Splitting in Concord grapes is more common following drought stress, according to researchers at Washington State University’s Irrigated Agriculture Research and Extension Center in Prosser, Washington. (Courtesy Washington State University Viticulture and Enology)

When Ben-Min Chang came to Washington State University’s Irrigated Agriculture Research and Extension Center in Prosser to pursue his doctorate in viticulture, he was interested in studying berry splitting. It’s a problem in his native Taiwan, but he figured Washington’s dry climate would provide the perfect “control” conditions with no splitting.

Instead, he found that drought stress actually plays a key role in susceptibility to splitting, surprising since the issue is associated with an abundance of water.

“Most people don’t think we have splitting issues, because we have such a dry climate,” said Chang, now a postdoctoral researcher working with viticulture professor Markus Keller. “But we found this is not the case. We do have some splitting and it’s quite a complex issue.”

In Washington’s dry climate, split berries tend to quickly dehydrate. That means growers may mistake splitting as shriveling. “It just looks like a raisin instead of a wine grape,” Chang said. That can impact yield, and splits can also encourage pathogens such as botrytis or sour rot, especially in compact-cluster cultivars.

His research includes measuring splitting resistance in Merlot, Syrah, Zinfandel and Concord grapes; understanding the physiology of splitting; and looking at the role of water stress in the incidence of splitting in a Concord vineyard.

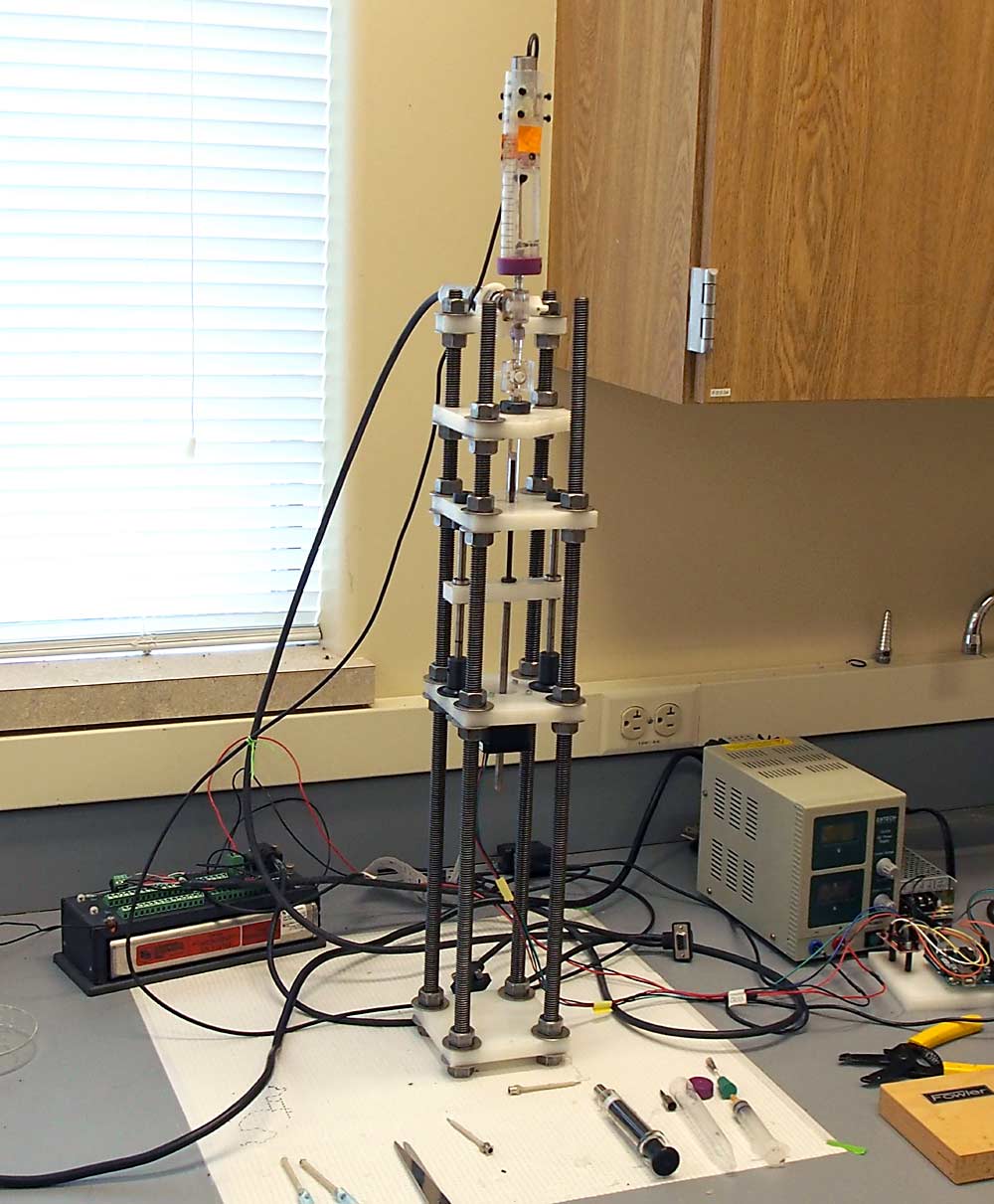

Researcher Ben-Min Chang used this device to measure the internal pressure necessary to split different grape cultivars. It turns out that Merlot has a much higher resistance than more cultivars, Chang said. (Courtesy Ben-Min Chang)

The deficit irrigation study showed that preveraison drought seems to induce splitting later in the season when normal irrigation levels resume after veraison, he said. Maintaining the drought condition all season results in similarly low splitting risk compared to maintaining full irrigation all season.

“If the berry dehydrates, it will shrivel, and it will create ripples on the skin and that may be the trigger that creates a flaw,” Chang said. “That’s my hypothesis, anyway.”

The physiology of splitting is clear: As water moves into the fruit after heavy rainfall, it increases the pressure on the skin. Using a pressure sensor and a pump to increase the berry’s internal pressure, Chang charted resistance across the fruit’s development and found that berries become much more susceptible to these changes in pressure as they begin to ripen.

He also found that Merlot is much more resistant to splits than the other cultivars because it has more layers under the cuticle, which provide support. Concords have a thicker cuticle, but less supportive structure underneath, Chang said.

Now, he’s exploring what could be done to improve cultivar resistance, including looking at enzymes that appear to harden the cell walls below the cuticle.

Interest in the splitting issue is on the rise, Chang said. In 2018, Malbec growers in the Yakima Valley found significant splitting after a couple of high-humidity nights allowed water to condense on the fruit surface.

“That was enough to trigger splitting in Malbec specifically,” Chang said. Looking at Malbec berries closely, they found the fruit tends to have micro cracks around the style that both allow water in and act as the weak point that starts the split, he said. •

—by Kate Prengaman

in STYLE are you referring to the point of attachment to the stalk (peduncle) where the micro cracks occur or at the distal end of the berry where the stigma heals over?