With most of its acres planted in Bartletts, Smith Orchards in Wapato, Washington, stands as an uncommon reminder of what was once common. On land farmed by the Smith family since the 1930s, they grow and harvest 36 acres of Bartlett pears, with some Packhams mixed in and 2 acres of Anjous. They also have 4 acres of Bing cherries.

There are no trellises here, or plans for them.

The same crew comes back each season to prune and harvest.

It’s a small family farm, but the family doing the farming didn’t originally plan it this way.

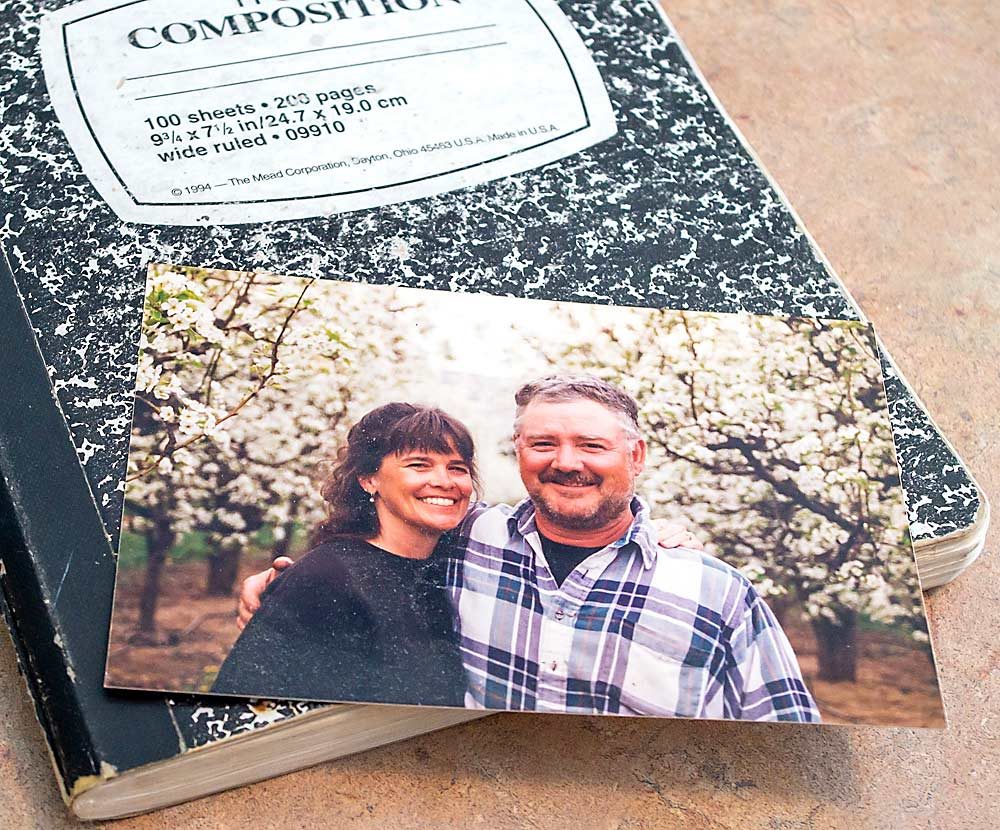

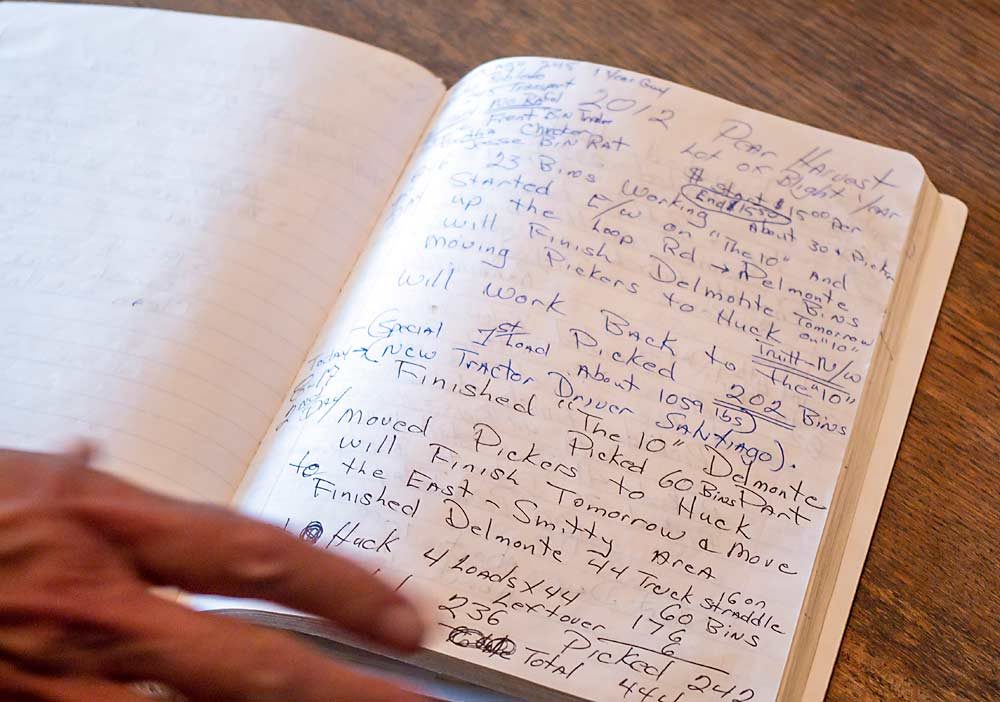

Steve and Camille Smith farmed the property together from 1991 to 2014. When Steve died unexpectedly in February 2014, he left a huge void for his wife to fill. He also left a daughter and son-in-law who wanted to help preserve the family farm and a stack of farm journals that would guide his family as they tried to figure out how to go forward.

“Most people thought I was going to sell,” Camille Smith said. “And then they thought I was going to lease, and I didn’t. I just said, ‘I’m going to do this.’”

Grateful for the help offered by neighboring growers, Smith farmed the property mostly on her own the first year. Mowing morphed into therapy as she considered her future on the farm. “I had some very good neighbors that helped me, particularly the Doorninks and the Wertenbergers,” Smith said.

That fall, Steve’s daughter, Shara Green, and her husband, Jabin Green, moved from the Seattle area to the farm in Wapato, intent on helping Smith continue to operate Smith Orchards.

Today, Smith and Jabin Green are combining a lifetime of farming know-how with a fresh research-based perspective, to embody what they call the art and science of farming.

“He’s the science, I’m the art,” Smith said with a laugh.

Different backgrounds, common goal

Smith was raised in a farming family and recalls her grandfather’s Yakima pear orchard, where they picked pears into wooden boxes on a sled pulled by the farm’s two draft horses. One early morning when she was 13, her father, an entomologist, took her to a pear orchard, explained how to pick the fruit, and said he’d be back to get her about 4 p.m. That was her introduction to harvest work, and she’s worked in agriculture ever since.

She was the first woman elected to the board for Snokist Growers, serving from 2000 to 2005, and she currently serves on the Washington Cherry Marketing Committee.

Green grew up in Portland, Oregon, and earned a bachelor’s degree in cellular and molecular biology from Western Washington University. Before relocating to Wapato, he worked as a project manager at the Allen Institute for Brain Science in Seattle. Green says he’s moved from an indoor lab to an outdoor lab as he learns how to successfully operate a farm.

“Everybody has their own method of doing things, and fortunately farmers love to talk so they’re always willing to tell me what they’re doing and why,” Green said.

One of those talkative farmers is Phil Doornink, who farms a neighboring property across from Smith Orchards.

Doornink and his wife grew up with Shara Green and they understand the many challenges of working on a multigenerational family farm. Sometimes, he said, the biggest challenges have more to do with the personalities than with the operations.

“With Jabin being new to the industry, it allows Camille to teach him without him having his own ideas about how to do things,” Doornink said. “Jabin has a great mentor and teacher (in Camille), and he brings a lot of phenomenal ideas to the farm and to our community.”

Both families get together weekly to talk about what’s happening in the orchards. “We’re a community and we help each other out,” Doornink said. “That’s the thing that’s keeping these small family farms together.”

Farming into the future

While Smith and Green acknowledge much of their operation remains “old school,” science and modernization have always had a place there. The orchard was an early trial site for codling moth mating disruption in 1995.

Last year, with a matching grant from the South Yakima Conservation District, they installed a new irrigation system in their oldest block. Recordkeeping for food safety audits and organic inspections is also now a big part of their routine.

“Farming isn’t as fun as it used to be because of all of the rules and regulations. Some of the (small growers) just said, ‘Global GAP? I’m not doing that,’ and they sold,” Smith said. “But I love to farm, and I want to keep doing it.”

Green shares Smith’s enthusiasm and embraces the opportunity to learn a new industry. He attended his first pear research review this year.

“It’s nice to know, as you see all these pear orchards disappearing for the trendier apples and new cherries, that people are still putting effort into improving the pear industry,” Green said.

Despite the gloomy forecast for the canned pear industry, they have no plans to change course.

“I think there will always be canned pears,” Smith said. “I could be totally wrong on that, but I’m not planning on pulling my pears out.”

In fact, they raised some eyebrows when they planted 100 new Bartlett trees in 2018, interplanting them in an old block. They plan to interplant another 50 Bartletts in 2020.

That devotion to the orchard’s traditional crop is balanced with a careful consideration of trends and opportunities to keep the farm viable.

“I try to research everything we do,” Green said. “It’s just habit from being in research science.” His research tells him that cider may be a good business to get into.

“The cider industry has been going strong for about 10 years now, and it’s not slowing down,” he said. “Considering some of the complications with the pear industry this year, it might be good to have something else, a little diversification.”

On fallow ground at Smith Orchards, he’s currently trialing several different cider apples. “There’s an inexhaustible list of potentials,” he said. “Some things just won’t have a chance in our climate and other things unexpectedly thrive.”

Green’s cider experience dates back to 2013, when he consulted for a cidery in Woodinville, Washington, and sold two of his cider recipes. He has also experimented with some pear and apple blends and sees potential for perry — an alcoholic beverage made from fermented pears — to be the next cutting-edge offering.

“Same thing as cider, just a different fruit,” Green said. “Maybe that’s a place that a pear farmer could start looking for future success.”

Smith also sees opportunities for the farm and is happy with the direction they’re going as Green continues to get a feel for the farm.

“When you farm, you come up with all sorts of ideas,” Smith said. “You gotta roll with the change … because it changes frequently.”

When their farm tractor caught fire in March, Smith found a rebuilt tractor, but it didn’t have auxiliary hydraulics on the back. She asked if the seller could add hydraulics but was told that couldn’t be done.

“So, I said, ‘My tractor is just sitting up there and the back end is just fine. Can’t you take the back end off that one and put it on this one?’ And within five days I had a tractor.”

They call it Massey-Fergenstein, and it’s one more example of what they’re able to accomplish by fitting together different pieces and moving forward. •

—by Jonelle Mejica

Loved this human interest piece! And to have a neighbor like a Doornink is just perfection. Camille joined our Master Gardener program this winter and is already diving into the experience. It will be fun getting to know and work with her.

Loved the story of this family farm. Thank you for being a sponsor for our 2021 MG conference. (MG’s of Kittitas County)