In the United States, agricultural field workers experience an average of 21 days each year when the daily heat index — a combination of air temperature and humidity — exceeds workplace safety standards, and that number is projected to nearly double by 2050 and triple by 2100, according to a new study published in Environmental Research Lettersin April.

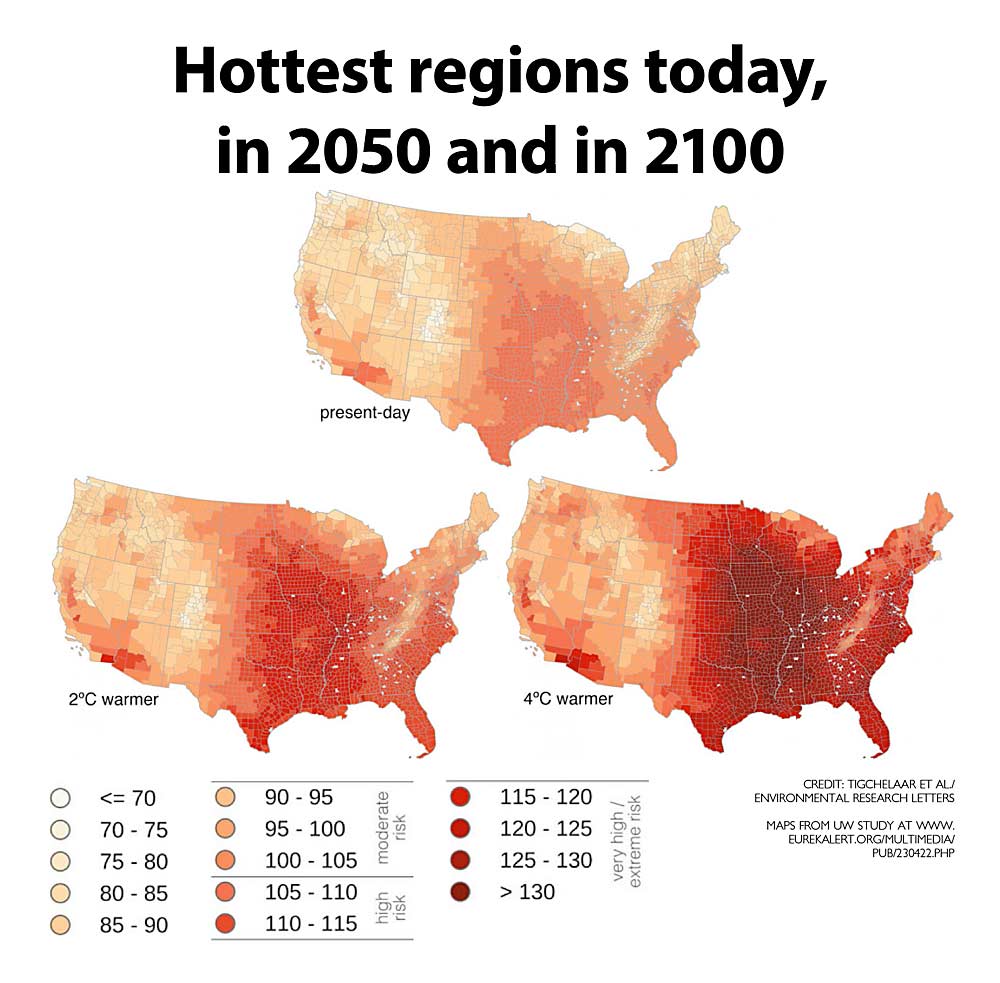

The study compares the current average daily heat index in crop-growing U.S. counties at three points in time: at present; in 2050, with an expected warming of 2 degrees Celsius; and in 2100, with an anticipated warming of 4 degrees Celsius if climate change continues without mitigation. It also presents strategies the agricultural industry could implement to help protect the health of its workers, according to lead author Michelle Tigchelaar, who conducted most of the research for this study while she was a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Washington. She is now a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford University.

Prior to this study, Tigchelaar’s research centered on climate change and its impacts on insect pests and crop yields, but the publicity about the death of a blueberry picker on a hot summer day in Washington in 2017 got her thinking about how increasingly hot summers affected the men and women toiling in the field. She reached out to June Spector, an associate professor in the UW Department of Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences, to dig a little deeper.

“Starting that work, I learned that already in our present-day climate, agricultural workers are at much higher risk from heat extremes than regular workers,” she said, noting that U.S. crop workers are 20 times more likely to die from illnesses related to heat stress than other civilian workers overall. “That’s what set us off on this study.”

Getting warmer

The researchers based the 2-degree warming in 2050 and the 4-degree warming in 2100 on estimates from the collaborative Climate Model Intercomparison Project, which combines the work of dozens of climate research groups.

“Unless really rapid decarbonization would happen, 2 degrees (for 2050) is kind of baked in. The 2100 estimate has a lot more room for our actions to impact whether we go beyond the 2 degrees or not, so 4 degrees (represents) what will happen if we don’t reform our energy economy,” Tigchelaar said.

To determine the effect on agricultural workers, they then focused on how climate change would affect daily heat and humidity in growing regions during the May-to-September season. The heat index is a measure used by both the National Weather Service and the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration for estimating potential health risks associated with environmental conditions, and the study’s description of unsafe workplace safety standards is based on National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health guidelines.

Currently, agricultural workers experience an average of 21 days per growing season when the daily heat index exceeds workplace safety standards, with an anticipated rise to 39 days by 2050 and 62 unsafe days by 2100, Tigchelaar said.

“Those are national averages, so they will be much higher in the Southeast than, say, in Washington,” she said, but the trend toward more unsafe days will play out across the country. For the western Michigan growing region, for instance, which currently experiences fewer than 10 days that are unsafe, Tigchelaar said the number would jump “to 10 to 20 by midcentury, and upwards of 50 in late century.”

In addition, heat waves — three or more days of at least 90 degrees Fahrenheit — will become more common. Currently, most counties with at least 500 agricultural workers experience a three-day heat wave about once a summer, but that will increase on average to five times per season by 2050, and between six and eight per season by the end of the century. Such prolonged heat may make it difficult for workers to find relief from the heat, even overnight if housing doesn’t have proper ventilation or air conditioning, she said, “and your ability to cool off at night is important for mitigating health impacts.”

Beating the heat

For growers and their workers, the question isn’t whether the summer will get warmer in the future, but what to do about it now. Tigchelaar listed strategies in the UW/Stanford study, including: switching to clothing suited for the heat, drinking lots of water, taking breaks when needed and easing work demands on especially hot days.

Clothing does make a difference, agreed Melanie Forti, director of Health & Safety Programs for the Association of Farmworker Opportunity Programs, a national advocacy group. “We highly recommend that farmworkers wear light-colored, loose-fitting and breathable clothing, such as cotton, and avoid any non-breathing synthetic clothing,” she said, adding that long-sleeved shirts are good options because they help protect workers’ skin from direct sun exposure.

Likewise, staying hydrated can greatly decrease the risk of heat illnesses, so farm managers should not only make fresh water available to workers but also readily accessible, perhaps through a portable water source that travels with the workers as they move through the orchard or field, Forti said.

In addition, Tigchelaar suggested a work structure other than the paid-by-the-piece model, because during piece-rate work, “even if there’s water available, workers are not incentivized to go and drink water,” she said.

Forti offered additional strategies: instituting a buddy system to help ensure someone notices that a co-worker is becoming overheated and gets that person to rest and drink some water; scheduling certain activities in the morning, such as maintenance or operation of heat-producing equipment; shifting the overall work schedule if possible to avoid the extreme heat of the day; and phasing in new workers so they can gradually become accustomed to the workload and to the summer weather.

These are the types of heat-beating strategies that the agricultural community everywhere should be considering now, and also thinking about for the future, Tigchelaar said.

“There has been little focus in climate change work on the people who are doing a lot of the actual physical labor in our food system,” she said. “As we think about a warming climate and who is most at risk and who will be impacted, farmworkers will be at the front of that line. And as we are seeing with this pandemic right now, when the most vulnerable are impacted, all of us are impacted.” •

—by Leslie Mertz

Related:

—Asking about masking

—Healthy strategies for smokey skies

Leave A Comment