A father and daughter duo in a rocky section of the Walla Walla Valley grew tired of restarting their vines after deep winter freezes.

So, Steve Robertson and his daughter, Brooke Delmas Robertson, came up with a new training system that allows them to protect their grapevines and capitalize on the heat radiating from the signature cobblestone soil of The Rocks District American Viticultural Area, a small slice of northeast Oregon carved out of the larger, surrounding Walla Walla Valley AVA.

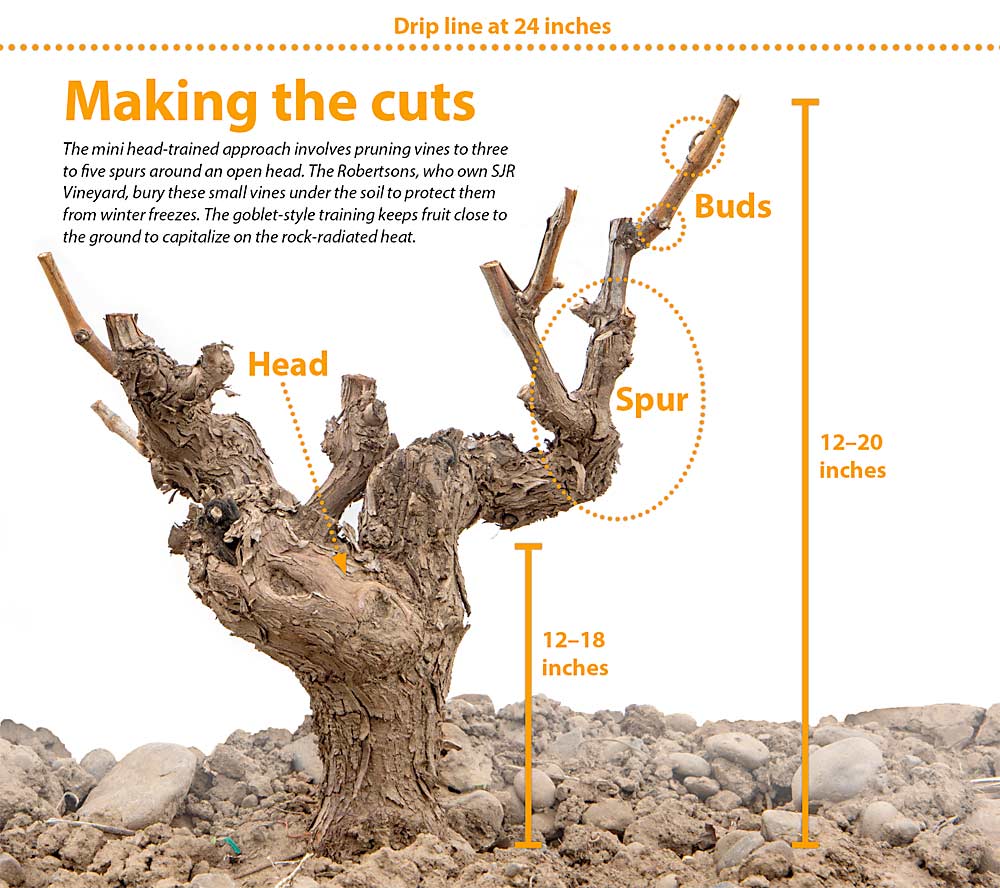

They call it mini head-trained, and it came after three deep-winter cold events between 2007 and 2017 that annihilated their buds. Each one forced them to restart training from the ground up.

“We can’t keep doing this,” they said to each other, Brooke recalled.

Aiming for world-class wines, they considered the frequent process of restructuring their vineyards unsustainable because vines would become out of balance over time.

Borrowing from a long history of head training throughout the world, Brooke came up with the idea to prune vines into the shape of a goblet between 12 and 20 inches off the ground, with two buds on each of three to five exterior spur positions — creating an open “zombie hand” shape protruding from the ground. After harvest, crews bury the head and spurs of each vine to protect it from winter damage.

Drive by the vineyard in the winter, and you will see only the dormant canes awaiting pruning poking above the surface of each vine’s covered goblet.

The low, three-dimensional wood structure keeps fruit close to the ground to capitalize on the heat radiating from the rocky soil. That allows the Robertsons to speed up ripening and ensure the fruit comes off by early October, before early freezing events.

“It has everything to do with the rocks,” Brooke said.

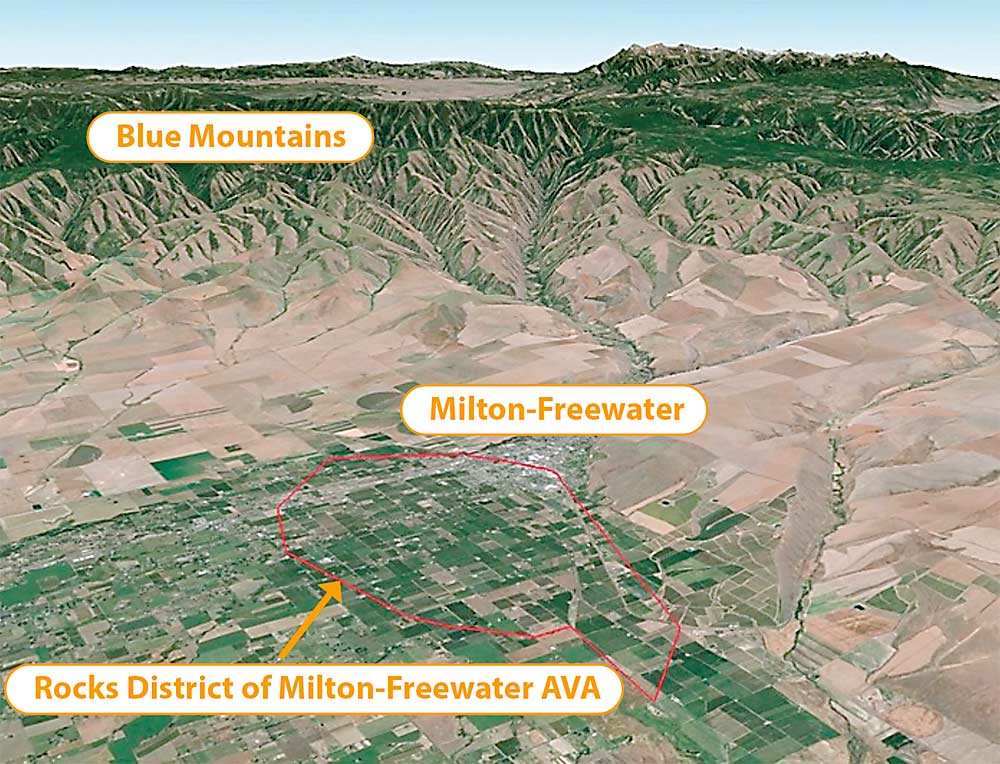

The Rocks District is a 6-square-mile section of rocky ground — hundreds of feet deep in places — created where the Walla Walla River began spreading its alluvial fan 15,000 years ago. The river carries basalt rocks from the Blue Mountains and deposits them across the district.

To irrigate, they use a drip line 24 inches high and place emitters between each vine, spaced 4 feet apart, to avoid excess moisture affecting the fruit, while roots reach deep into the rocky soil for water.

The family converted all their blocks of red varieties — Grenache, Syrah and Mourvedre — in 2017, after a winter that brought temperatures to 12 degrees below zero and caused 70 percent bud death.

As for their Viognier vines, they had always used cane burial. But after 2017, they converted from vertical shoot position to a double guyot cane-pruned system. They also lowered the head height from 32 to 28 inches to capitalize on the rock heat — just not quite as intensely as in the red varieties.

Their mini head-trained system requires expertise to prune — which they have trained crews to perform — and modified tractor-pulled plows and discsto bury in the late fall. But it requires fewer passes through the vineyard during the season. The system needs minimal leaf thinning and shoot thinning because the open structure already allows for light penetration, she said. Meanwhile, after the first two years of transition, the yields have returned to between 3 and 3.5 tons per acre, similar to what the family would get from a VSP.

The family, which makes wine under the Delmas label, started their vineyards in 2007 after Steve and his wife, Mary Delmas Robertson, moved from Napa, California.

Kevin Pogue, a geology professor at Whitman College in nearby Walla Walla, has measured the effect of the radiation on the basalt rocks, which reach surface temperatures up to 140 degrees Fahrenheit in the peak of summer.

That heat radiates back up about 2 feet high, he said, so viticulturists who want to capitalize on that typically train their trellises or fans lower. That heat radiation will speed up maturity and allow growers to harvest before the fall frosts, which the flat growing district experiences, he said. The radiant heat also dissipates quickly at night.

In the rocks, growers often skip cover cropping in the drive rows. They don’t need it, he said, at least not to prevent erosion.

“Baseball-sized cobblestones don’t blow away in the wind,” he said.

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment