A row of tall spindle trees is dead after invasion by black stem borers. (Courtesy Deb Breth)

Entomologists are trying to help fruit growers as they face another trunk-boring insect, the black stem borer. It’s been killing trees, enough to cause worry that a bigger outbreak may be coming.

Right now, controlling it is difficult, so the interim advice is, watch out for it and remove infested trees from the orchard and burn them.

“We don’t know how to control it yet,” said Cornell University entomologist Art Agnello. “We don’t know why they’ve recently come to apples.”

Affected trees seem to be those under stress, especially those enduring wet conditions and waterlogged soils or suffering from winter injury or fire blight.

The insect is attracted to trees that give off ethyl alcohol—which trees do as a reaction to stress.

Once in an orchard, the insects seem willing to attack healthy trees as well, though they may be focusing on trees that appear healthy but have been stressed by the hard winters of the last two years.

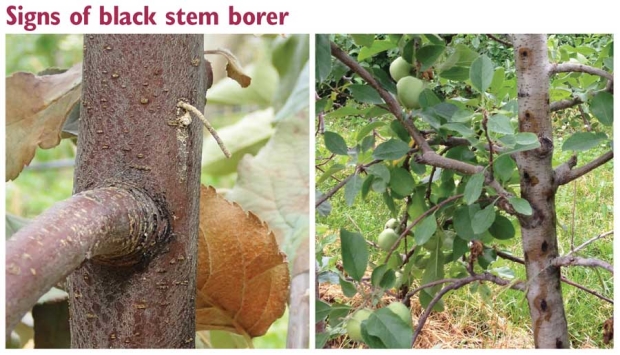

Unlike other borers that aim their attack at the base of tree trunks, black stem borers make a line of holes up the trunk. They seem to like small diameter tall spindle or super spindle trees.

Agnello, and several others, spoke to growers who were visiting orchards at Cherry Lawn Farms, owned by Todd and Ted Furber near Sodus, New York.

Visitors were there on the Lake Ontario Summer Tour to look at newly installed wind machines, but they were able to look at a few trees infested with black stem borer and hear experts talk about trials they are conducting in cooperation with the Furbers.

University and U.S. Department of Agriculture entomologists across the country are watching the pest.

It’s been found in apple orchards in New York, Michigan, Ohio, and North Carolina, but it invades other trees as well and is a serious threat to ornamental trees. It has also been found in Oregon.

Growing menace?

The black stem borer beetle is tiny, about 2 millimeters long. (Courtesy Maja Jurc, University of Ljublijana)

The insect, Xylosandrus germanus, is a tiny black beetle, about 2 millimeters long, that originated in Asia and has been in the United States since 1932.

Researchers are concerned about the recent spate of reports from apple orchards. The pest is apparently quite common in wooded areas, where it lives on weak and dying trees.

There are millions of dead ash trees in the Northeast now—an estimated 30 million in Michigan alone—killed in the last few years by emerald ash borer.

In 2013, the pest was detected in six orchards in the Lake Ontario fruit region in New York.

More infested sites were found in 2014 and, this summer, it was found in a Pink Lady orchard in the eastern New York growing region in the Hudson River Valley. It has now been found in more than 30 orchards in New York.

This year, Agnello received a grant to monitor and test control in established orchards. Deb Breth, the program leader in the Lake Ontario Fruit Program, has a grant to monitor and test controls in apple nurseries.

Agnello, Breth, and Elizabeth Tee (Lake Ontario Fruit Program aide), as well as cooperating consultants, are using a plastic bottle trap baited with ethanol to capture adults and monitor flight activity across the state.

Cornell plant pathologist Kerik Cox is working to identify pathogenic fungi and bacteria associated with the beetle, which may be the real killer of infected trees. USDA researchers Louella Castrillo and John Vandenberg are also involved, looking for biological control agents and better traps.

Insecticides labeled against tree borer species may be used, but applications must be closely timed with beetle attacks or made repeatedly or have long residual activity, Breth said. Previous research done by USDA researcher Christopher Ranger shows that systemic insecticides do not work.

Interesting biology

A foundress borer blocks the tunnel and dies while her brood develop in a chamber lined with a fungus she carried in to feed them. (Courtesy Liz Tee)

The black stem borer larvae don’t feed on the tree but on a symbiotic fungus, Ambrosiella hartigii, which the mother beetle, called the foundress, carries with her to line the chamber in the sapwood or heartwood inside the 1-millimeter (1/25-inch) diameter hole she bores into the tree. She hollows out a channel in which to lay eggs.

After she has filled the chamber with eggs (about 18) and the fungal food source is adequate for the brood, she backs out and dies, leaving her body to plug the hole. “Therefore, we can’t evaluate treatments by counting dead borers,” Breth said.

Inside the chamber, eggs hatch into larvae that develop into about ten females for every male. It takes about 30 days for the insect to develop from egg to adult in optimal conditions but typically longer under natural conditions.

The flightless males mate with the females, which leave the chamber to become new foundresses.

There are two generations per year, with the last generation overwintering as adults in galleries at the base of infested trees.

“In late summer, the beetles migrate to a hole lower on the trunk to overwinter—as many as 100 in one chamber. The beetles go into diapause and are not active again until the next spring,” Breth said.

Females emerge to infest new sites starting in late April, after two or three days with temperatures above 68°F. In 2014, activity began about May 13, and peak emergence occurred June 11, Agnello said. The first generation of adults emerged July 9-23 and the second August 20, but activity continued through September 16. This year, first flight activity was noted about May 5, with a peak at the beginning of June.

Monitoring

Left, a toothpick-size thread of frass, made up of compacted sawdust from the bore hole, is a sure sign of borer activity. (Courtesy Liz Tee) Right, a line of bore holes climb this tall spindle tree. Holes are often discolored and oozing. (Courtesy Deb Breth)

Growers should look for toothpick-like strands of frass—made of compacted sawdust from the channels—that can be seen sticking out from infected trunks after calm, rainfree days. Bark around new holes is often discolored and blistered, but not always, and oozing sap can be seen around the holes.

Julianna Wilson, Michigan State University’s IPM coordinator, advises scouting with traps made from inverted clear plastic bottles baited using one of these three methods:

—Squirt about a quarter cup of ethanol-based hand sanitizer (unscented) into the cap end (bottom) of your trap.

—With the bottle capped, pour in a cup of cheap vodka through one of the holes made in the side of the trap.

—Purchase a ready-made ethanol lure to hang inside the trap and fill the bottom of the trap with soapy water.

Hang traps on the edge of woods next to an orchard and inside orchards, and check them weekly. Beetles are very tiny and require the use of a microscope and training to identify them correctly, she said. •

A simple trap baited with ethyl alcohol (vodka will do) can be used to detect the tiny, black insects. (Courtesy Deb Breth)

In Sri Lanka we face the same problem with xyloborus fornicates in tea Camille sinensis