Concord grapes occupy about 30,000 acres between the Lake Erie shore and the Allegany Plateau Escarpment, the high ground visible in the distance. (Richard Lehnert/Good Fruit Grower)

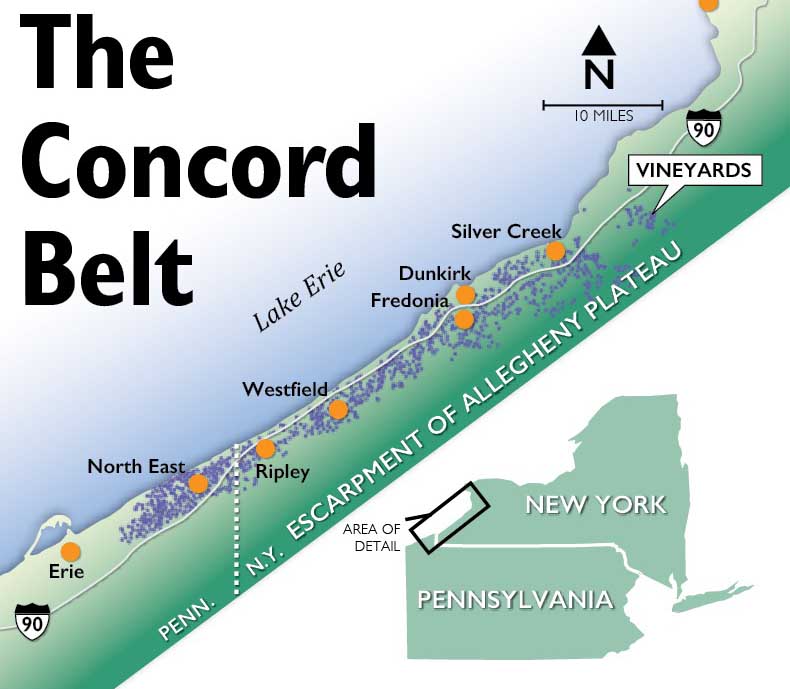

It’s called the Concord Belt, a narrow ribbon of flat land about 60 miles long and two to six miles wide, tucked between the shore of Lake Erie and the Allegheny Plateau Escarpment in western New York and northwestern Pennsylvania.

That area, with its climate moderated by the lake, is said to be the oldest Concord grape growing region in the world; it’s the largest area of grapes east of the Rocky Mountains.

The region has 525 growers with about 32,000 acres of grapes, most of them Concords and Niagara juice grapes, but with some wine grapes, making up about two-thirds of the tonnage of grapes grown in New York.

But growers in the Concord Belt are having to bore a new hole or two in their own belts and cinch them a bit tighter.

They are adjusting to a combination of poor markets and bad weather that will cause the region to contract its output by 10 percent or more, says Kevin Martin, an extension educator in financial planning and business management and part of the Lake Erie Regional Grape Program (LERGP).

“To survive a long period of lower prices, growers will need to reduce business expenditures by over $10 million dollars per year,” he said. “Growers may also need to reduce personal expenditures as income declines.”

LERGP is a joint program between New York’s Cornell University and Penn State. Martin works for Penn State.

The Concord grape is native to North America.

It was selected and propagated from wild seedlings by Ephraim Bull in Concord, Massachusetts, in 1849. Recent genetic testing shows it has some vinifera parentage, as well as lambrusca. In the 1870s, it was brought to western New York, where climate, geography, and soils proved to be very suitable to its production.

The slip-skin purple grape is also grown in the Finger Lakes region of New York, in southwestern Michigan, and in Washington State. The grape forms the base for the nation’s supply of grape juice, jam, and jelly. Washington State has fewer Concord acres (26,000), but leads the nation in volume produced.

Repeated late freezes in the spring of 2012 cost the Concord Belt growers millions of dollars. But extremely low temperatures during the last two winters have done longer-term damage, killing vines outright. Source: Lake Erie Concord Grape Belt Association (Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower illustration)

Typically, spring frosts are the biggest threat to the area’s grape industry, Martin said during a Good Fruit Grower visit to his regional research and extension station near Portland, New York, this summer.

Because the lake keeps the region cooler in spring and warmer in the fall, frosts are less likely to damage the crop. “It’s why we’re here,” Martin said.

But the last two winters have been hard ones across the Great Lakes region, putting a severe test on grapes of all kinds.

Last winter, a low temperature of -29.9°F set a record in the Concord Belt, killing some wine grape varieties, root and vine, and even taking a toll on the normally winter hardy Concords and Niagaras as well.

“We saw significant damage to vinifera and some tender hybrids and also some Niagaras,” Martin said. It was not just the extreme low temperature on one date in the winter of 2014-2015 that hurt; temperatures fell to -12° to -15°F several times during the winter before that, he said.

“Some of the vinifera were so damaged they produced no suckers and will need to be replanted—if growers choose to replant. Some have decided it is time to rethink and change,” he said.

This vineyard was killed by cold last winter. (Richard Lehnert/Good Fruit Grower)

Across the Great Lakes region generally, a 40-year warming trend—including milder winters—induced wine-grape growers into planting the less cold hardy but better-for-wine-making vinifera varieties.

Small wineries, driven by favorable changes to state laws, also helped demand for vinifera and hybrids. The last two winters have served to weed out those varieties and sites that can’t make it.

Juice in decline

But low temperatures are just half the problem in the Concord Belt. The other is low prices and a loss of buyers in the juice grape market.

The market for juice grapes has been eroding for several years as consumers backed away from high-sugar drinks and from Concord grape products like jam and jelly, Martin said. Other fruit juices have fared poorly as well. Fighting back, juice makers have come up with interesting new flavors, like cranberry-apple, but Concord juice is so intensely flavorful it overwhelms, rather than blends.

The severity of the market and weather-related disasters faced by the grape industry have been unprecedented, Martin said. Much of the trouble has come down on growers in New York’s Chautauqua County, where most of the Concord Belt is located.

“Tourism and wineries are a smaller part of the industry in the county, but their growth has been critical for industry stability,” he said. “All of this success has taken a century to build; unfortunately, short-term challenges put this economic force at risk.”

Where the market for juices had been sagging in general, economic problems got decidedly worse in the Concord Belt. In 2014, ConAgra Foods announced it had bought Carriage House and would close two of its juice and jelly product plants and move operations to Kentucky early this year. While overall this should not affect the market for bulk juice concentrate, it hurt some growers whose marketing contracts were canceled.

About the same time, soft-drink maker Cott Corporation began to cut back on Concord purchases and on marketing contracts with growers.

While the big force in the juice grape business is National Grape Cooperative, which owns Welch’s, that co-op was in no position to take on what it considers to be “new acreage” from these growers. Its own growers were suffering from low prices and weak demand.

“Before the market was entirely saturated, LERGP worked with growers to find additional markets for an estimated 3,000 tons,” Martin said.

“If these long-term trends continue, the impact will be much more significant. In addition to unmarketable crops, we will also see declining equity and land values for growers. Indirect impacts will also increase well beyond the $3.5 million dollars in lost grower sales, as these growers remain important employers and consumers in Chautauqua County.”

Martin noted that processor cancellations and price reductions are a direct result of a poorly performing juice market. “Prices of processed juice have plummeted by 60 to 75 percent in the last two years. At these prices processor margins will be razor thin, even as grape prices in 2015 remain extremely low for growers.”

Kevin Martin cites weather and poor markets as causes for consternation in the Concord Belt. At the research and extension station in Portland, New York, a support team called the Lake Erie Regional Grape Program works to help both wine and juice grape growers. (Richard Lehnert/Good Fruit Grower)

Making adjustments

Wine grape growers will have to decide whether they should switch to different varieties, since Cabernet Sauvignon and Riesling may be too sensitive to grow on most sites if cold winters persist.

Where vines died completely, growers can decide to replant to other varieties. Where suckers survived, most growers will train up new canes.

In New York, wineries can get juice from other states to continue making and selling wine, but laws prohibit buying out-of-state juice except in the event of a disaster. There are two kinds of licenses in New York, one costing more but allowing more latitude from that regulation.

Probably the safest of 32 wineries in the region are those that make and sell wine based on native varieties like Concord—the traditional sweet wines, like Manischewitz that predate the conversion to vitis vinifera and aim at a kosher clientele. There are other wineries that use other native American grape species like Catawba and Niagara.

Concord growers need to decide whether to stick through the low price period or change to something else. Martin noted that, since the advent of mechanical harvesting back in the 1970s, grower costs have been lower and, in most cases, investments have been paid for. There are about 300 grape harvesters in the region to do the harvest work.

Pruning, at 27 to 32 cents a vine and 610 or so vines per acre, is the largest production cost, about $225 an acre.

Martin figures most growers can endure Concord prices of $200 a ton—not getting much return on investment but surviving if they reduce expenses. Prices were about $240 a ton last year, but they were continuing to fall. Prices of grape juice concentrate, once as high at $25 a gallon, had fallen to $6 to $9.

In the long run, Martin doesn’t see a decline in overall grape acreage, but expects less to be harvested in the short term.

“The LERGP Extension team also provides assistance to growers looking at exiting the industry,” he said. “For some, this becomes a least bad option, especially for those who have lost contracts and have no home for their grapes.” •

– by Richard Lehnert

Leave A Comment