Can a seafood byproduct boost biopesticides to help growers control apple scab and reduce the use of fungicides?

That’s a question researchers from the University of New Hampshire and Penn State University seek to answer. They only have one year’s worth of data so far, but results look promising.

The researchers are investigating a natural compound called chitosan, which is derived from shrimp or crab shells that are ground into powder. They want to study how well it prevents apple scab before harvest, in combination with biopesticides, said Liza DeGenring, a UNH graduate student and one of the researchers. There is evidence that chitosan may act as a food source for biopesticides, stimulating production of antifungal enzymes and enhancing their usefulness, she said.

Scab is one of the most damaging pathogens facing New Hampshire apple growers, she said. Most of the state’s apples are sold via U-pick orchards and farm markets, where blemish-free fruit is a must.

DeGenring, whose research focuses on increasing the use of biopesticides, got the idea to study chitosan from her faculty advisor, Anissa Poleatewich, an assistant professor of plant pathology at the New Hampshire Agricultural Experiment Station. The new project is based on work Poleatewich did as a graduate student at Penn State.

“I observed some promising results with chitosan applied postharvest,” she said. “After completing my degree, I had some unanswered questions relating to synergisms between chitosan and biopesticides. Many years later, I decided to pick this work back up again.”

As principal investigator, Poleatewich is helping DeGenring plan the research project.

“We are still in the early stages, but we are seeing some evidence that chitosan can suppress foliar diseases,” Poleatewich said.

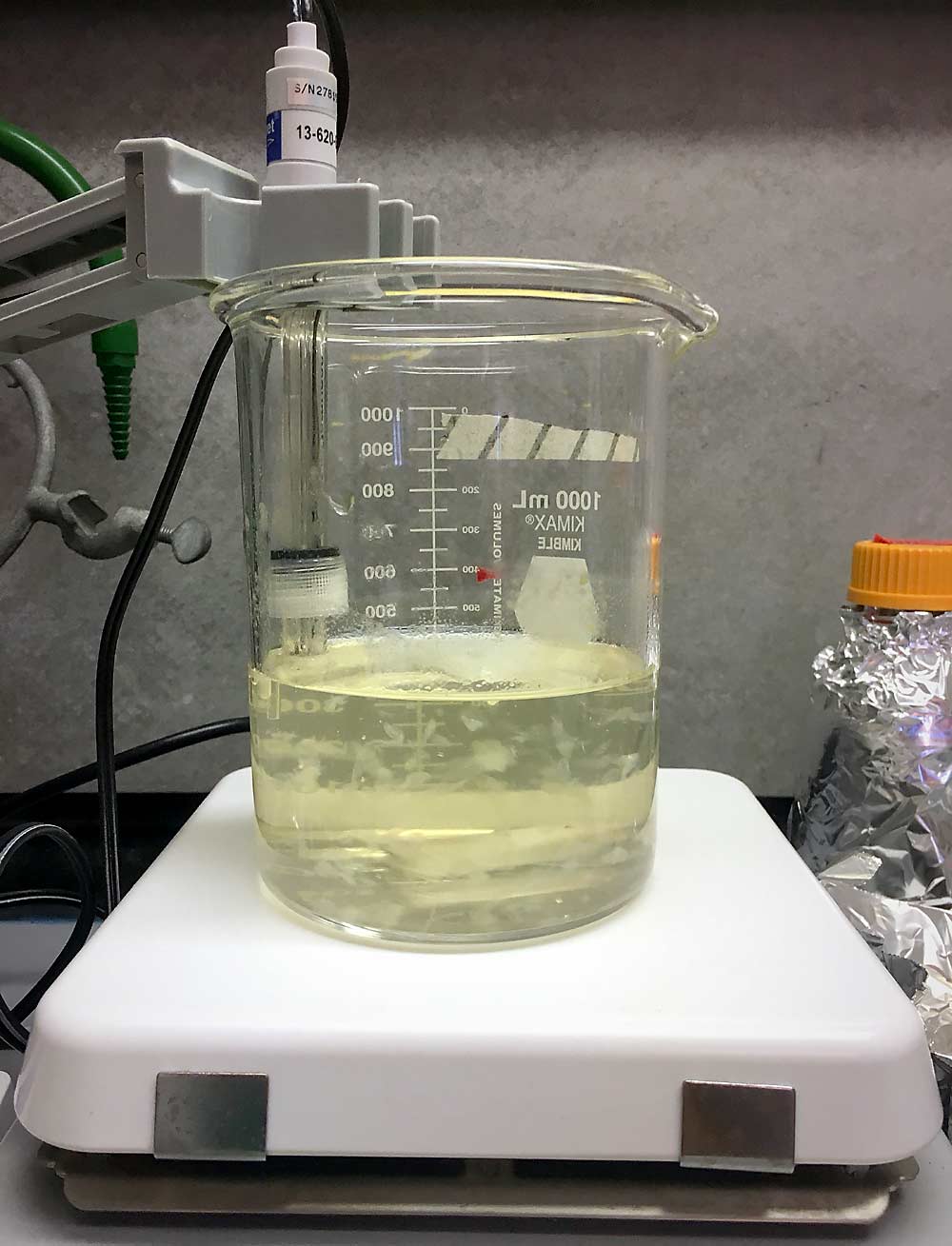

To apply chitosan in the form available commercially, researchers dissolve it into a liquid with other ingredients before applying it to plants.

To expand their research, the New Hampshire team connected with Kari Peter, a tree fruit pathologist at the Penn State Fruit Research and Extension Center in Biglerville, Pennsylvania. They needed access to an untreated control — trial trees that don’t have to be sprayed with fungicides — unlike the commercial orchards they work with in New Hampshire.

The pre-coronavirus plan was for DeGenring to lead the field work in Pennsylvania last year. The pandemic scotched that plan, however, forcing the research team to “get creative,” Peter said. Peter’s team ended up executing the Pennsylvania research, while she and DeGenring planned and shared results over Zoom.

In addition to the untreated control, Peter added chitosan to a conventional treatment (Manzate Pro-Stick and captan) and a “reduced risk” treatment (Microthiol Disperss and Regalia). Though it’s only been a year and results aren’t definitive, so far the use of chitosan has slightly reduced scab incidence overall, she said.

DeGenring hopes to continue the project with two full summers of field trials in both states. She’s also studying chitosan’s effects on fruit rots and other postharvest problems with Johanny Castro, one of Peter’s graduate students. •

—by Matt Milkovich

Chitosan, when fed to plants has the property of mimicking insects eating the plant, very similar to the effects of UV A and B in horticulture lighting and sunlight.

The plants response to chitosan or UV is to strengthen cell walls and release resins in greater amounts to protect the fruit bearing parts of the plant.

In the highest concentrated sunlit areas of the world where lux gets to 100,000, flowers exhibit this release of resins and flower production that’s 10 to 20 percent greater than the rest of the planet.

Agriculturally, we’ve been using chitosan on the farm since the 70’s in various forms.