Fotonovelas. On-air experts. Workplace visits bearing flyers.

Radio KDNA of Granger, Washington, a Spanish-language public radio station, has launched an educational campaign with the Washington Growers League to convince workers to take the COVID-19 vaccine when it’s their turn in the distribution rollout, both for their own good and the good of their communities.

“La vacuna es importante,” said Elizabeth Torres and Francisco Rios, more than once, during their weekly broadcast Aqui y Alla. “The vaccine is important.”

Torres, the project manager, said the outreach is aimed at “giving the farmworkers the support and the hope that we are all part of the community and we can end this pandemic.”

With grants received from the Washington State Department of Health, KDNA and the Growers League have a broad plan to increase Northwest farmworker vaccine awareness, as well as promote social distancing, masks, hygiene and all the behavior adjustments recommended to prevent the spread of the virus in the first place. The Pacific Northwest Agricultural Safety and Health Center at the University of Washington and the state Department of Labor and Industries also partnered on the plan.

KDNA’s work marks one example of efforts across the country to spread the message about the importance of the coronavirus vaccine among farmworkers, most of whom speak a language other than English, don’t have medical insurance and lack access to needed information, advocates say.

Late last year, a California farmworker group, TODEC, visited laborers to debunk vaccine myths during their breaks from picking vegetables — such as the conspiracy theory that vaccines contain microchips for government monitoring. Health providers share accurate information during on-site COVID-19 testing.

California farmworkers began receiving COVID-19 vaccines in late January, though the rollout started slowly, like everywhere else.

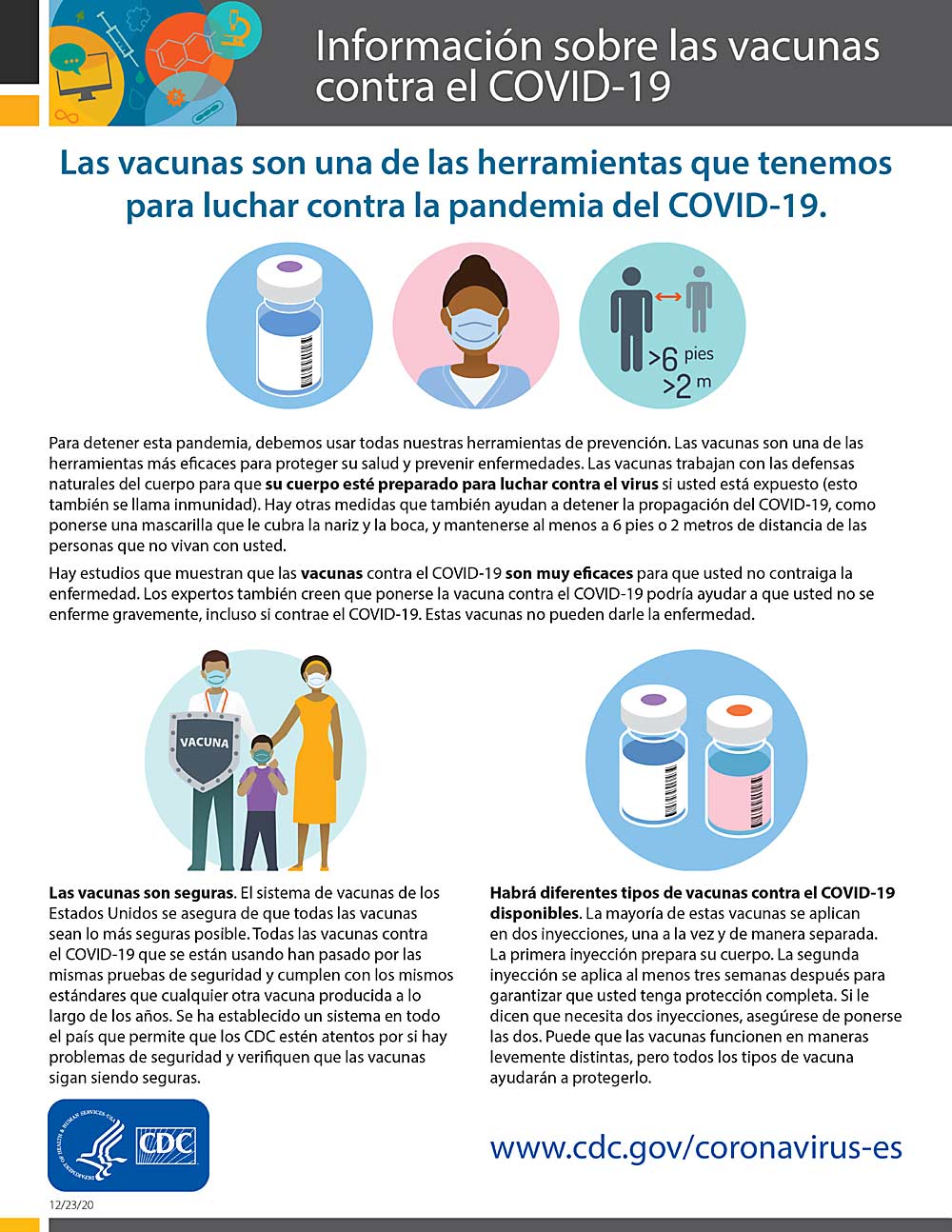

Myths and valid concerns alike circulate in all groups, not just with Spanish-speaking farmworkers. And it’s not just agriculture looking to encourage workplace vaccination. The Wall Street Journal recently published stories of companies holding vaccination “parties” with cake and socially distant games. The federal Centers for Disease Control, CDC, released a toolkit in several languages that all employers can use to communicate with their workers about the vaccine. (See “Online resources” on Page 47.)

Late last year, when CDC staff visited farmworkers in Douglas County, Washington, they were surprised by some vaccine hesitancy, said Jon DeVaney, president of the Washington State Tree Fruit Association. Agricultural employers for months had been lobbying to secure a high vaccine priority for farmworkers, assuming it would be welcomed as an objective positive.

“Some may view getting our workforce priority for the vaccine as treating them like guinea pigs,” DeVaney said in December at the group’s annual meeting. “I’ve heard that phrase be used. So, we have to be ready to respond.”

In January, WSTFA was one of several groups to ask Washington Gov. Jay Inslee to bump up farmworker vaccination timeslots and put together an education campaign with the industry.

Worker questions

The UFW Foundation, the charitable arm of the California-based United Farm Workers advocacy group, is reaching out to workers, as well. In January, the foundation broadcast a webinar interview in Spanish with Dr. Jose Romero, Arkansas secretary of health and chair of the CDC’s advisory committee on immunization practices.

More than a dozen farmworkers from Michigan, Washington and California asked questions, such as: If the vaccines are 95 percent effective, what will happen to the unlucky 5 percent; and is getting the vaccine voluntary or required?

In the Northwest, workers told the UFW Foundation they are concerned about possible reactions to the vaccine, missing work and if they will be charged, said Zaira Sanchez, Northwest emergency relief coordinator. Another common question touched on the religious: Were aborted fetuses ever used in the development of the vaccines? (In December, the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops called the vaccine “morally justified” because the public benefit of it outweighed any potential link to abortions that most likely occurred decades ago, if at all.)

The UFW Foundation is publishing a facts vs. myths flyer and Sanchez’s team plans to hand it out at Washington and Oregon farms. It’s not about trying to tell people what to do, Sanchez said, just informing them. “We want them to have confidence in their decision,” she said.

The foundation set up a Good Fruit Grower interview with a 49-year-old farmworker who lives and works in orchards, vineyards and hop fields near Prosser, Washington. The husband and father of five asked to remain anonymous.

His mind is made up to receive the vaccine when his number is called, he said. However, he hears little discussion of the vaccine among his co-workers. It’s like it’s not even real to them, he said. “A lot of co-workers don’t talk about the vaccine because it’s not even feasible for them to go and get it.”

Farmworker communities get their information by word of mouth; if the industry wants to deliver a vaccine message, they need to do it on-site and in the fields, he said. He also thinks growers should host vaccinations at the workplace and let workers stay on the clock.

“They won’t leave work to go get it,” he said. “They don’t want to lose the hours.”

Voluntary is best

Growers may mandate the vaccine. Workplace privacy rules prohibit supervisors from asking their workers about medical information, but vaccination does not fall under that category, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission announced in December on its website.

Vince Seaman, an epidemiologist, recommended the “carrot” over the “stick” approach when he spoke at a virtual H-2A employers meeting organized by wafla in January. He suggested telling workers they might get to move around more freely and live with less restrictive rules if they get the vaccine.

“We don’t want to force people to do something they don’t want to do,” said Seaman, the senior program officer for polio at the Global Development Division of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. He has participated in vaccination programs all over the world.

Growers should keep meticulous records about their employee health information as allowed, in this case vaccinations, something they have been doing well so far during the pandemic, he said. He does not believe there are any vaccine requirements for H-2A workers leaving Mexico for the states.

In Central Washington, many farmworkers have not made up their minds.

“A portion of our community is unsure if they’re going to get it or not,” said Torres, the outreach manager for Proyecto Bienstar, or Project Wellness, an ongoing campaign of Radio KDNA.

The 41-year-old station has a long history of health-related publicity efforts, ranging from drug abuse to nitrates in well water to kids brushing their teeth. They record public service announcements to read on-air, interview doctors on Aqui y Alla and publish fotonovelas, a form of visual printed storytelling.

“It will be like a soap opera, but on paper,” Torres said.

For the coronavirus outreach, they plan to feature photos of farmworkers talking through quote bubbles about handwashing, commuting and ride-sharing during the pandemic and, of course, vaccines.

Porque, la vacuna es importante. •

—by Ross Courtney

Online resources

Online resources for agricultural employers to help spread the message about vaccinations:

—Radio KDNA of Granger, Washington, a Spanish-language public radio station, plans to host interviews with doctors and other experts regarding the coronavirus on Aqui y Alla, which airs at 4 p.m. every Friday. In the Yakima area, listen at 91.9 FM or online at kdna.org/ways-to-listen.

—The U.S. Centers for Disease Control has published toolkits with posters (see example at right) available for download at cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/toolkits/essential-workers.html.

—The UFW Foundation suggests viewing its Facebook page to find videos and other coronavirus-related updates. Go to: facebook.com/UFWFoundation.

Leave A Comment