Illustration: Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower)

Conventional wisdom for years held that wine grape varieties fell into two camps: isohydric and anisohydric. Isohydric plants hold on to water. Anisohydric plants, not so much.

That means some respond to water stress and some don’t.

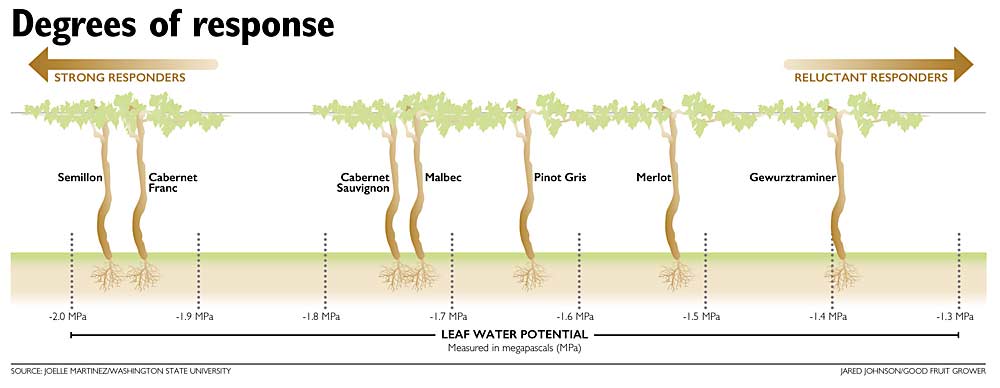

The truth is more nuanced, said Joelle Martinez, a Washington State University Ph.D. candidate. Different varieties fall across the spectrum for their ability to hold on to water, not into two clean categories, Martinez determined through her four-year Ph.D. project under the guidance of her mentor, Markus Keller, a viticulturist at WSU’s Irrigated Agriculture Research and Extension Center in Prosser.

“Just like people,” Martinez said. “You can’t put people into only two groups.”

Thus, growers must take a more precise approach to water stressing wine grapes, scheduling irrigation specific to their variety and how it retains and loses moisture.

Wine grape growers usually intentionally stress their vines with drought-like conditions to prompt the plants to produce fruit with certain quality traits sought by winemakers. Some have complained they stress and stress and stress, but their fruit quality doesn’t seem to respond. On the other hand, of course, vines have their limits. Stress them too much and productivity will decline, and eventually the plants will die.

The industry’s one-size-fits-all approach leaves too many varieties over- or under-irrigated, Keller said. Through her research, Martinez hopes to give growers tools that would allow them to more accurately find that sweet spot of mild stress. In fact, Keller recruited her for this project.

“This is why I came,” she said. “I was hired to do that.”

The research

From 2015–2018, Martinez studied how miserly 18 varieties of wine grape vines held on to the water they pulled from the soil.

To do that, she used pressure bombs, devices that measure leaf water potential, to quantify the water pressure inside a leaf and how the plants dropped that leaf water potential to compensate for increasingly severe drought conditions. Some varieties dropped their potential to -1.3 megapascals, some went even further to -2.0 megapascals.

A pascal is a unit of pressure. A megapascal is 1 million pascals.

For four years, Martinez rose in the wee hours of the morning — when the vines are shut down — to measure the leaf water potential at WSU’s Roza research vineyard north of Prosser and returned at noon, when transpiration was at its highest.

Not only do varieties hold water at different levels, she determined, they lose it at different rates over time. Thus, growers must monitor the leaf water potential over time to follow the pattern of how it drops.

At one extreme, varieties show a water potential that does not change until the vine reaches a certain threshold of soil moisture. After that, the water potential starts to drop. Varieties such as Merlot or Grenache do not show any response until 14 percent of soil moisture in a silt loam soil.

At the other end of the continuum, varieties such as Semillon or Chardonnay drop leaf water potential continuously, in a straight line from well-watered to stressed soil conditions.

Having this information allows growers to determine how much to irrigate and even when it’s not necessary.

Research will continue

Now, with funding from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Specialty Crop Block Grant program, she will continue with three more years of data collection, teaming with some researchers in the Bordeaux region of France and collaborating on some commercial vineyard trials with grower Jim Holmes.

Martinez’s current and future research can make the irrigation process more precise and allow growers to base their decisions on their own soils and vineyards, not a mathematical model from a university, said Holmes, who owns Ciel du Cheval Vineyard in the Red Mountain viticulture area near Benton City, Washington.

Holmes is known for sophisticated irrigation measuring tools. He already uses pressure bombs in both leaves and other plant material and has soil moisture sensors recording data every 15 minutes.

Overall, the wine grape industry has become quite skilled at water stressing vines, Holmes said. “The question becomes, ‘Why do anything more?’” he said. “Well, it’s because there’s more to learn.” •

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment