The historic 1976-1977 drought that hit western states made a lasting mark on a Washington State teenager and began what became a lifelong quest.

For more than 30 years, Urban Eberhart has worked to improve water supplies for the Yakima River Basin. With the start of construction of a project on Manastash Creek, he’s finally seeing the fruition of the first of what’s hoped to be many water projects that are part of an integrated plan for the Yakima River Basin.

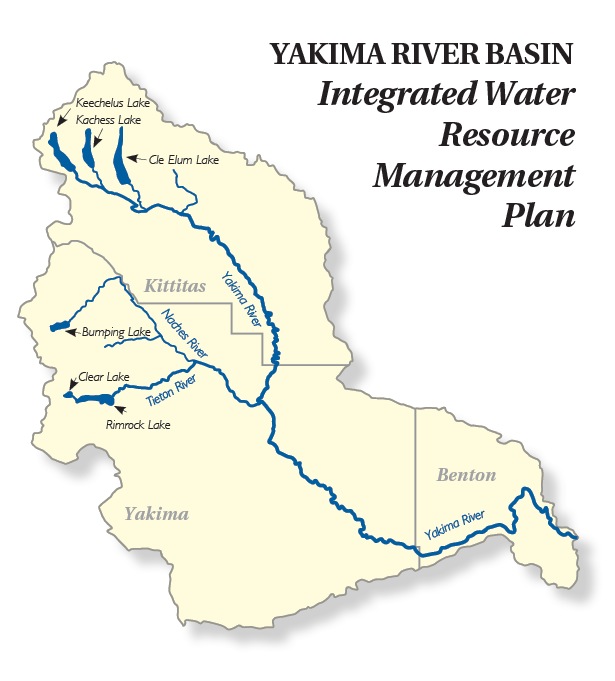

The Manastash Creek is a tributary of the Yakima River in central Washington’s Kittitas Valley that provides water to about 4,500 acres of farmland. It once served as important habitat for steelhead and coho salmon.

Last year, with cost sharing between creek users, the Washington State Department of Ecology, Kittitas Reclamation District, and the county conservation district, the project broke ground. Three miles of an unlined lateral are being converted to a pressured pipeline, conserving an estimated 1,300 acre-feet of water annually and increasing access to 25 miles of habitat for steelhead, trout, and salmon.

Eberhart, in his early 50s, lives, breathes, and dreams water. If you were a stranger and just met the Ellensburg, Washington, tree fruit and hay grower, you’d leave knowing about the need for additional water storage in the Yakima River Basin and how an integrated plan will increase water supplies for fish and wildlife, farmers, and municipalities.

He’s a cheerleader for the Yakima River Basin Integrated Water Resources Management Plan (called the Integrated Plan) and shares his message with anyone willing to listen.

One of Eberhart’s neighbors once told him, “I’d like to stop and say hello, but I don’t have 20 minutes to talk water.”

Improving the water supply for the drought-prone Yakima River Basin is more than his hobby.

In the past four years, Eberhart traveled thousands of miles to participate in hundreds of meetings and testify in countless state and federal legislative hearings and news conferences. Sometimes he dreams of debates with opponents.

“He has a tremendous amount of energy,” said Dan Silver, a consultant from Olympia who is coordinating the workgroup behind the Integrated Plan. “Urban has a strong sense of civic responsibility and epitomizes how the various interests of the group are committed to something bigger than themselves. You can always count on him to testify at a moment’s notice or attend

a meeting.”

Jim Trull, manager of the Sunnyside Valley Irrigation District and a member of the project’s working group, said, given the importance and immensity of the project, a champion was needed to promote it. Eberhart was hired by the Yakima Basin Joint Board to represent those common interests. The board is a consortium of the Yakima Basin’s five major irrigation districts and the City of Yakima, formed to address issues dealing with irrigation, fisheries, the Endangered Species Act, and other challenges.

“Urban is perfect for the job because he is articulate, energetic, and knowledgeable about the basin’s interests,” Trull said. “While Urban’s farm is in an irrigation district with proratable water rights, he has put that personal bias aside to include protection of more senior rights and supporting funding for conservation, storage, fish passage facilities and habitat restoration.”

During the 1970s, Eberhart watched periodic droughts overwhelm growers in the irrigation district that supplied his family’s farm. A 1977 drought was especially hard on his family’s farm in the Kittitas Valley, where his father also worked as a geography professor at Central Washington University in Ellensburg. The family grew apples, pears, and hay irrigated with water from melting snowpack stored in dams and reservoirs.

Eberhart vividly recalls the drought announcement made in mid-February of 1977, his junior year in high school. Farmers with proratable irrigation water (junior water rights) were to receive 6 percent allocation for the season.

“Farmers tied to the Yakima River Basin for irrigation hadn’t experienced such a cutback before,” he said, explaining that in previous droughts all users had received reduction, not just proratable users.

This was the first serious drought since the Yakima Irrigation Project was completed. Until that time, most people had assumed the watershed would always meet the basin’s water needs. “Six percent was quite a shock.”

He remembers difficult decisions by his father to keep trees alive. “I learned early in life that nothing works in agriculture without water,” he said.

Though the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, responsible for water management of the Yakima River Basin, eventually increased the allocation that year to 70 percent, it came too late in the season for most farmers, who had already removed fruit off trees to keep them alive or had left fields fallow.

Awfully young

The young Eberhart began following the political and legal processes of the Yakima River Basin and the need for additional water storage. He watched his father testify at meetings that led to the Yakima River Basin Water Enhancement Project, passed by Congress in 1979, that authorized a storage feasibility study, among other things.

With a keen interest in water, Eberhart was elected to the board of directors of the Kittitas Reclamation District in 1986.

“At 26, I was awfully young for an irrigation district board,” he said. “At the time, I was one of the youngest members of irrigation boards in the state.”

Eberhart will complete 28 years of board service this year. Since that first year on the Kittitas Reclamation board, an irrigation district created in 1911 to serve 60,000 acres, he’s dealt with five significant droughts resulting in reduced water allocations from 37 to 67 percent. There have been times when he’s trucked in water to keep his trees alive.

Washington’s prior appropriation doctrine follows a “first in time, first in line” concept. The Kittitas Reclamation District, along with the Yakima, Tieton, Roza, and Kennewick irrigation districts in the Yakima Valley, were established in 1905 or later and have junior water rights because they were organized and constructed as part of the Federal Irrigation Project.

Entities holding rights predating the May 10, 1905, withdrawal date by the Bureau of Reclamation have senior rights. According to a federal consent decree issued in 1945, during a short water year, entities with senior right water entitlement are fulfilled first, and what’s left is prorated to junior right users.

Not enough

Before the early 1970s, the Columbia River Basin, including the Yakima River, was in a wet cycle and enjoyed abundant snowpack. But the climate began changing in the 1970s and droughts have become more frequent, with increasing severity, said Eberhart.

“Some call it global warming, I call it climate change, but something has definitely changed.”

A report on the impact of long-term climate change by the state Department of Ecology shows that by 2040 the Yakima River Basin will have some of the most severe impacts of low summer flows in

the state.

The Yakima River Basin supplies water for agriculture, municipalities, fish, natural resources, and recreation. Five reservoirs with storage capacity of 1 million acre-feet of water capture an average annual runoff of 3.3 million acre-feet. Annual irrigation deliveries are 1.7 million acre-feet. Snowpack is the “sixth reservoir,” but the region is in dire trouble without it.

“Surface water is over appropriated, and our snowpack is declining,” Eberhart said. The basin supplies water to 500,000 irrigated acres—acreage that includes perennial, high-value crops like apples, cherries, hops, and grapes. “Of the total water supplied by the Yakima River Basin, about half of the water users are proratable and lose water in a drought year. That has really magnified this issue.”

Farmers are not the only ones that suffer in a drought. Low summer flows also impact fish. The Yakima River and its tributaries were once home to huge salmon and steelhead runs averaging 800,000. Runs today average 15,000 to 20,000, reduced in part by reservoirs that were constructed in the early 1920s without fish ladders.

The solution to the water problem, Eberhart is convinced, is the Integrated Plan, a comprehensive plan developed by irrigators, the Yakama Indian Nation, environmentalists, natural resource and fishery representatives, and local, state, and federal agencies and governments (see “Integrated plan moves forward, page 34).

The ambitious 30-year plan improves water supply for proratable users to 70 percent during drought years, provides opportunities for ecological restoration and enhancement, including fish passages at existing reservoirs, and contributes to a sustainable economy and environment.

It’s been more than 30 years since the 1977 drought. Eberhart, still working on Yakima River Basin water issues, believes the Integrated Plan is the best chance for new and expanded storage reservoirs to become reality. Now, he just needs to live another 30 years to see the plan completed •

Leave A Comment