A young Geneva 41 rootstock grows in September at Helios Nursery in McMinnville, Oregon. Nursery owner Tye Fleming tells growers the G.41 is productive and resistant to fire blight but can struggle with transplant. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

Nurseries don’t have a single, best rootstock for all orchards any more than a mechanic has a single, best tool for all repairs. The tree fruit industry needs to stop thinking that way, said Tye Fleming, owner of Helios Nursery.

“It’s about matching the rootstock to the need that we have at that particular time,” he told growers at December’s Washington State Tree Fruit Association Annual Meeting in Kennewick.

With that, Fleming ran down a list of good and bad qualities of eight different rootstocks in a fast-paced talk.

The overall gist is that genetics from the relatively new Geneva rootstock collection give growers more choices, the way cultivar genetics have opened the door to a new array of varieties for the marketplace. Gone are the days of using Malling 9 rootstocks as the crescent wrench of the fruit industry.

“We’ve been using M.9 successfully, but we need to do better,” he said.

Young Geneva 41 rootstock propagated at Helios Nursery in McMinnville, Oregon, on September 15, 2016. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

M.9 rootstocks produce well in layer bed production, grow well in nurseries and transplant well into orchards, he said. But they are susceptible to replant disease, woolly aphids, fire blight and winter injury — problems the industry used to just accept.

“Well, we don’t have to accept those because we have new genetics coming down the road,” he said.

Enter the Geneva rootstocks — G.11, G.41, G.214, G.935, G.210, G.969 and G.890 — released by Cornell University breeders, which give growers a colorful, if confusing at times, palette of choices.

“It has taken 15 years to get to this point, and 10 years to commercialize the few of the 28 Geneva (roots) that have been evaluated by the industry,” said Tom Auvil of North American Plants and a former program manager for the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission. “The next five years will see even more focus and perhaps five more new Geneva rootstocks released.”

Each of the seven commercially available Geneva rootstocks have their own list of pros and cons, which Fleming detailed in his speech.

Here are a few highlights:

—G.11 is productive and somewhat resistant to fire blight, but is susceptible to woolly aphids and runts out in poor soils.

—G.41 is productive and resistant to fire blight, woolly aphid and replant disease with good cold tolerance but does not put out new roots, breaks roots easily, can have brittle graft unions with certain varieties and can struggle with transplant.

—G.935 propagates well, produces good crops and resists fire blight. It can feasibly be cropped in its second leaf, too. One grower made $900 per bin on a second leaf Honeycrisp, Fleming said. But the root has been sensitive to a mysterious condition that may be a combination of viruses when paired with certain cultivars. Research into that problem is underway.

—G.969 and G.890 seem like a silver bullets at first glance. They’re easy to propagate, productive and resistant to fire blight, replant problems and woolly aphids. However, G.890 may be too vigorous for some situations, and nurseries have little data about the G.969’s vigor and cold hardiness.

The challenge for nurseries is to improve on the quality of all the rootstocks to give growers the right tools even if some of them are hard to work with, Fleming said. The nurseries only have trees two years; growers have them 20.

“It’s not about being easy,” Fleming said. “We’ve got to get the right genetics to the grower so the grower can be successful.”

In the meantime, he encourages growers to consult with their nurseries to make the best rootstock choices and to even run a few of their own trials.

“They also need to be at least playing with the different rootstocks to see how they perform in their location and with their farming style,” Fleming said in a follow-up interview with Good Fruit Grower. •

—by Ross Courtney

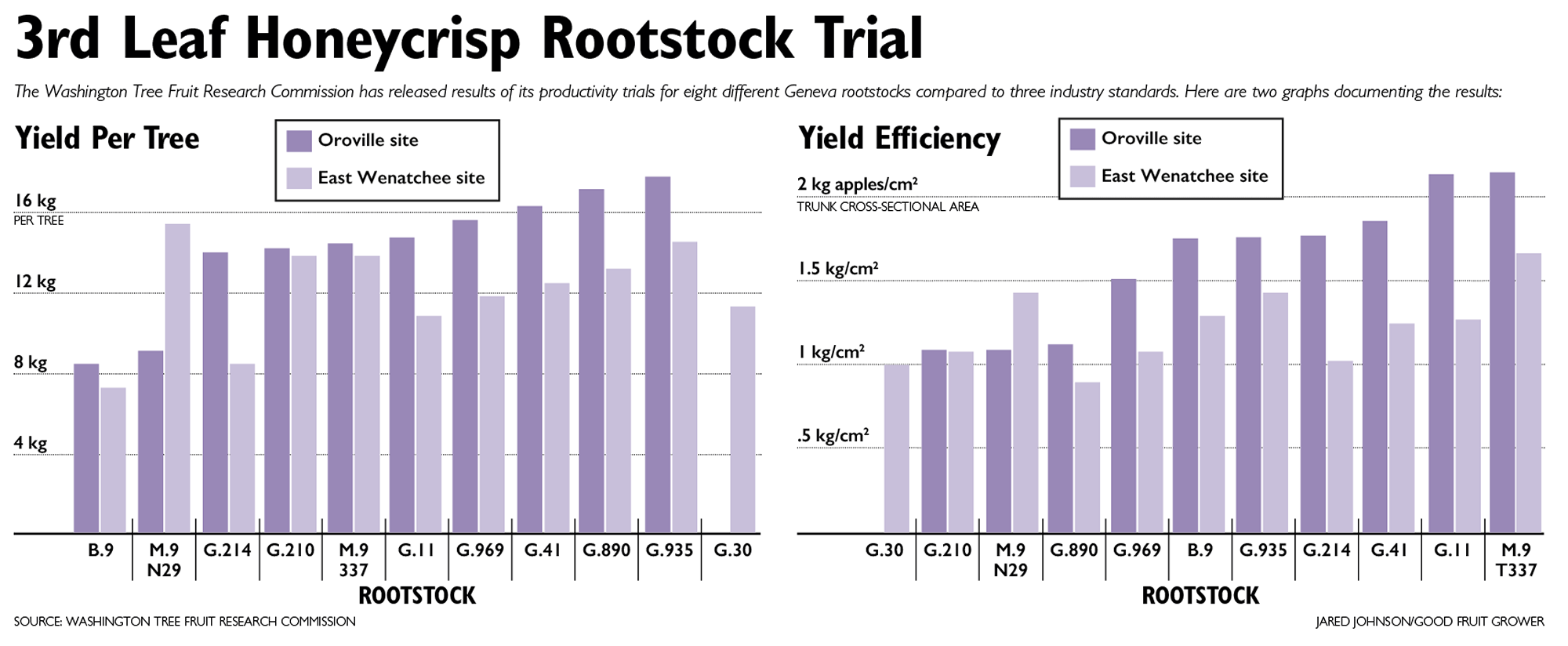

Rootstock trial

The Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission has released results of its productivity trials for eight different Geneva rootstocks compared to three industry standards. Here are two graphs documenting the results. (Source: Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission. Graphic by Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower)

Leave A Comment