemilt, one of the early adopters of the Costco box, has just begun using the EZ Band, a paperboard four-pack with a band across the top to hold fruit securely. The new box was inspired by packaging common in European stores.

But it’s not automated yet, Shales said. They let a few customers try the packaging in 2023 and will expand to more this year as retailers use it for organic marketing, but it won’t reach the thresholds Canada proposes, she said.

Paper packaging usually requires hand labor, said Tyler Weinbender, director of sustainability and packaging for Domex Superfresh Growers, a vertically integrated producer in Yakima. Automated solutions exist, but the high capital layout is hard to justify for only one or two customers, he said.

His company is instead doubling down on recycling.

Domex now fills film bags made with at least 20 percent postconsumer recycled plastic, or PCR. Industrywide, clamshells have had some PCR for years, he said, but Domex has set a minimum of 70 percent.

However, with too much PCR resin the container ends up cloudy, he said. Retailers like bags people can see through. Also, the supply chain only has so much PCR resin available because consumers don’t recycle as much as they could. Domex’s bag would qualify for in-store recyclable plastic collection drop-off bins, he said.

“We can spend all this time developing the right bag. The consumer still has to recycle,” he said.

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment