Cherry growers want to put 2023 in the rearview mirror.

But last season’s management set the stage for this year’s crop, said Matt Whiting, a Washington State University tree fruit physiologist. And a tough market reminds growers about the importance of crop load management.

“If there’s ever a hard year, and this was an exceptionally difficult year, the only fruit that will ever make it (in a box) are the best,” he said in an interview with Good Fruit Grower. Good crop load management will shift more of the overall crop into the highest quality categories.

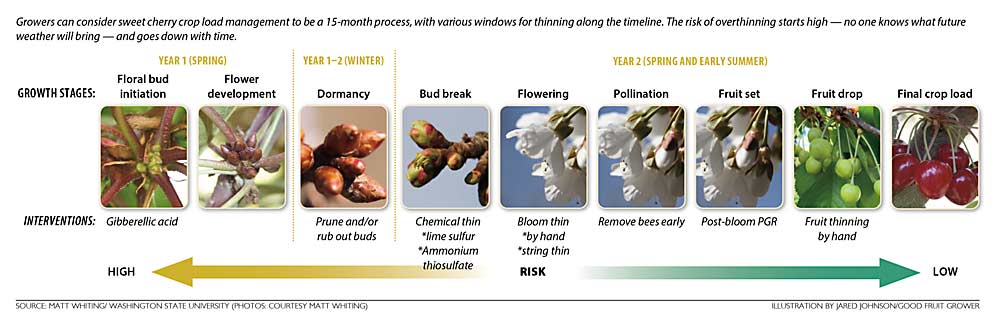

Over the past several years, Whiting encouraged growers to view crop load management as a 15-month process: from spring floral bud initiation to winter dormancy to spring bloom to midsummer harvest. Along the way, growers have tools to intervene.

“These are things you can do,” Whiting said during a talk at the Cherry Institute in Yakima in January.

It starts in spring

While the current year’s crop of cherries hangs green and pits begin to harden, the tree starts to form buds for the following year, determining then how many buds per spur and flowers per bud it will produce.

The only option at this time is to spray gibberellic acid, or GA, which can inhibit floral bud initiation. GA3 is most common in cherries. In Whiting’s trials, more and early applications of GA meant fewer flowers the following year.

It’s risky, though. A lot can happen between this stage and the following harvest — an especially cold winter, late spring frost, poor pollination weather — that would also reduce flowers. Whiting suggests using GA in a block that tends to overset each year, especially ones with a late-harvesting cultivar.

The next intervention point would be during winter dormancy. Pruning away flowering sites is the simplest and most effective crop load management activity, though the risk is still high at this point.

Spring again

The second spring is when growers think about the current crop’s fruit set, which is hard to predict.

In the mid-2000s, the rise of precocious Gisela and Krymsk rootstocks introduced more oversetting. Borrowing a page from the apple playbook, growers started chemical thinning. Whiting conducted trials, reducing fruit set from 65 percent of the flowers to 45 percent, skewing more of his fruit above a 9.5 row size.

Chemical thinners work predictably, Whiting said. The problem is no one knows what the “normal” starting point is in cherry pollination.

If chemical thinning removes 20 of every 100 flowers, great. But if the starting point is 50 flowers, removing 20 might be too many.

“That summarizes the agony of chemical bloom thinning,” he said.

Bud thinning — physically removing buds from spurs — is a reliable option, but it’s labor intensive and expensive. The best time is early, about side green, leaving two or three buds per spur, he said.

Some growers use handheld string thinners, because they’re efficient and selective. Tractor-mounted Darwin string thinners have caught on less in the Northwest, Whiting said.

Some growers simply remove bees early, after they witness a lot of bee activity during favorable conditions. He suggests more growers try this. The last flowers to open are usually runts anyway, Whiting said.

Post-bloom

Whiting and his team are spending most of their research time lately on post-bloom thinning with plant growth regulators, such as Ethephon 2 and Accede (1-aminocyclopropanecarboxylic acid, or ACC). After one year of trials funded by the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission, both seem to work. He plans to continue that research and is looking for collaborating growers with heavy-setting blocks.

The last option is to fruit thin, usually during Stage 3 growth. He has seen some growers use a rake with spider-like tines. Foothills Irrigation, a hardware store in Cowiche, Washington, sells attachments for PVC pipes.

Whiting also encourages growers to collect data from their orchards. Start with fruit set, he said. Tag some branches, count the flowers and later count fruit. Compare that with previous years. Put an intern on it.

“You’re all farmer scientists in a sense,” he said. “You’re collecting anecdotal, observational data all the time.”

Growers share

Crop load management techniques would have helped only so much in 2023, said Zillah, Washington, grower Mark Hanrahan.

“That was bad luck,” he said.

His favorite crop load management technique is aggressive pruning, especially on his Lapins on Gisela rootstocks, both known for producing a lot of buds.

He applies GA on dark sweet cherries on Gisela roots to inhibit floral bud initiation, like Whiting said, and to delay harvest for the late variety. He also hand thins blossoms at popcorn stage, either hiring a pollen company or with his own crews.

The tough cherry market of 2023 prompted Olsen Bros. Ranches near Benton City, Washington, to prune more aggressively this winter, especially on its precocious blocks of Santina and Black Pearl cultivars on Gisela in planar UFO systems.

“We are working harder to ensure we have big fruit,” said Keith Oliver, orchard manager.

While crews pruned in February, they also used their hands to rub excess buds off the tree branches at growth rings in blocks that can set excessively. Those measures should cut down yields and increase fruit size, Oliver said.

Later in the spring, Olsen Bros. sometimes lets pollen companies blossom thin in high-setting blocks.

The company last used handheld string thinners at bloom in a Santina block in 2018, the year after another large cherry harvest with too much small fruit. Oliver plans to keep that card in his “back pocket” if he needs it later in the spring.

Olsen Bros. applies GA at straw color to increase cherry hang time for the current crop but not to inhibit buds for the following year.

These techniques are not new, Oliver said, but his team feels extra pressure to improve execution after the 2023 crop.

“It’s the same old thing, we’re just trying to perfect it,” he said.

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment