A Washington State University plant ecologist is trying to take his water-saving subsurface wine grape irrigation system to the market.

While still collecting research data, Pete Jacoby has begun to commercialize his method with a $50,000 university entrepreneurial grant, a fabrication facility in Colfax, Washington, and a few interested buyers in California and Texas, where water demand is higher than in Washington, he said.

Interest in his approach is high “where water is really expensive or rare,” he said.

His subsurface system simply diverts water from a vineyard’s drip system to a line that connects through PVC pipes into the root zone of each vine. This direct-to-the-roots approach allows vines to produce a full crop on 60 percent of normal water with no apparent penalty in subsequent years, according to his research findings.

Jacoby developed the approach, but he is forging ahead without a patent, which WSU’s Office of Commercialization declined to pursue. That’s common, said Albert Tsui, a patent attorney and business development specialist at WSU. Sometimes inventions use so many off-the-shelf parts that enforcing a patent would be impossible, or at least more trouble than it’s worth.

Jacoby admits growers could go buy the parts and make it themselves but probably wouldn’t want to, at least not judging from the interested calls he gets from potential customers in Napa, California, and an area of Texas near Lubbock. “The first question when I get a call from a grower is: ‘Where is this thing available?’” he said.

The Auction of Washington Wines provided seed money through the state grape and wine research program for Jacoby’s work in 2016, funding three years of work as a proof-of-concept investment, said Melissa Hansen, research director for the Washington State Wine Commission. He used that money to attract state, federal and private grants that collectively topped $600,000.

“The proof of concept works, it’s just not really been tried on a really large scale,” she said.

She sees the potential in Paso Robles, California, — for example — where wine grapes are expanding into dryland hills and relying on irrigation from groundwater, a limited resource soon to be regulated by a whole slew of new state mandates. It might help in Washington, too, if there is significant drought.

Jacoby has not finished his research, either. Through a project at a cooperating vineyard near Zillah, Washington, he is testing the effects of subsurface irrigation on replanted vines. In theory, delivering water below the surface will give those young plants a chance to catch up to their older neighbors, which need less water. The direct watering might also give the young vines a leg up on weeds.

That would come in handy for vines replanted in place of those rogued due to virus. In fact, the trial block was rogued this year for red blotch, and Naidu Rayapati, a virologist at WSU-Prosser, is collaborating on the research. Their first of three years has been funded by $25,000 from the wine commission.

Previous underground attempts

Subsurface drip irrigation technology has been part of irrigated agriculture since the 1960s and is used in vegetables, berries, potatoes and more. Melons, strawberries, tomatoes and onions have shown improvement in yield and quality, according to the Colorado State University Extension website. Startup costs run between $1,200 and $1,500 per acre, according to the U.S. Natural Resources Conservation Service technical handbook, which also lists tips by crop. Jacoby has not yet determined costs for his method.

Jacoby himself found an obscure research paper from Libya, published in the 1980s, where scientists tried irrigating table grapes by pouring water into a tube poked into the ground near the roots. They reported the same quality and quantity of fruit as the surface watering.

“I wasn’t the first one to think of this,” Jacoby said.

Typically, subsurface methods involve a buried line, which dirt sometimes clogs and gophers sometimes chew. Whatever the cause, farmers won’t know they have a problem until vines start dying, Jacoby said.

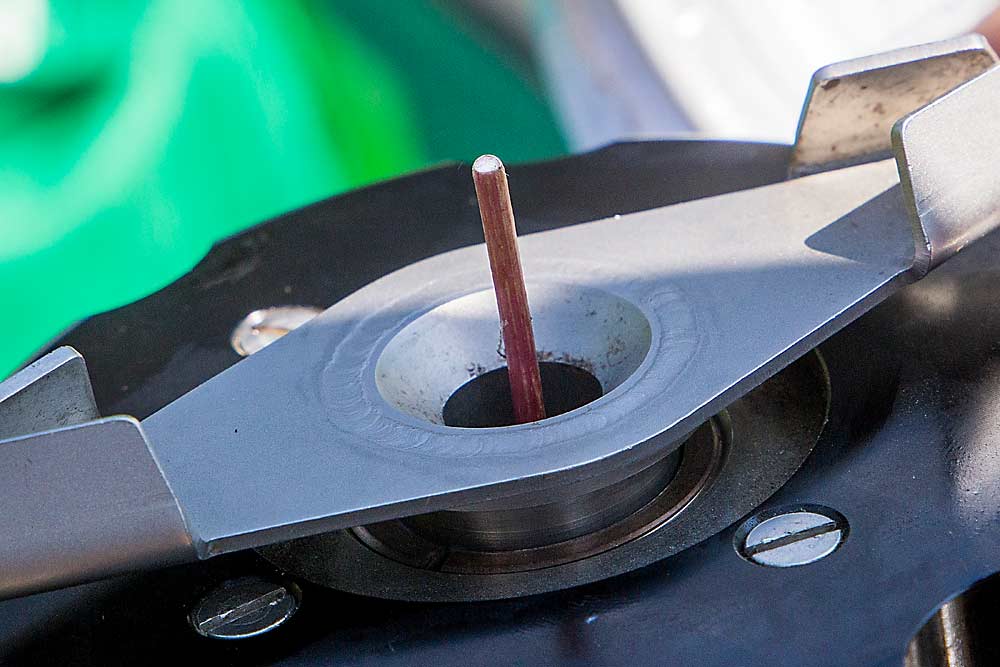

With Jacoby’s method, most of the infrastructure is above ground. The lateral line hangs roughly 12 inches above ground. Individual outlets divert to emitters that rest inside the PVC pipe protruding roughly 6 inches above ground. The emitters are accessible without any digging and topped with a red plastic cap, designed to pop off if pressure backs up inside the PVC pipe, which would indicate a clog below the surface. That’s never happened in three years of trials, Jacoby said.

The PVC pipe, driven into predrilled holes, reaches 1, 2 or 3 feet deep, in his trials. His results show no difference between the depths, so he’s most likely going to sell his system with 2-foot pipes. Wine grapes typically don’t send roots much deeper than that, he said.

He also plans to recommend setting the system at about 60 percent of normal water. That’s where he’s noticed the best results. His trials at 40 percent showed reduced yields.

Jacoby suspects underground watering might work for tree fruit or nut orchards, which typically require more water than do wine grapes. He set up a small-scale trial with a hazelnut farmer east of Portland, Oregon.

Kiona Vineyards in Benton City, Washington, hosted Jacoby’s original trials. Owner Scott Williams likes the idea. He, too, has received inquiries from growers in California and Texas.

“The technology has its place, particularly as it gets hotter and drier and water gets scarcer,” said Williams, who often grants WSU researchers access to his vineyard for irrigation projects.

His concern is with mechanization. Jacoby’s lines hang well below the fruiting zone that a harvester would hit, but vineyard managers are using machines for more and more chores. Extra wires and tubes sometimes get in the way, in Williams’ experience.

But he vouches for Jacoby’s approach. The vines in his experimental block seem just as happy and the grapes just as good as the ones outside.

“It’s proven that you can grow pretty darn good grapes on a less percentage of water pretty consistently,” he said. •

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment