When Spanish wine executives Jesús and Ana Martínez Bujanda first built a winery in Walla Walla, folks expected them to do things the Spanish way.

Instead, they planted varieties other than Tempranillo, used irrigation and trellises, hired a Walla Walla winemaker and viticulturist and followed the lead of locals who had already built a successful, if young, industry in the Pacific Northwest.

“We came here to learn,” Jesús said. “We didn’t come here to try to do the things the way that we do them in Spain.”

In 2019, the family opened Valdemar Estates in Walla Walla, a hub for wineries in southeastern Washington.

The overall company, called Valdemar Family, is based in La Rioja, a province in northern Spain that is known for Tempranillo and has a wine history dating back to medieval monasteries. The family had been wanting to expand but couldn’t find the right fit in Europe. Jesús asked them to consider Washington, where he had visited as a University of Washington international studies student in 2008. After some visits and networking, they settled on Walla Walla.

Shortly after, the family hired Devyani Isabel Gupta, a graduate of the Walla Walla Community College viticulture and enology program, as an assistant winemaker. Now, she serves as winemaker and viticulturist. She also has degrees in psychology and Spanish from Whitman College, another Walla Walla school.

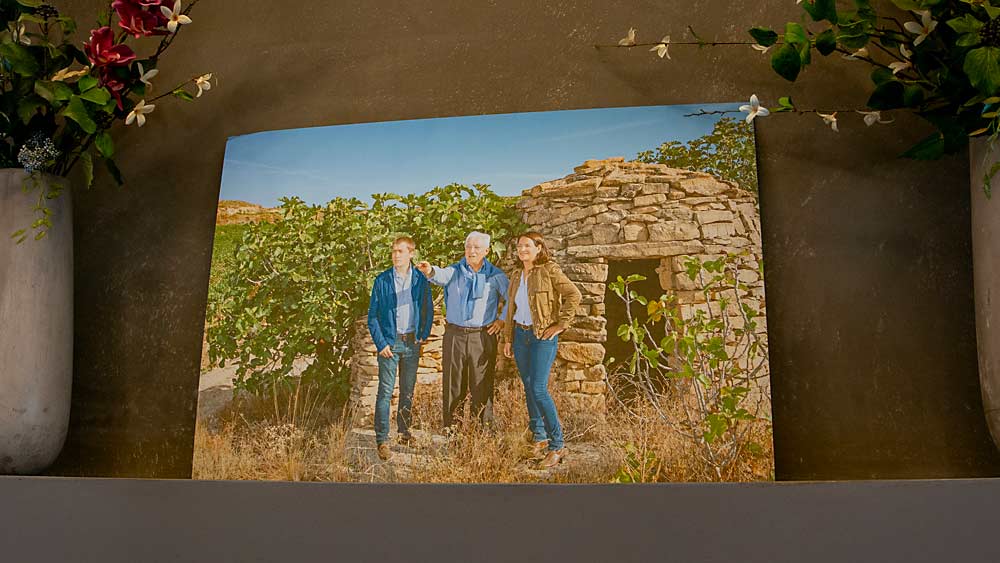

Today, Jesús is the CEO of Valdemar Family and lives in Walla Walla. Ana is the chief operating officer and lives in Spain. Their father, Jesús Sr., is the president but has semiretired to an advisory role, also in Spain.

“He’s a very, very good taster because he has a lot of experience,” Ana said during a visit to Walla Walla in June.

Their mother, Carmen, is not involved with the business.

Ana has two adult children in Spain. Both have expressed at least some interest in becoming the sixth generation. Jesús’ children are still young.

Ana said she will likely remain in Spain for her career but communicates with Jesús and the Walla Walla team every day by video conference to discuss the differences and similarities of diseases and pests.

“The best thing is that we’re learning a lot,” she said.

Differences and similarities

Despite the family’s commitment to Washington, they imported a few European ideas, giving the two veins of their business similarities and differences.

The two locations operate on a different scale. Valdemar Estates currently produces about 3,500 cases per year but has capacity for about 10,000. Their winery in Spain, called Bodegas Valdemar, cranks out 120,000 cases annually, exporting about 75 percent of that volume.

Business decisions differ, too. For one, variety selection and management practices in America are up to individual businesses. Most growers have contracts, but companies may plant and harvest as much as they want. In Europe, appellations authorize the use of grape varieties and regulate yields.

Valdemar Estates’ business tactics hearken to Spain’s emphasis on food. The Walla Walla winery features a tapas restaurant, and in September the company opened a tapas cocktail and wine bar in Woodinville. Also, they harvest a little earlier than their neighbors, seeking a fresher style that pairs better with food, Jesús said.

Both wineries export to each other through their existing distribution networks, so European drinkers in eight countries are exposed to the Walla Walla wine.

The vineyards are a mixture of old- and new-world ideas, too.

They have plenty of the horizontal cordons common in the Northwest, but Gupta head-trains the company’s Grenache into tall, three-cane goblets. It’s a style common in Europe, though other growers in parts of the Walla Walla Valley are trying it, too.

“This is based off of what I saw at the family’s estate in Rioja,” said Gupta, a Washington State Wine Commission board member, pointing to some vines in April, just as they started budbreak.

However, she uses trellis wires to make the fruit hang higher, away from drip irrigation lines. The vineyards in La Rioja are freestanding and have no irrigation.

Valdemar Family has been partnering with Washington State University to trial Spanish varietals in Washington and plans to plant one of them, Maturana Tinta, in the next couple of years.

Shoutout to Washington

Valdemar’s decision to adopt Washington techniques is a testament to the state’s industry, said Erik McLaughlin, CEO of Metis, a Walla Walla food and beverage consulting company.

“It’s a great validation of Walla Walla and of Washington state that they want to come and embrace and be part of it rather than transplant and do something different,” said McLaughlin, who consults for Valdemar Estates and sold a vineyard property to the company.

They could have succeeded with Tempranillo, McLaughlin said. Several high-end wineries in Washington and Oregon produce it (see “Tempting with Tempranillo”).

McLaughlin sees Valdemar Estates as part of a trend of European mainstay wine producers investing in the American West. One factor may be that income and inheritance taxes are lower in the United States. European wineries consider the United States the largest market in the world for bottles at the high end of the price point, though demand for bargain wine has dipped.

“The U.S. is really seen as the growth area,” McLaughlin said.

Valdemar also asked for technical help from locals, including Kevin Pogue, a geology professor at Whitman College and author of the petition to form the Rocks District, a federally recognized subset of the Walla Walla Valley American Viticultural Area.

Meanwhile, other local wine leaders encouraged their new Spanish neighbors. Norm McKibben, founder of Pepper Bridge Winery and one of Walla Walla’s pioneer wine producers, helped the siblings find property and sold them a parcel for the winery next to his Amavi Cellars.

McKibben said the family takes a “long view” of winery ownership, which is good for the Walla Walla community and Washington wine industry.

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment