Under the canopy, a mechanical claw reaches out to grasp the trunk, clamps and shakes violently, sending a cascade of bright red cherries onto a conveyor belt.

The scene, so common in Michigan, plays out in Eastern Washington, in the heart of a fruit region used to seeing cherries picked by hand.

Dorsing Farms of Royal City is one of just three Washington orchards commercially producing tart cherries, harvested mechanically and used in everything from pies to juice to trail mix.

The family has grown tart cherries for 25 years or so, said Patrick Dorsing, general manager.

The Dorsings’ tart cherry harvesters are actually two independent machines operating as a team on opposite sides of the row. The side shown here includes the clamp and arm to violently shake the tree while the other component collects the fruit on a conveyor belt. (Ross Courtney/Good Fruit Grower)

Dorsing’s late grandfather Karl Dorsing, known for experimenting, first led the farm into the tart cherry business. “He was someone who was just growing things that were just different around here,” Patrick Dorsing said.

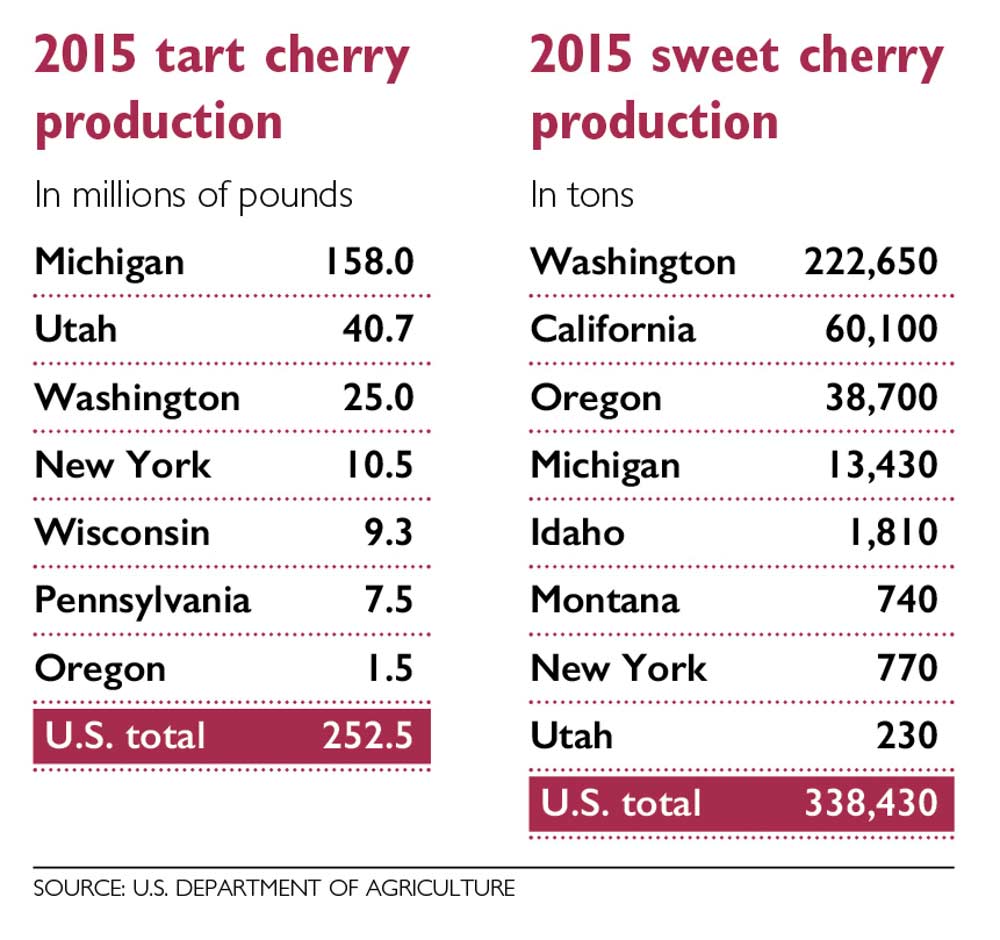

The three farms, all located in the Columbia Basin, together make Washington the nation’s third-largest tart cherry producer behind Michigan and Utah. New York, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania and Oregon round out the Top 7.

Those same seven states are members of a federal marketing order, created in 1997 to stabilize supply and demand.

Regardless of rank, when it comes to scale, nobody compares to Michigan, home to 63 percent of the nation’s crop.

Washington, on the other hand, is the land of sweet cherries, packed for the fresh market. The state produces two-thirds or more of the nation’s sweet cherries, depending on the year.

Tart cherries, though they’ve been around for more than 30 years in Washington, still catch people by surprise. “It’s been an educational process for 30 years,” said Mike Rowley, a partner in Rowley and Hawkins Fruit Farm in Mesa, Washington, and fifth-generation tart cherry grower.

Three farms

The three businesses all produce primarily Montmorency cherries, by far the most common variety in America.

They all are vertically integrated with their own processing facilities, after operating for many years within a cooperative named Washington Tart Cherries.

And they all have followed the industry trend away from dessert ingredients toward concentrate and dried cherries for snack food, such as yogurt dipped cherries and trail mix, fueled by media reports of the health benefits of tart cherries.

When Rowley’s father moved his family’s business from Utah to Washington in 1981, about 95 percent of the nation’s Montmorency cherries went to desserts, such as pie fillings. “Today, that number is more like 40 percent,” he said.

“We are always looking for new avenues to sell our cherries,” Rowley said.

Tart cherries grow well in Central Washington, just like their sweet cousins, Rowley said. Washington growers claim they get higher yield because of the prevalence of irrigation. The family has about 600 acres. The packing and retail side of the business is called Northwest Tart Cherry.

The family also grows other fruits, berries and asparagus, but 80 percent of its overall production is tart cherries.

The conveyor belt half of the cherry harvester collects shaken cherries. (Ross Courtney/Good Fruit Grower)

The biggest difference between growing sweet and tart cherries is the harvest. Sweet cherries are picked for the fresh market by hand.

Tart cherries are almost all processed and harvested by shaking machines, which are still evolving.

Michigan State University and private vendors have been experimenting with over-the-row harvesters to pick tart cherries like berries or grapes.

Also, tart cherries fetch lower prices and deliver smaller profit margins.

Ivan Taylor, owner of TICO Farms in Basin City, Washington, stumbled into the tart cherry business accidentally in the early 1990s, when he bought a nearby farm that had some tart cherry trees.

Today, he has 400 acres of Montmorency cherries, producing the bulk of his family’s business, which also grows some plums and leases out some row crop land. “It turned out to be a pretty good deal,” he said.

Taylor built his processing facility in 1997 in nearby Othello. The processing arm of the business is named TPG Enterprises, which relies heavily on the juice market.

“Most of our cherries have gone into concentrate over the past 10 years,” he said.

Taylor called the industry relatively stable due to the marketing order.

“It’s taken some of the highs and lows out, especially the lows,” he said. •

-by Ross Courtney

I just can’t help myself, gotta leave a comment: …. why. why. why would anyone create the table in this article with vastly different scales????

Millions of pounds vs. tons???? Whaaat?

Such an easy conversion, but as presented makes the graphic worthless.

Good Catch Floyd!

Floyd and Joe, thanks for the comments on this. I’ve quickly ran the numbers to convert to tons (tart cherry production only) so you can better compare tart and sweet a bit easier. Hope this helps!

2015 tart cherry production: in tons

Michigan: 79,000

Utah: 20,000

Washington: 12,500

New York: 5,250

Wisconsin: 4,650

Pennsylvania: 3,750

Oregon: 750

U.S. total:126,250