As the Washington wine industry focuses on sustainability, growers should consider cultivar choice as part of the equation, said Michelle Moyer, Washington State University viticulture extension specialist.

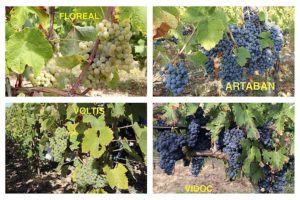

“Disease-resistant varieties are part of the sustainability toolbox,” she said as she introduced a tasting of wines made from disease-resistant cultivars on Feb. 8, the opening morning of WineVit, the convention hosted by the Washington Winegrowers Association.

Attendees tried four white wines and, when polled as to their favorite, a fairly even split of those in attendance voted for each one. Then, Moyer revealed the selections as: the traditional Gewürztraminer with one of its descendants, Traminette, which was developed by Cornell University’s grape breeding program; Aromella, another Cornell grape with Traminette parentage; and Itasca, a relatively new cold-hardy grape developed by the University of Minnesota.

Following the tasting and the reveal, the breeders from the University of Minnesota and Cornell shared presentations via video with updates about the research and grape cultivar development in their respective programs. Karl Lund, a viticulture advisor with University of California Cooperative Extension, shared insights from research into rootstock breeding and phylloxera resistance.

In Minnesota, the breeding program has long focused on developing cultivars that can survive the region’s brutal winters, said breeder Matt Clark. For over 100 years, the program has looked to the native grapes found in the region.

“Native grapes here in our backyard… are an excellent tool for grape breeders in this country and a resource for breeders around the globe,” he said. “The advantage of native plants is they’ve evolved with the native pests and diseases.”

In addition to breeding for vines that can survive winter lows of minus 35 degrees Fahrenheit, Clark said he looks for selections that “hold their buds tighter and don’t break early, which can be risky for growers, especially with climate change.” Selections that harden off quickly in the fall and acclimate to winter also support growers in climates with variable fall and spring conditions.

Cornell grape breeder Bruce Reisch shared updates on disease-resistance research. With federal funding over the past 10 years, a research project known as VitisGen and VitisGen2 has made vast advances in understanding grapevine genetics and developing DNA markers for traits delivering powdery mildew resistance, downy mildew resistance, self-fertility and fruit quality traits.

“At the seedling stage, it helps us to pick out which seedlings have genes for disease resistance that we want, way before we can challenge them with powdery mildew. Way before we can even see fruit, we can extract DNA and see which seedlings have the traits of interest,” Reisch said.

These tools allowed him to eliminate some 80 percent of the new seedlings before they were even planted in the vineyard last year, he said. That saves time and money as they search for the cultivars of the future.

And the future for disease-resistant cultivars to be accepted into wine production is approaching, he added. Yes, everything new faces an uphill battle against cultivars with centuries of name recognition, but young consumers like to try new things, and the next generation may be attracted to the story of new cultivars that dramatically reduce the need for pesticide applications and deliver great wines.

As a sign of progress, he pointed to a recent decision by the European Union to allow disease-resistant cultivars in production of appellation wines.

WineVit continues on Feb. 9 and 10 at the Three Rivers Convention Center in Kennewick, with sessions on the state’s new sustainability certification, the economic outlook for the industry, labor challenges in the vineyard, mechanization, marketing and more. For program details go to: winevit.org.

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment