The worst thing that could happen to Honeycrisp is that it becomes so popular it takes the same road that led ultimately to the falling away of the Red Delicious variety, says an early grower and packer of Honeycrisp.

Dennis Courtier, owner of Pepin Heights Orchards, Inc. in St. Cloud, Minnesota, fears Honeycrisp, with demand and high prices, could become overplanted, planted in the wrong places, harvested at the wrong time, stored wrong or for too long, and ultimately fail to consistently deliver the unique eating experience that Honeycrisp consumers found when they got their first bite of the fruit.

Customers are routinely willing to pay premium prices for Honeycrisp apples, but whether they will do the same for multiple other varieties is, for growers, a million-dollar question. O. Casey Corr/Good Fruit Grower)

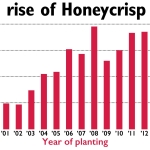

A survey conducted by Tree Top, Inc., shows that 22 percent of the trees planted by Washington nurseries in 2014 were Honeycrisp. And that doesn’t take into account trees propagated by growers themselves.

Would Honeycrisp have done better as a club variety, managed by people who can control such things?

That, of course, is what managed varieties are all about, Courtier says. But the first step is getting the right apple.

“You need to start with something worth building a brand around,” he said in an interview with Good Fruit Grower.

Courtier believes that a club apple, to be successful, has to be sufficiently different from other varieties. He is critical of breeding efforts that aim to get more Honeycrisp-like apples.

“That slot is filled,” he said.

After Honeycrisp began to be widely accepted, breeders began turning out Honeycrisp crosses, much the same as happened with Gala 15 years earlier.

Still, Courtier and the Next Big Thing Cooperative have pinned their hopes on SweeTango, which is a Honeycrisp cross. “If there’s an avalanche of new varieties, at least SweeTango has the good fortune of being at the front of it,” he said. “We began working with what was to become Minneiska/SweeTango in 2004.”

At one time, SweeTango was touted—by the breeders at the University of Minnesota themselves—as the replacement for grower-unfriendly Honeycrisp. Courtier believes SweeTango will hold its own in the race for a place on the shelf.

Not surprisingly, Courtier thinks SweeTango is a better apple—easier to grow, with fewer quality problems, and a higher acid level that moderates the Honeycrisp sweetness.

At the time the variety was patented by the University of Minnesota in 2008, it was promoted for “ its early ripening season, its crisp and juicy texture, and its unusually long storage life for an early ripening variety.” The university breeders considered it an improvement over Honeycrisp.

“It’s the best tasting apple there is,” Courtier says of SweeTango.

“Over the years I’ve done hundreds of blind side-by-side tastings of SweeTango and Honeycrisp. I’ve had exactly one person prefer Honeycrisp. SweeTango simply has a more complex flavor.”

He’s also pleased with how things have gone since Next Big Thing was formed to grow and market the apple. While the number of growers is limited (there are 47 members but 65 growers), they are spread out from Washington State to Nova Scotia in a somewhat uniform climate band, which compensates for weather differences that can reduce production in some areas in some years.

The idea was to market the apple within the four months of its storage life—and be satisfied with that. Courtier thinks the market can handle apples that are, like Starbucks’ pumpkin-spiced latte at Halloween, “limited time offerings.” •

Leave A Comment