It takes years for X phytoplasma to make its presence apparent to the human eye — the small, poorly colored, off-tasting and unmarketable cherries that gave rise to the common name little cherry disease. That’s a real problem for growers trying to get ahead of the pathogen’s spread in their orchards.

“We don’t have rapid, non-contact sensing for symptoms. We have visual scouting that is laborious,” said Lav Khot, associate professor of biological systems engineering at Washington State University. Meanwhile, sending samples to labs for PCR testing is expensive because of the skilled expertise required.

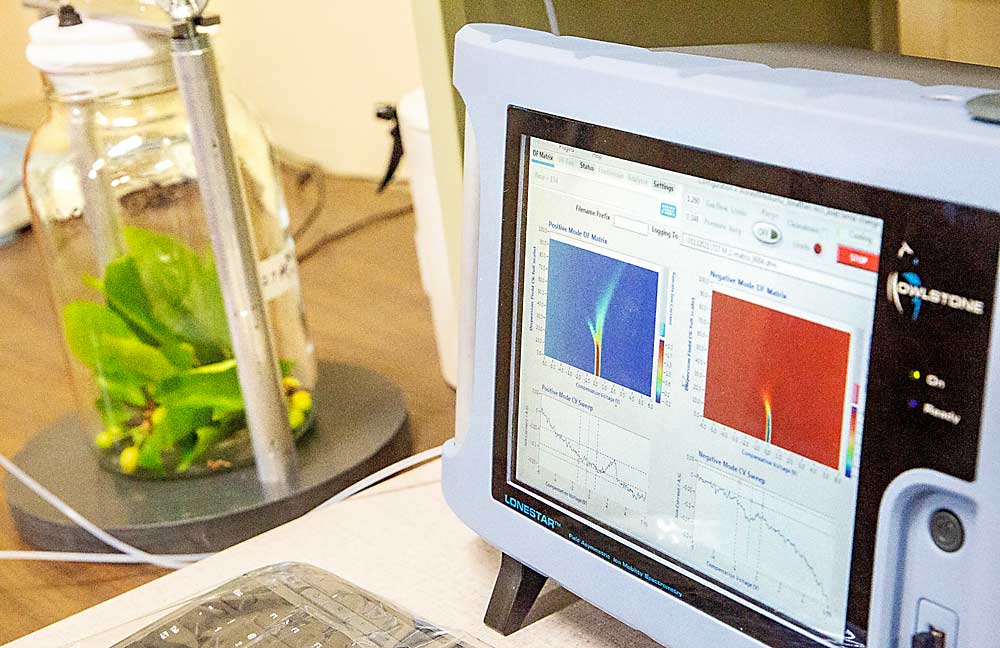

That’s why Khot and his colleagues at WSU’s Irrigated Agriculture Research and Extension Center in Prosser have developed a new approach to detection using a “digital nose” to track changes in the volatile compounds that cherry trees produce when infected with the X phytoplasma. Field samples are placed in a glass jar connected to a portable type of mass spectrometry machine to characterize the aromas they release. Researchers have found distinct differences between infected and healthy cherry samples, Khot told the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission, which is funding the work, but more research is needed to refine the approach.

Development of better tools for early detection of little cherry disease remains a top priority for the Northwest cherry industry, as does more research into how to control the leafhoppers that transmit X disease. The research commission and the Oregon Sweet Cherry Commission recently allocated $386,837 to new projects related to little cherry disease, along with $358,000 to support continued research into the sources of X disease in orchards, replant strategies for infected orchards (see “Removing the root risk”) and fundamental research into the pathogens that cause little cherry disease (LCD).

Here’s an overview of the new projects:

Toward identification of LCD-linked volatile biomarkers: Khot’s electronic nose project will move forward from a pilot project, with two years of research planned to study how the volatile detection approach can be applied for two cultivars, Bing and Skeena, and throughout the season — with the hope that the distinctive volatile patterns can be detected earlier in the season. Also, the researchers plan to work with the detection dog team and share samples to help the dogs learn to detect the key indicator volatiles as well.

Canine LCD detection skills applied to nursery and orchard settings: This collaboration between the Wenatchee Kennel Club, WSU, Texas Tech University and several growers aims to build on previous work showing that dogs can be trained to detect the infected cherry samples by training dog/handler teams to work in orchard settings. Long-term goals include training dog teams to map LCD presence in orchards and workshops to teach orchardists, fieldmen and others how to train their dogs to do this work.

Physiology-based identification of X disease-infected cherry trees: Another rapid-detection approach, this project aims to see if the X pathogen is creating other reactions in the trees, besides the characteristic fruit symptom, upon which a simple detection tool could be built. In other phytoplasma-driven diseases, such as citrus greening, research shows that the tree response in trying to limit the pathogen’s spread results in the tree restricting its own sugar movement, so starches build up in the leaves instead of being transported to the fruit. Led by associate professor of horticulture Kelsey Galimba of Oregon State University, the research team will see if leaf starch levels can similarly indicate X disease infection in sweet cherry and, if so, how rapid-sensing approaches such as imaging could be used to detect the starch levels.

Studying the infection progression of LCD pathogens in young trees: Nursery trees cannot be scouted for little cherry disease symptoms because they are too young to bear fruit. This project, led by WSU pathologist Scott Harper, will look at the progression of all the known LCD pathogens in young trees in a contained greenhouse to observe how the disease progresses and how long it takes a young tree to go from initial infection to source of inoculum, ultimately offering more insight into the risk young trees pose.

Developing a leafhopper degree-day spray program for cherry IPM: Degree-day models are an important tool orchardists use to optimize spray timing for many pests, getting the best efficacy out of insecticides while reducing costs. This project, led by WSU entomologist Louis Nottingham, will develop models to target the more susceptible juvenile life stages and conduct insecticide trials to correspond with spray timing recommendations.

Dispersive distance of cherry X disease vector leafhoppers in cherry: Little is known about how far the leafhopper vectors that transmit X disease travel through orchards and surrounding landscapes. With a wide variety of host plants, understanding their movements can help design better control programs, so OSU entomologist Chris Adams will lead a project to mark, release and recapture leafhoppers. Two approaches for tagging the insects and testing them when recaptured on sticky cards will be tested.

Experimental orchard for X disease and little cherry disease research: Researchers need infected trees for these projects, and many others, but growers need to remove infected trees as soon as possible for the ongoing health of their orchards. The U.S. Department of Agriculture will host a new research orchard on experimental farmland near Moxee, Washington, more than 5 miles from any commercial cherry production. The site was historically planted with cherries, but new trees (Bing on Gisela 5 or 6, depending on availability) will be planted and irrigation lines repaired.

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment