Yakima grower Andrew Sundquist likes to watch his apples grow — on an app as well as in the orchard.

In each of his Central Washington apple blocks, pressure sensors known as dendrometers are installed on tree trunks and around apples to detect the minute fluctuations in growth rates that can signal water stress. He uses the technology to inform irrigation scheduling.

“The idea of looking at the plant needs instead of the soil was intriguing,” Sundquist said, explaining his interest in dendrometers. Soil moisture sensors “just tell you if it’s wet or not,” he said. “It doesn’t tell you if the tree is using it.”

Two years ago, he connected with Phytech, a company that pairs dendrometers with irrigation sensors and weather data in an app that aims to guide more effective irrigation, helping growers save water and improve fruit quality. Though a relative newcomer to Washington state, the Israel-based company has been supporting California grape, fruit and nut growers for several years.

Many of those crops have a history of precision irrigation, with crop-specific models developed by university researchers to help growers adapt and take advantage of new innovations in water stress sensing, including smart dendrometers, microtensiometers, sap flow meters and soil moisture sensors.

Apple growers have no such pre-existing framework, and while Washington State University physiologist Lee Kalcsits plans to start studying the potential of sensor-informed irrigation this season, for now, growers have to run their own experiments to see if the technology benefits their management.

Phytech believes its approach can fill that gap, said Oren Kind, the company’s chief commercial officer. Its model helps growers decide how to irrigate using the information the sensors provide by learning from each block over time.

“We believe at the end of the day, to do the right thing for the trees, we need to ask them how they feel,” Kind said.

With no apple cultivar-specific standard to follow, Kind recommends growers use the sensors to see how their blocks respond to irrigation, rather than make immediate changes. Problem blocks will make themselves apparent, he said, and growers can then adapt irrigation practices and see how the trees respond in a matter of days or weeks.

“It’s like raising kids: There’s no one way to educate kids, because every kid is different,” Kind said. “You have to find the right way to maximize the potential of each kid, and this is the approach we use for the trees.”

In general, he thinks Washington apple growers overirrigate, flushing nutrients and driving more vigor in the trees than needed. Armed with information from the sensors, and Phytech support that’s part of the company’s service model pricing, growers can feel confident adjusting irrigation approaches to meet their goals, Kind said.

Sundquist said in some blocks where he struggled to get fruit size or tree growth, he’s changed irrigation practices significantly, and in others, he hasn’t changed much at all. “I can tell you we’ve been running drip a lot more,” he said. One Granny Smith block that is usually one of the most stressed blocks on the farm looks better than it has in years, he said.

He’s excited about this data-driven approach to irrigation but cautions others considering it. “It’s a pretty steep learning curve,” Sundquist said. “You don’t just plug it in, and it works miraculously. You have to get immersed in it to see the benefits.”

Dendrometers have been around a long time, as a research tool, said Kalcsits, the WSU physiologist. But it’s relatively new for the tool to be repackaged in a grower-friendly platform, he said during a webinar WSU hosted to address grower questions about dendrometer technology.

“One of the big advantages is that it’s a plant-based indicator of water stress; they integrate soil moisture, rootstock uptake, scion conductance and the environmental conditions these trees are living in,” he said. But there’s not a lot of data available about what precision irrigation targets for apple cultivars should be to inform the use of the sensor, he said.

Kalcsits said in a follow-up interview that he will start a research project this season, as part of the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission’s Smart Orchard project, to look at using dendrometers and FloraPulse microtensiometers, another water stress sensor, developed by Cornell scientists, to optimize apple irrigation.

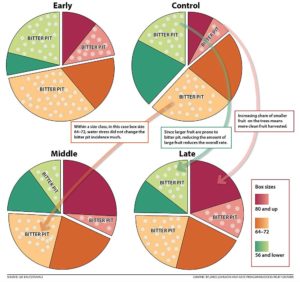

He thinks such tools could offer a real benefit to Honeycrisp growers, as his research has shown that overirrigating Honeycrisp leads to larger, more bitter pit-prone fruit.

The appeal of bringing more precision to deficit irrigation management for Honeycrisp led Washington Fruit and Produce Co. to test out Phytech’s technology last season, said Gilbert Plath, who assesses technology for the Yakima-based company.

“We are trying to stress these trees out, and you can go too far. What Phytech is trying to show is that measurement of: ‘Here, you are crossing that line now,’” Plath said. “We are looking at this mainly as a bitter pit mitigator, to make sure we can reduce that cullage at the end of the year and not hurt the trees.”

He likes the fruit growth sensors, because the goal of the deficit irrigation approach is to hit a target Honeycrisp size. “It has an easy-to-read graph that has a target line we should be on,” he said. “We see the reaction, how much it grows or doesn’t grow when you water.”

The report card, in terms of impact on packout, wasn’t available yet, Plath said, but he was optimistic that the technology helped the company be more precise with their water. Overall, he said the app is intuitive and easy to use. Another benefit is that it helps managers keep an eye on irrigators across different ranches, Plath said.

Sundquist said the data helps him work collaboratively with his irrigators to solve problems, too.

“It takes what could be an adversarial issue, if something isn’t working out, but (having the data) makes it collaborative,” he said. Having the water pressure sensors that track irrigation applications has helped his irrigators detect clogged filters and flow restrictions.

“It’s worth saying: Just because you deploy a technology doesn’t mean you don’t have to go outside,” Sundquist said. “You still have to have people ground-truthing it; you still have to dig a hole and feel your soil and make that correlation.” •

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment