Glenn Proctor, Ciatti Company, told attendees of the 2018 Washington Winegrowers Convention that luxury wine sales in the US are decelerating and will grow at a slower pace in the near future, in Kennewick, Washington, on February 7, 2018. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

The growth in the premium wine market has been a boon to the Washington wine industry, as American consumers seem increasingly willing to spend more for wines marketed by variety, vineyard and terroir.

But a new trend — branded wines that speak to consumer’s identity, eschewing cultivars and AVAs and other traditional markers of authenticity — is now gaining traction in the lower end of the premium market, said Mike Veseth, author and editor of the Wine Economist blog.

Think winemaker Charles Smith’s success with Kung Fu Girl Riesling or the 19 Crimes brand, whose sensory profile and outlaw vibe target millennial men with bottles priced in the $12 to $20 range.

Mike Veseth

“It’s everything that shouldn’t sell in American today,” Veseth said of the Australian, Shiraz-based blends named after the crimes that could get you sent to the former penal colony. “Who would have thought you could sell a million cases of wine with a picture of a sad British man on the label?”

This battle between “land” and “brand” based marketing could create new opportunities for Washington state wines, he said in a session on industry trends at the Washington Winegrowers annual convention in Kennewick, Washington, in February. That’s important as growth in the premium wine market that fueled the expansion of the state’s industry appears to be slowing.

“We’re moving into a new plateau, where the premiumization growth will slow down to just about the overall market growth rate, and we’ll enter a new period where the U.S. market is just more focused on premium wine,” Veseth said.

The premium market growth, which has had economists scratching their heads, doesn’t mean that American consumers are just generally willing to spend more money on wine. They are, however, willing to pay more to try new things if the marketing is right.

“People are unwilling to pay more for the same wine, but they are willing to pay more for a different wine,” he said. “The proliferation of new wine brands in the U.S. is an intentional effort to give consumers new wines to purchase at higher prices.”

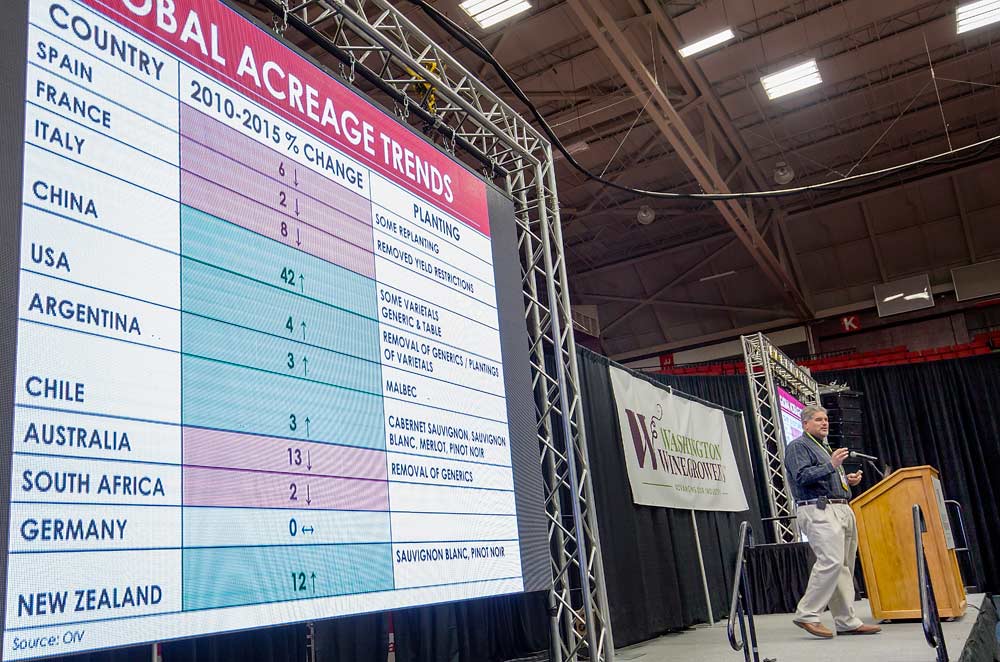

Globally, the story looks starkly different. European consumption has been on a decline and wine drinkers are increasingly price conscious. Over the past few years, growers in Spain, France and Italy ripped out vines to compensate, said Glenn Proctor, a bulk wine buyer for Ciatti Co., a global grape broker.

Consumption, worldwide, declined since a high around 2010, he said, but seems stable now. But last year, the supply side adjusted down enough to cause a very tight market, Proctor said, especially with the difficult weather in Europe and South America that reduced global yields about as much as total California production.

“2017 was the shortest crop in many years,” he told the crowd at the convention. Italy and Spain temporarily turned into net buyers, not sellers, which pushed up bulk prices significantly.

Just don’t expect that to be a long-term trend. More normal supply is expected this year in most production regions, although there is major uncertainty concerning South African production as the country faces unprecedented drought.

Growers in New Zealand are still planting more Sauvignon Blanc, and Australia’s exports to China — the one growing market — are booming.

Glenn Proctor

In California, domestic sales rose 1 percent last year, but exports fell 16 percent. Proctor attributed the decline in part to the strong dollar earlier last year and the weakened British pound.

Bulk wine imports to the U.S. were up 23 percent, while case goods rose 4 percent — driven by consumer demand for European wines such as Prosecco, Rosé and Champagne, he said.

Overall, the U.S. market appears to be balancing out.

“A year ago, sellers ran the roost, so buyers started looking for other options for supply,” Proctor said.

Now, he says it’s clear sales of luxury goods in the U.S. is decelerating, a slowdown that includes the premium wine market. Moreover, consolidation at large distributors is making it tougher to get wines in front of consumers at retail stores, and the market share of grocery chains’ own private labels is growing.

Meanwhile, it’s not getting any cheaper to grow grapes, so more wineries may start feeling a squeeze.

“What we see is wineries will continue to get bigger because you have to be competitive and hold those margins,” Proctor said. “Imports are going to continue to grow on the bulk side and on premium bottled because they are producing things like Rosé and sparkling that the consumer wants.” •

Meanwhile, in that other Washington

The dysfunction in Washington, D.C., is making it difficult for agriculture issues to gain traction, said John Aguirre, executive director of the Winegrape Growers of America, which advocates for the industry.

Progress on issues including immigration reform and guest worker programs, trade negotiations and Farm Bill funding remains slow and uncertain. One success worth celebrating: the tax reform bill passed late last year includes the Craft Beverage Modernization Act. The craft beverage legislation will ease excise taxes paid by wineries.

And despite chaos in Congress, Aguirre and other industry advocates continue to work with the Food and Drug Administration to exempt wine grapes entirely from the Food Safety Modernization Act’s Produce Safety Rule, like other produce rarely consumed raw.

“Wine grapes are not grown for the table grape market, but the FDA doesn’t get that,” Aguirre said. “They think you may decide on a whim to shift your wine grapes to the table grape or raisin grape market. But we should be treated just like potato producers and not subject to the produce safety rule.”

But the current rule does include an individual commercial processing exemption that some winegrowers may want to pursue, but it’s a paperwork hassle and the compliance details aren’t entirely clear.

Aguirre explained that to get an individual exemption, growers need to disclose to buyers, for each lot of grapes, that the fruit has not been processed to reduce the presence of microorganisms that pose a health risk, and keep documentation. Then, wineries must confirm to growers in another statement that the grapes were indeed processed into wine, he said. These records will need to be kept, for each lot of grapes, for several years.

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment