—by Matt Milkovich

Codling moth is a major pest of apples in Adams County, where most of Pennsylvania’s apples grow. For the most part, a combination of diamide insecticides, Delegate (spinetoram) and pheromone mating disruption provides adequate codling moth control for the region’s growers, but new developments are starting to complicate management.

For one thing, in a handful of the region’s orchards, codling moth has begun to demonstrate resistance to the diamide group of insecticides (which cause muscle paralysis and death in targeted insects). For another, pheromone mating disruption is not as predictable as it used to be. And finally, warmer weather might be making the pest more persistent, said Penn State University entomologist Greg Krawczyk.

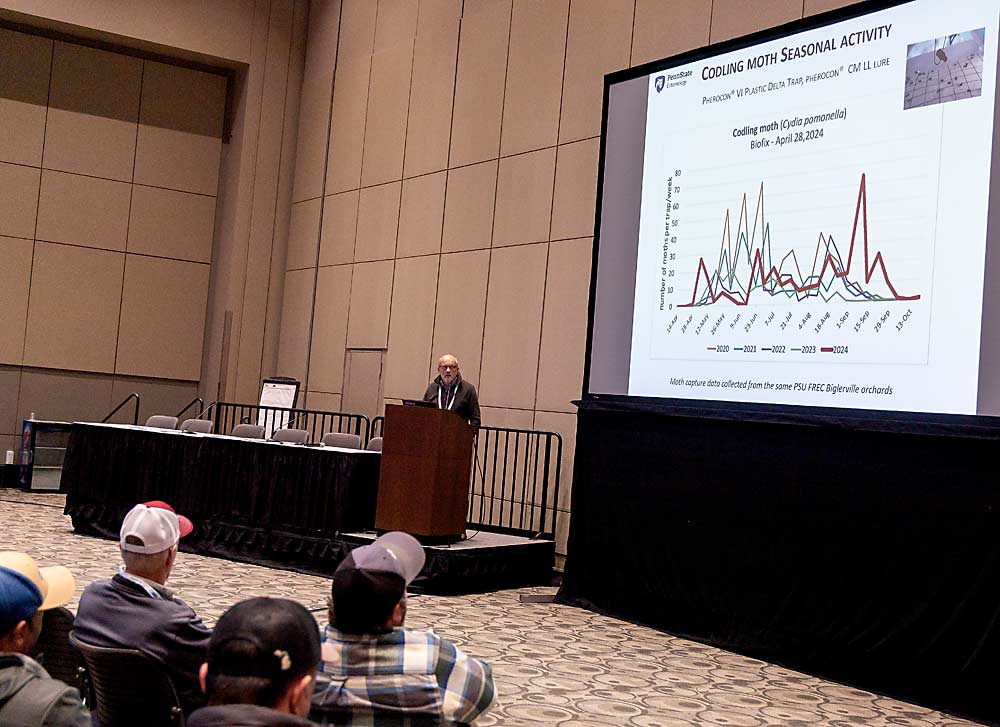

Krawczyk discussed codling moth control in Pennsylvania during the Great Lakes Fruit, Vegetable and Farm Market EXPO in December. He said Adams County typically sees two generations of codling moth per season, but 2024 was so warm there were three complete generations.

The moths started flying about two weeks earlier than normal last year and were still active in mid-October, about a month later than normal. If higher temperatures continue, an extra codling moth generation could become more common. If given enough time to develop, that extra generation could overwinter and lead to a higher population the following season, he said.

An extra generation also means more pesticide applications, which increases the risk of codling moths developing pesticide resistance. After more than 15 years of using diamide products, a few growers are starting to see application failures. Resistance isn’t widespread, but it’s a warning sign. Krawczyk encouraged growers to keep rotating insecticide groups and to not overuse one just because it works.

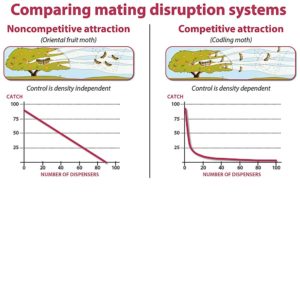

Pennsylvania growers also use mating disruption to control codling moth, suffusing entire blocks with female codling moth pheromones to confuse the males and shut down their flight. In the past several years, however, many growers have been catching male moths in their pheromone traps, which shows the males are still flying. Some growers in Eastern states outside of Pennsylvania are also catching male moths in pheromone traps. Krawczyk isn’t sure why.

“I’m trying to understand why we’re catching moths when they theoretically should not be able to find the trap,” he said.

It doesn’t necessarily mean mating disruption isn’t working, or moths are developing resistance. It might have something to do with changes in lure or trap design (see “New answers and new questions for codling moth control”), tree spacing, dispenser placement or perhaps higher temperatures, Krawczyk said.

Adams County grower David Slaybaugh told Good Fruit Grower that codling moth control is getting harder. He grows about 650 acres of apples across several locations, and in some of his orchards, codling moths have started displaying insecticide resistance.

Slaybaugh’s orchards saw a third generation of codling moth in 2023 and 2024, and he experienced pressure from the pest all season long both years. That led to extra sprays, which increases the chances of the pest developing resistance. Slaybaugh decided to try pheromone mating disruption last year, but he said it didn’t work very well. He found male moths in traps and “way too much damage” to his apples.

When asked what else he can do to control codling moth, Slaybaugh laughed. He said he hopes a new pesticide chemistry, soon to be released, could help. He also will probably try mating disruption again, but he’s not expecting much.

“We’re using everything we know to fight codling moth,” he said, but “it’s getting worse.” •

Leave A Comment