(TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)” width=”900″ height=”553″> A tour of Byron Albano’s orchards in California’s Cuyama Valley in March. The orchards rest high in the Sierra Madre Mountains, across a dry riverbed leading out of Los Padres National Forest.(TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

Byron Albano is one of the southernmost apple growers on the West Coast but has a late season. He has plenty of water but no surface irrigation.

He lives in the Los Angeles suburbs but farms in a remote mountain hideaway.

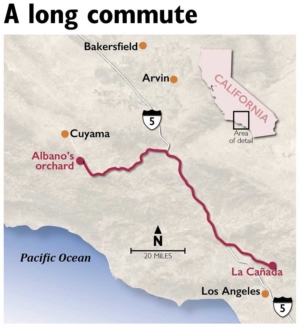

(Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower illustration)” width=”300″ height=”328″> Byron Albano drives two hours on both interstate and twisty mountainous highways from his home north of Los Angeles to reach his remote orchard in the Cuyama Valley in Southern California. From there, his packing facility is more than an hour away in Arvin, southeast of Bakersfield. (Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower illustration)

“One of the things I love out here is your cell phone doesn’t ring,” he said, surveying his family’s 316-acre Cuyama Orchards abutting the Los Padres National Forest.

Welcome to life at 3,300 feet in the Cuyama Valley, a rugged region of pinyon pine, manzanita and sagebrush that belies its proximity to metropolitan sprawl.

About 20 years ago, the Cuyama Valley was home to some 2,500 acres of apples.

His parents, Howard and Jean, also live in the Los Angeles area but spent half their days in Cuyama cutting their blocks out of the hills. Byron, now 50, helped but mostly concentrated on marketing.

Around the year 2000, the market glutted. To survive, the family sold directly to Los Angeles stores and kept planting, while others turned to carrots.

Many trees came into production from 2003 to 2007, just as the market improved.

Today, they are the only apple growers left in the Cuyama Valley, with Whole Foods and Gelson’s, a Southern California grocery chain, among their clients. They also sell to stores and farmers’ markets in the Bay Area.

The family owns a packing facility with cold storage in Arvin, near Bakersfield.

Byron Albano credits loyal customers for their survival. “That keeps us in business,” he said. “Without that, we’re not here.”

Gelson’s stocks apples from all parts of the globe but gets about 80 percent of its California apples from Cuyama Orchards, said Mark Carroll, senior director of produce.

The company’s high-end shoppers are willing to pay a little more for a combination of organic and local produce, Carroll said.

“They’re about as local as you can get in Southern California,” Carroll said.

(TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)” width=”900″ height=”600″> In Albano’s V-trellis system, he ties the leaders overhead in a hoop to help control vigor. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

Like all fruit growers, the Albanos have been converting to high-density trellised systems, choosing tall-spindle for Fuji, Pink Lady and Honeycrisp varieties.

They actually have been replacing older Honeycrisp trees with new ones, experimenting with rootstocks in blocks of 11-by-3-foot spacing. The variety is not widely grown in California.

The family also has been changing from overhead sprinkler frost control to wind machines because moisture at bloom has exacerbated fire blight problems. Blossom onset has crept from April 1 to early March in recent years.

(TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)” width=”900″ height=”557″> Moisture during bloom can be an issue in the Cuyama Valley, sometimes leading to fire blight problems. Workers mark trees that look to have fire blight before they are trimmed or removed from the block. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

They had snow a day or two before the beekeepers arrived this year.

They use organic copper sprays, lime sulfur bloom thinner and Blossom Protect, a yeast solution, as prophylactic controls.

Meanwhile, commercial heirloom varieties make up about 10 percent of their acreage, and they have 500 trees of other heirloom varieties in a test block. They also grow a few rows of pears and even a little hay.

Characteristics of growing area

(TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)” width=”900″ height=”600″> At 3,300 feet, the orchard’s high altitude has a later season than most of California and produces crops around the same time as Washington’s Yakima Valley. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

Bountiful water is one of Albano’s fortunate geographical quirks. Spring flooding aside, the Cuyama River runs dry a lot of the year, but his farm sits atop an alluvial aquifer.

The southern latitude provides warm days and the elevation cool nights, giving him a harvest window similar to Washington’s Yakima Valley. The rest of California picks much earlier.

Albano has no neighbors, unless you count the occasional illicit marijuana grower in the surrounding hills.

So, he doesn’t have to worry about somebody else’s spray drift, but he also has no one with whom to compare notes. University extension staff focus on the larger apple growing region near Lodi.

(TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)” width=”900″ height=”564″> Marcel Emea repairs a seal on an irrigation pump. The orchards rely on pumped irrigation because the remote location lacks a canal system. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

Albano attends industry workshops and conferences and even hosted an International Fruit Tree Association tour in 2008. His father, Howard, is a past IFTA board member.

Albano has faced little pressure from codling moth. His pheromone disruption keeps the pests almost nonexistent, he said.

He has not seen the brown marmorated stink bug in the orchard, but he knows it has reached Los Angeles. He’s afraid it’s going to hitchhike one day on his commute.

That’s a two-hour commute, by the way, which he makes two or three days a week. Albano lives in La Cañada on the outskirts of Pasadena with his wife and three children.

This year, he has taken on the bulk of farm management, as well as his marketing work, due to his parents’ ages — both are in their 80s.

Four of his 50 year-round employees already live on the farm, and he plans to recruit an on-site farm manager next year so he can focus more on business management and sales.

(TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)” width=”900″ height=”595″> Byron Albano says loyal customers keep him in business. “Without that, we’re not here,” he said. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

Still, Albano enjoys spending time on his family’s orchard, occasionally scrambling up a nearby hill for a bird’s-eye view.

“Frankly, it’s really unbelievable, I think, to me that my father was able to scratch a living out of this location with apples and that we’ve survived and actually thrived.” •

– by Ross Courtney and photos by TJ Mullinax

Need pipins !