Door County, Wisconsin, once grew so many tart cherries it was known as “Cherryland.”

The surrounding waters of Green Bay and Lake Michigan temper the climate of the Door Peninsula, which juts into the lake as Wisconsin’s “thumb,” making the region as hospitable to cherries as it’s always been. Yet, the Cherryland era didn’t last, for a whole host of reasons, including rising land prices and competition.

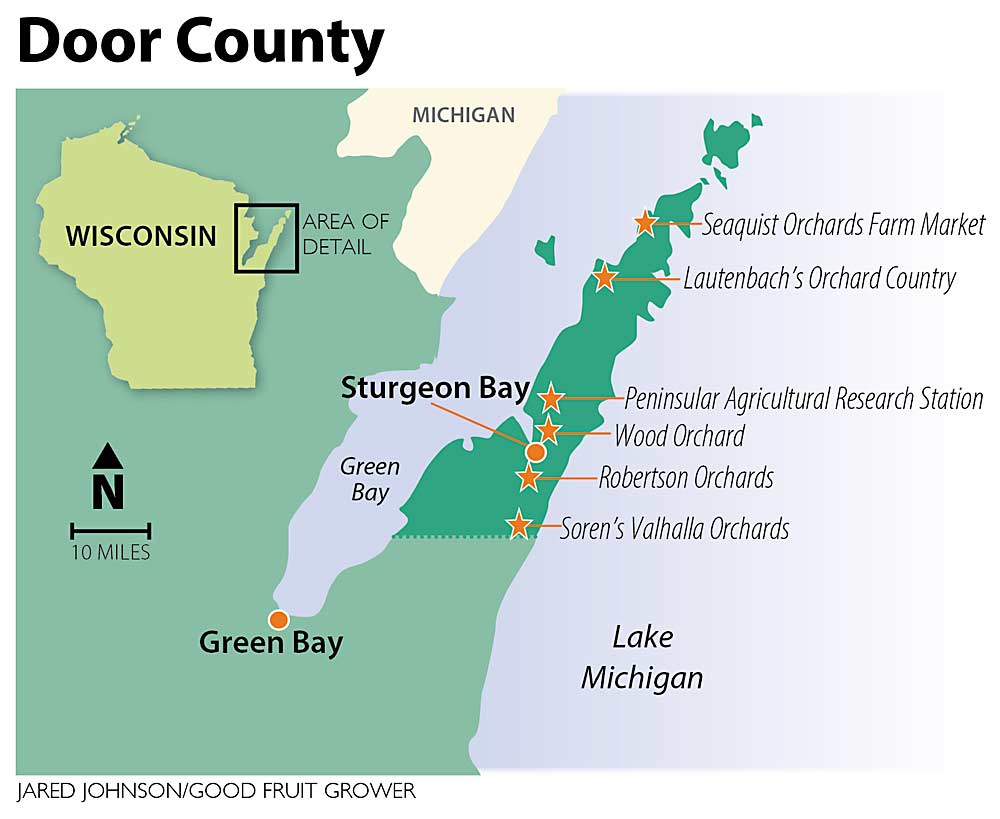

Today, Door County, which encompasses most of the Door Peninsula, remains a diverse fruit region, and its orchards — most of which have been managed by the same families for generations — continue to be a draw for millions of tourists. So much so that direct sales have kept many plantings of cherries, apples, grapes and other fruit in the ground.

Good Fruit Grower visited the region to learn more about the growers and crops that sustain its fruit industry.

Cherry history

Door County once produced the vast majority of the nation’s tart cherry crop, said Carrie Lautenbach-Viste, a third-generation cherry grower. However, a lack of distribution and marketing resources, volatile crop sizes, the expansion of other growing regions, and a tourism influx that inflated the price of land all contributed to an industry decline over the years.

Grower Jim Seaquist said Door County’s tart cherry production peaked in 1949, when 400 growers produced 50 million pounds on 10,000 acres. Today, those numbers are down to 10 commercial growers producing about 10 million pounds on 2,000 acres, along with a half-dozen orchards that grow tart cherries strictly for U-pick customers.

Seaquist said many of the county’s small family farms didn’t survive the transition to mechanical harvest — and the consolidation that accompanied it.

“The mid- to late ’60s was a rough time in the cherry industry,” he said. “It really trimmed the acreage down.”

Few fruit growers have deeper roots in the region than Seaquist. His family first moved to Door County in 1862, and his great-grandfather started raising Montmorency cherries in the early 1900s. His father, Dale, ran the family orchard’s first mechanical trunk shaker in 1972, the year Seaquist joined the harvest crew at 10 years old.

Seaquist, now 59, partnered with his father in the early 1980s. They were harvesting about 200 acres of cherries at the time. Four decades later, the family has 1,200 acres, making them the largest cherry grower on the peninsula. They also grow 50 acres of apples, mostly Honeycrisp, he said.

The Seaquist family currently operates four business entities: a farm, processing facility, retail market and canning company. Their processing facility handles most of the tart cherries grown on the peninsula. The commercial kitchen and cannery, their most recent endeavor, has been a good source of new sales. It also runs nearly year-round, which helps keep workers employed, he said.

Like employers everywhere, the Seaquists are struggling to find and keep workers. They’re raising wages and improving housing — anything to keep people returning. They hired H-2A workers from Mexico for the first time in 2021, he said.

Tart cherry profits have been dismal for the last few years, but Seaquist remains committed to the industry. For him, the volatility is part of the fun.

“There’s always been electricity around tart cherries,” he said. “That’s what’s interesting about them.”

Terry and Toni Sorenson are a rarity for Door County: first-generation cherry growers. They grow about 85 acres of tart cherries and 10 acres of sweet cherries. Most of their tarts are processed at the Seaquist facility, though some are sold U-pick.

The Sorensons knew tart cherries wouldn’t be easy. A winter freeze killed their first crop in 2008, and both have off-farm jobs to help pay the bills. But they saw a future in tart cherries, based on the fruit’s long tradition in the region.

“I tell my dairy farmer friends it’s like buying a heifer calf and taking care of it for six years before you actually return any revenue,” Terry said.

Cherry leaf spot and American brown rot are frequent challenges, but the onset of spotted wing drosophila several years ago added new complications.

“That beast has really changed the way we manage our trees,” he said. “We used to do an alternate-row spray, but we’re doing full cover now, both sides.”

The Door Peninsula is notorious for its rocky ground — a thin layer of topsoil covering a hard bed of dolomitic limestone. Fruit trees are fiendishly difficult to plant and remove. Growers used dynamite in the old days. They use less destructive tools — such as augers — now, but getting trees and posts to the proper depth can still be a struggle, said Rebecca Wiepz, superintendent of the University of Wisconsin’s Peninsular Agricultural Research Station, which has been conducting fruit research on the peninsula for nearly a century.

“You’re guaranteed to find a rock everywhere you dig,” said apple and cherry grower Skipp Robertson. “When it comes time to dig trees out, if a stump is intertwined with a big rock, you may not be able to get it out.”

The rocky ground poses challenges, but it has certain advantages, Seaquist said. The thin soils control vigor, and the highly fractured bedrock underneath provides good drainage. This keeps his Montmorency trees a little smaller, which leads to better light interception and sweeter, firmer cherries.

Apples

Steve Wood and his son, Jeff, are the only large-scale commercial apple growers in Door County, with about 130 acres.

Steve, now 75, moved to Door County from St. Louis in 1955, when his parents bought 40 acres.

“They wanted to make a living here, so they chose growing apples — for better or worse,” he said with a laugh.

Steve’s dad focused on wholesaling apples to regional grocery stores. That’s still the Woods’ main sales avenue, but in the 1990s, they discovered the potential of Honeycrisp and decided to build a farm market to boost sales of that variety. Direct sales have been an important part of their program ever since.

“We were the first to plant Honeycrisp commercially in Door County,” Steve said.

The Woods practice modern orcharding, using trellises, posts, tight plantings and fabric for coloring high-value varieties like Honeycrisp, SweeTango and Rave. They’re always on the lookout for new varieties to fit into their marketing plan, but the peninsula’s cold and short growing season won’t allow them to plant later varieties such as Fuji or EverCrisp.

They pack most of their apples in their on-farm packing shed and send the excess to sheds in Michigan and Minnesota.

“We have 60,000 bushels or so of CA storage,” Jeff said. “That’s a good-size packing line for Wisconsin, but small in the grand scheme of things.”

Labor for harvest and packing is scarce, at least until tourism season slows in late October. They hire local people for the packing line, and most of their pickers come from Florida. They’re considering buying mechanical platforms to assist with hand labor tasks, Jeff said.

The rocky ground is tough on apples, too. They have to irrigate most of their acres because their soil can’t hold much water.

“In a normal year, we’ll get timely rains,” Jeff said. “But never is there a normal year.”

—by Matt Milkovich

Leave A Comment