Farming in 40 hours

Washington’s overtime mandate for agricultural workers begins its phase-in process this month, and this is the first of several stories Good Fruit Grower plans to publish examining the impacts on the fruit industry. This story looks at the workers’ perspectives on overtime mandates in California and Washington, while future stories will include guidance from experts on how to remain in compliance with regulations and how growers are adapting their management.

Farm labor has never been lucrative for Artemio Hernandez, a married father of three.

Bouncing around from vineyards and pear orchards in the Central Valley to cherry blocks in the Northwest puts food on his table and barely pays the rent of his Lodi, California, apartment.

But an overtime mandate intended to improve his life instead has made things worse, he said. “It didn’t work.”

For decades, farmworkers have been exempt from a federal law mandating 1.5 times normal wages for hours that exceed 40 per week, but in recent years, a wave of states have passed or are considering laws that remove the exemption. Over the past year or so, Good Fruit Grower has interviewed nearly two dozen West Coast agricultural laborers like Hernandez about how such laws have affected their lives. Though far from a representative sample, interviews included workers who migrate between states and crops, some who work through contractors and some who are longtime, year-round employees. Supervisors were present in some interviews and out of earshot in others.

None of the workers interviewed saw a benefit. They liked the idea of overtime pay, but they understood that farms operating on narrow margins would rather alter operations to avoid letting overtime accrue, effectively capping their weekly earnings.

That’s what seems to be happening so far.

Take River Valley Orchards of Grandview, Washington, for example. In 2020, before the state passed its phased-in overtime requirements, the company temporarily pared hours to 40 to avoid retroactive overtime wage claims. Manager Lupe Muñoz said employees were upset and work fell behind schedule.

Muñoz would prefer to use his already trained crews for extra work but will try to hire more employees instead to avoid the extra cost, he said. If he can’t find more workers, his farm will just have to pay some overtime.

“We know we may have to,” Muñoz said.

How the overtime mandates will affect the agricultural economy depends on how farms — already facing rising labor expenses and stagnant prices — handle the conundrum. Do they find more workers, mechanize when possible or bite the overtime bullet if they can afford it — or a mixture of all three? Meanwhile, farmworkers burdened with rising costs of living face a future where hours may become more scarce.

California has head start

In 2021, when California’s phased-in overtime threshold was 45 hours, Hernandez earned about $600 per week to prune, harvest, spray and drive tractors on farms throughout the Central Valley. He expects that to decline slightly in 2022. His rent costs $1,200 per month in a city known for a spiking housing market and a growing homeless population. He takes second jobs for a couple of extra hours a day. His wife, Laura, could work — and has in the past — but child care would run roughly $1,100 per month for their three kids.

Like farmworkers across the country, Hernandez typically has relied on income from long hours, when they were available, to see his family through the slow winter months. He and his brothers and cousins travel to Washington and Oregon almost every year to pick cherries at piece rate and were alarmed to hear those states have made or are considering similar overtime changes.

In reaction to California’s overtime mandates, the Hernandez family has cut back on expenses, eating more vegetables and less meat. Hernandez has also noticed a shift in relationships with supervisors, who now face their own pressures to do more with less manpower.

“I just want to speak up for my people,” Hernandez said. “Because they work hard, but they are also very vulnerable.”

A political history

Overtime as a rule started in 1938 with the U.S. Fair Labor Standards Act, passed to combat the high unemployment of the Great Depression. The law also created a national minimum wage and many of the enforceable workplace safety standards still in place today. Farmworkers were exempt, to give agricultural producers a way to hire high-volume temporary positions. In 1966, farmworkers were granted minimum wage but not overtime.

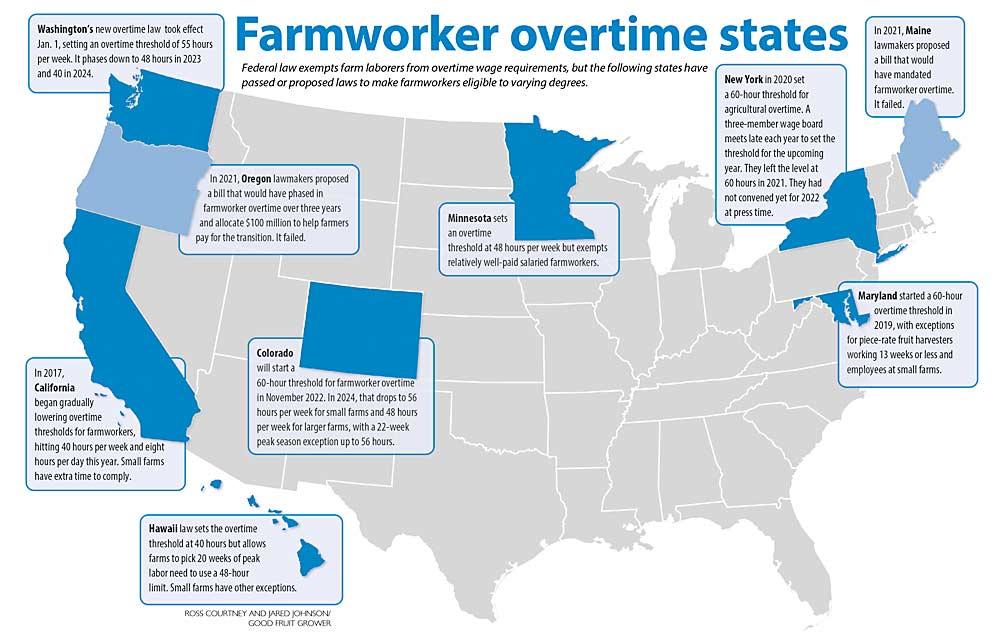

That difference between farming and other industries is now eroding. So far, seven states have removed agricultural workers from the overtime exemption, to varying degrees, according to Farmworker Justice, a Washington, D.C., labor advocacy organization.

California went first in 2017, gradually lowering the threshold over three years. It hits 40 hours this year, same as any other industry.

New York followed with the Farmworker Fair Labor Practices Act that set a 60-hour workweek threshold for agricultural overtime in 2020 and created a three-member wage board to recommend yearly changes. The panel stood pat for 2021 because of the pandemic. As of Good Fruit Grower’s publication deadline, the panel had not reconvened to set 2022’s level. Lowering the floor to 40 hours would drive up New York farmers’ labor expenses by 17 percent, according to an economic impact report by Farm Credit East, an agricultural lending cooperative serving North Atlantic states.

In Washington, a 2020 State Supreme Court decision in favor of dairy workers who challenged the overtime exemption prompted state lawmakers to grant all agricultural laborers overtime in 2021, phasing it in over three years. Maryland, Colorado, Hawaii and Minnesota all have new laws that make farmworkers eligible for varying degrees of overtime, while in 2021, Oregon and Maine lawmakers introduced farmworker overtime bills that did not pass. Oregon Rep. Andrea Salinas has said publicly she intends to try again.

In recent years, U.S. legislators, including Arizona Rep. Raúl Grijalva, have made several attempts to mandate farmworker overtime nationwide, including his current House Resolution 3194, the Fairness for Farm Workers Act.

Proponents

Labor advocates don’t buy the argument that overtime mandates hurt the workers they’re intended to protect. If farmers need more work after 40 hours, they can often pay their existing workers at time-and-a-half for a lower cost than hiring additional workers, considering the added expense of recruiting, training, taxes and benefits, said Bruce Goldstein, president of Farmworker Justice, which has advised and testified in some of the states that made overtime changes.

He’s not surprised some farmworkers want to work extra hours. They just should receive a premium like any other employee in America, he said. Besides plenty of farmworkers do favor the overtime laws.

“There is absolutely no reason we shouldn’t already be seen as equal under the law,” three farmworkers, Rodolfo Mendez, Martir Zambrano and Jorge Ramirez, wrote in a New York Daily News op-ed column. “There is no reason that farmworkers seeking union protections shouldn’t already have this as a baseline for our pay, just like everybody else.” The three men are members of the union Agricultural Workers United of New York. The state’s new wage law also made it easier for farmworkers to unionize.

In Oregon in early December, two workers and a legal nonprofit filed a petition with the Oregon Court of Appeals challenging state regulations that exempt farmworkers from overtime, The Oregonian reported.

Workers who object likely worry their farms might go out of business, Goldstein said. “If workers are being told that disaster will strike if overtime is passed, well of course they’re going to say they don’t want that.”

Farmworker Justice also opposes seasonal exceptions to overtime, which some states have enacted. Other seasonal industries — construction, retail and tourism — manage to survive without exceptions. Above all, the group considers overtime a fairness issue. Most U.S. farmworkers are Latino and are being paid under wage laws that advocates contend were intended to leave out Black workers decades ago.

“It’s time that this long-standing racial inequity is ended,” Goldstein said.

Reaction from employees

In California, the staggered overtime restrictions have cut into the family recreation of Demetrio Martinez, an operator for a Madera farm that grows nuts and figs. For years, he worked long hours during the week to reserve weekends to take his kids to the beach or Yosemite National Park, both within two hours of his home.

“Now I can’t do it,” he said.

He supplements his income with yardwork gigs but still tries to save Sunday afternoons for his family. Several fellow employees shared his opinion.

In Washington’s Yakima Valley, Guillermo Cabrera’s orchard employer adjusted to coming overtime laws by putting him on a salary. The longtime foreman was not in favor of the change.

“They should consult people like me before they pass this crazy, stupid law,” said Cabrera, who now worries about the future of the farm that helped him put two children through college.

“What if it’s time for me to go home and I’m not done yet?” he said. “I feed my family from here. What’s going to happen to this place?”

Callers to Radio KDNA, a Spanish-language public radio station in the Yakima Valley, told broadcast hosts that employers had been reducing normal-time wages to leave some room in their budgets for overtime.

Octavio Ansar and Roberto Muñoz, both longtime employees of River Valley Orchards in the Yakima Valley, expect to look for second jobs as Washington’s overtime rules take effect. “I have to do something different to pay my bills and stuff,” said Muñoz, a married father of two and brother of the manager, Lupe Muñoz. His wife also works in farming.

Oregon likely will be the next state battlefield. In a survey by the Oregon Farm Bureau, more than 40 percent of responding farmers said an overtime mandate would increase their labor costs by at least $50,000 or more per year. More than 50 percent of growers said they would adjust by mechanizing, reducing their workforce or revising schedules. Less than 20 percent said they would pay overtime.

Lesley Tamura, a fourth-generation Hood River, Oregon, pear grower, is part of a work group helping Rep. Salinas find a compromise between agricultural employers and labor advocates.

“We’re not against an overtime policy,” Tamura said. “We would love our workers to make more money, but we don’t have any more money to give.”

Among the considerations are phasing in thresholds over three years, allowing seasonal exemptions, establishing a taxpayer-supported fund to help smaller farms make the transition, and granting flexibility to allow employees to work more hours one week to make up for weeks shortened by inclement weather.

Farmers can’t simply pay workers the same way other industries do, she said.

“We are different than other industries.”

—by Ross Courtney

Washington state debate continues

The debate over agricultural overtime in Washington is not over, even though a new law mandating it took effect Jan. 1.

State Sen. Curtis King, a Yakima Republican, plans to seek changes to the new law that would grant farms the ability to exceed overtime thresholds during seasons of peak labor need, such as harvest, King said. Republicans in the state House of Representatives have similar plans, and even some Democrats have shown support, he said.

However, the state lawmakers, who convene Jan. 10, will have their hands full.

“It’s a controversial bill to begin with and it’s a short session, so you just don’t know,” King said. The measure will contend for attention and time with other contentious issues, such as police reforms.

King and farm groups such as the Washington State Tree Fruit Association sponsored the overtime mandate legislation in 2021 to avoid exposure to retroactive wage claims related to a State Supreme Court ruling that declared overtime exemptions for dairy workers unconstitutional. The new law applies the mandate to all farmworkers, phasing in the threshold over three years — 55 hours in 2022, 48 hours in 2023 and 40 hours in 2024.

Last year, King and his supporters tried to include a seasonal caveat that would have allowed farmers to select 12 weeks of high labor needs each year to work employees up to 50 hours without paying that required 1.5 times wage. That exception was revised out of the bill in committee, against King’s objection, though he voted in favor of the revised bill on the Senate floor, just to keep it alive, he said.

Seasonality clauses have precedent. Colorado mandates farmworker overtime but allows an exception of 22 weeks at 56 hours, while Hawaii does the same for 20 weeks at 48 hours.

Farmworkers have been exempt from federal overtime laws since 1938. Washington passed its own agricultural labor exemption in 1959 under the state Minimum Wage Act.

—R. Courtney

Leave A Comment