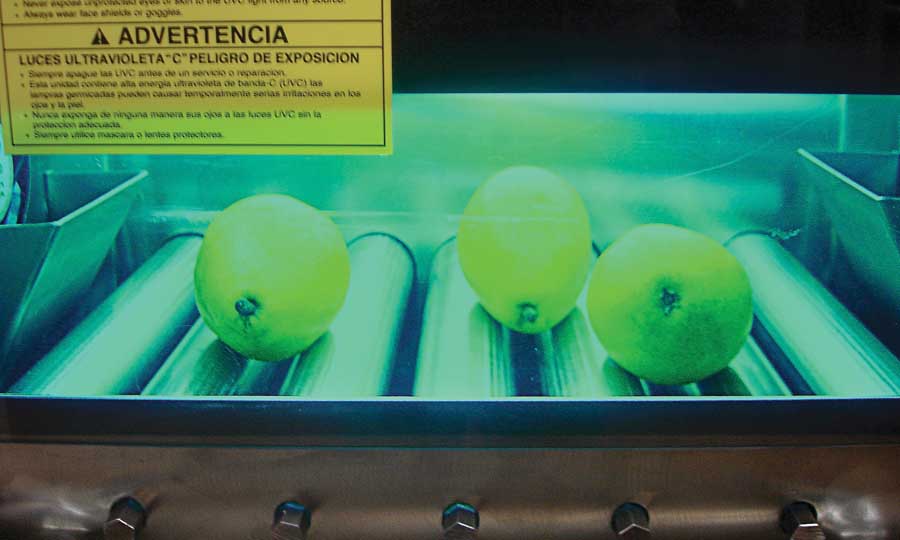

Pathogens on the surface of organic pears were significantly reduced after exposure to UV-C light. (Courtesy Roopesh Syamaladevi/Washington State University)

Ultraviolet C light can control pathogens on fruit surfaces and could potentially be used on fruit packing lines to ensure food safety, says a team of Washington State University scientists.

The team, led by Dr. Shyam Sablani, biological systems engineer, did laboratory studies to assess how well UV-C light could control Escherichia coli 0157:H7 (E. coli) and Listeria monocytogenes (listeria) on fresh apples, pears, cantaloupes, strawberries, and raspberries.

UV-C light has a shorter wavelength than UV-A or UV-B light. It is present in sunlight, but is completely absorbed by the ozone layer and the Earth’s atmosphere. Lamps that emit UV-C light are commercially available.

UV-C light cannot penetrate solid objects but can sanitize surfaces. It works on microorganisms by destroying the nucleic acid and disrupting the DNA. It has been used to sanitize food contact surfaces as well as drinking water and contaminated air.

Previous research has shown that UV-C light can be more effective against E. coli than chlorine, ozone, or electrolyzed water. UV-C light, at a level of 254 nanometers, is approved for microbial reduction in food and juice.

Although some juice processing plants in the United States use UV pasteurization, UV-C light has not yet been used in fresh fruit packing houses because there was no research to show how effective it could be. Packers typically use liquid sanitizers such as sodium hypochlorite, chlorine dioxide, and peroxyacetic acid, to disinfect fresh produce. The fruit are also sometimes brushed to reduce the microbial load.

“Now, we’re realizing this is not foolproof and there’s a possibility these existing treatments are not enough to ensure the safety of the product all the time,” Sablani said. “We’ve been thinking UV-C light could be another intervention.”

The researchers believe that a UV-C treatment could be used to satisfy the Food and Drug Administration’s requirements under the Food Safety Modernization Act. It could also be used by organic fruit packers who can’t use chemical sanitizers.

Interest in the technology is high, Sablani said, because it’s simple to implement and inexpensive.

Inoculated

For the WSU study, researchers used fresh organic Fuji apples, d’Anjou pears, cantaloupes, and raspberries. Small slices from the fruit were inoculated with E. coli and L. monocytogenes and then treated inside a table-top UV-C light emitter.

Sablani and his colleagues found that the light treatment could reduce pathogens by up to 99.9 percent on apples and pears. L. monocytogenes was more resistant to the UV-C treatment than E. coli. Fruit were inoculated with high levels of the pathogens in order to put the treatment to the test. In a real-life setting where good agricultural practices are used, pathogen populations on fruit would be significantly lower and the treatment would likely be more effective on both pathogens, he said.

The treatment was more effective on smooth-skinned fruit than those with rougher surfaces, dimples, seeds, or druplets and was more effective on apples than on pears.

“If you have smoother-skinned fruit, then this technology is really great,” Sablani said. “If the fruit are rough but the contamination level is low, it also works quite well.”

Tunnel

UV-C is harmful to the naked eye, but UV-C lamps could be enclosed behind protective barriers inside a tunnel on a packing line, with fruit exposed to the light as it passes on a conveyor belt.

In the experiments, most, but not all, of the microbes were killed in the first minute of treatment. Sablani said the dose could be increased by using more lamps to ensure that the treatment would be effective at the speed at which fruit typically move along the packing line. There would be no need to slow down the line or make major modifications.

UV-C treatment has no or minimal effect on the sensory quality of fruit, Sablani reports. After the experiments, sensory panels consisting of 30 to 40 people were unable to detect a difference between treated and untreated pears. However, after the pears had been held for four weeks they could perceive differences in sensory parameters.

But after fruit had been stored for an additional four weeks, fewer panelists could perceive differences in overall quality between treated and untreated fruit. Sablani said green is affected more by UV-C light than orange or red. The treatment does not affect shelf life, as it affects only the surface of the fruit.

Also taking part in the experiment were: biosystems engineer Dr. Roopesh Syamaladevi, Extension food safety specialist Dr. Karen Killinger, and food safety specialist Dr. Achyut Adhikari, who is now at Louisiana State University.

The study was partially funded by a grant from the Biological and Organic Agriculture program of WSU’s Center for Sustaining Agriculture and Natural Resources. •

– by Geraldine Warner

Leave A Comment