No one wants to find phylloxera in their vineyard, but growers should be strategic about scouting for the root pest to increase the confidence about whether they need to manage for it or not.

“Knowing when, where and how to scout for phylloxera is critical to properly identify if you are dealing with this challenge in your vineyard,” said Michelle Moyer, extension viticulturist for Washington State University.

Because almost all of Washington’s vineyards are planted on their own roots, as opposed to phylloxera-resistant rootstocks common globally, the discovery last year that the tiny root-feeding insect is established in several grape growing areas raised alarm. Understanding where phylloxera is lurking in vineyards will help growers prevent the spread of the pest to uninfected blocks and make plans to replant on rootstocks where that may be necessary, said WSU extension specialist Gwen Hoheisel.

“Moving soil from infested blocks to noninfected blocks can increase the risk of spread,” she said. Planning vineyard tasks, such as cultivation, in the right order can reduce risk.

Where

Symptoms can take several years to show up, because regulated deficit irrigation practices to control the canopy mask the vigor reductions caused by phylloxera root feeding, Hoheisel and Moyer said. But over time, the stress to the vines becomes more severe.

“When you can no longer control the rate at which you are reducing vigor, that’s a good indication that maybe you should check to see if something else is affecting the vineyard,” Moyer said.

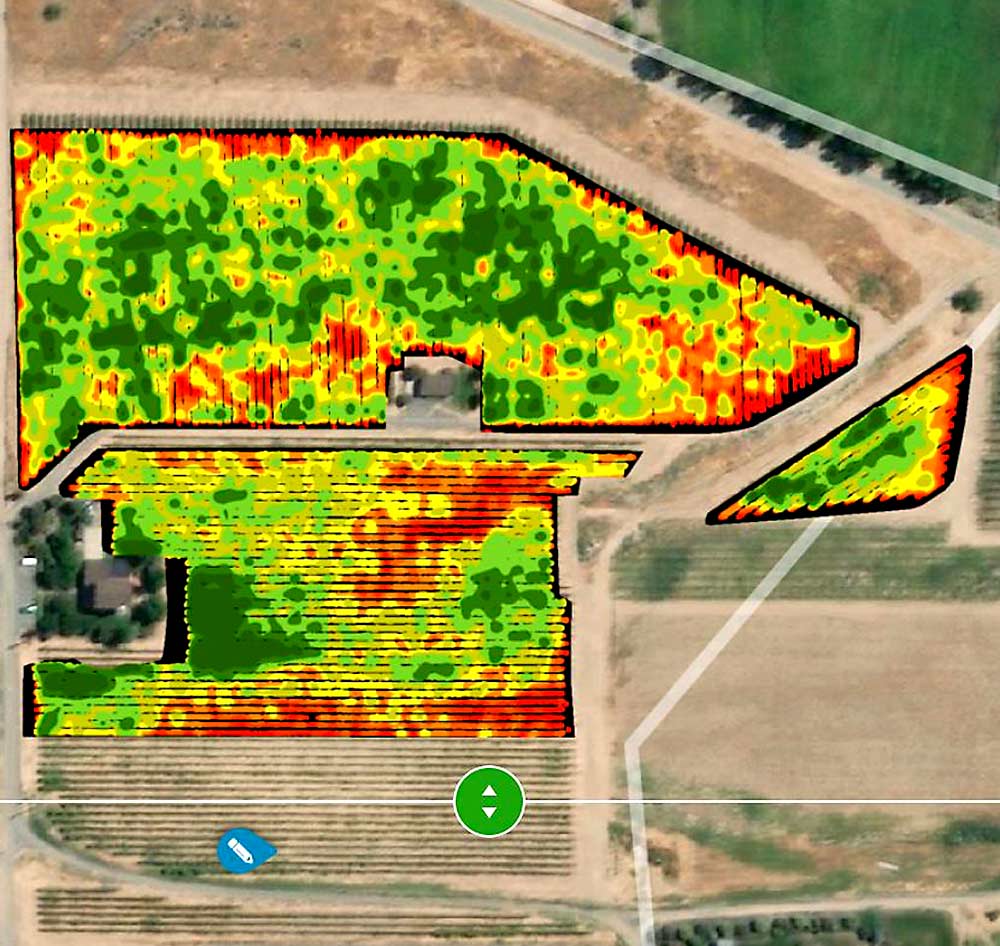

Moyer recommends using NDVI imagery to identify pockets of low vigor to scout in. Look for stunted shoots or reduced canopy growth in the row. There’s also a telltale pattern for phylloxera-caused vigor reduction, she said: an oval shape that stretches along vine rows.

“Phylloxera is a soilborne root pest, and if you do a lot of movement of equipment or soil, phylloxera will move with it,” Moyer said. Therefore, the infestation will more likely spread along rows, rather than across them.

When

Phylloxera likes moderate soil temperatures.

“If you want to improve your chances of finding active phylloxera, the best time to do it is the early spring or in the fall around harvest,” Moyer said.

When soil temperatures reach 64 degrees in the spring and shoot growth is underway enough that pockets of low vigor could be apparent, it’s worth looking. In the fall, lots of phylloxera will resume moving and feeding as soils cool down, Moyer said, and after a season of deficit irrigation, vines are starting to shut down and signs of stress should be more obvious.

How

Scouts will need a shovel, a trowel, a small pair of pruners to take root samples, flagging tape and a magnifying loop or hand lens. Hoheisel also recommended wearing plastic booties to prevent spreading the infestation via soil stuck to your boots.

For the best chance of finding phylloxera, or signs of their presence, dig in the vine row where you expect roots and clip a sample of a healthy root with fine roots.

During an active infestation, roots will form galls in response to the feeding. In fresh tissue, these appear as small, cream-colored protrusions, Moyer said. As the galls get old and dry out, they will look more like dried mouse droppings stuck to the root.

With the naked eye, you may see gold or yellow specks along the root. That’s “your telltale sign to pick up your hand lens and look for clusters of phylloxera louse,” Hoheisel said. At just 1 millimeter long, phylloxera can range in color from pale yellow to dark brown, and they can hide in crevices, she added.

If you don’t find many roots at all, or find dead roots, that’s a sign that the phylloxera infection may have been severe, but now the insects have moved on to find more healthy roots. Roots can be killed by the secondary rot organisms that take advantage of the wounds from phylloxera feeding.

“You are not going to find phylloxera on roots that have no fine roots to feed on,” Moyer said. “If symptomatic plants have a really damaged root system and don’t have any phylloxera, the best place to look is to move to healthy-looking vines up and down the row.” •

—by Kate Prengaman

Important and helpful video WSU. For all growers and producers in #wawine