—by Ross Courtney

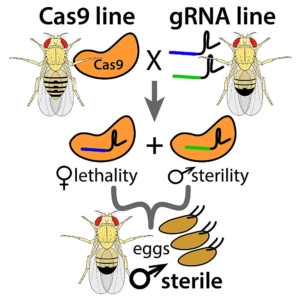

A genetics company and an Oregon State University entomologist spent the summer releasing sterile male spotted wing drosophila genetically edited to not reproduce.

Outdoors. Without nets or cages. And nothing bad, which genetic engineering skeptics might have feared, actually happened.

“They seem to stay fairly local,” said Chris Adams, who led the project for OSU.

That was the primary lesson from an experiment with genetically sterilized SWD by Adams and Agragene, a St. Louis company rooted in research funded by the West Coast cherry and blueberry industries.

In Adams’ experience, SWD — the tiny, invasive fruit flies threatening soft-fruit industries — stay close to home, traveling but a few trees away, at most. The experimental, genetically altered versions followed the same habit, Adams said.

That result is critical to allowing the so-called precision-guided sterile insect technique to move forward. The idea is that someday, the sterile male flies will mate with females, who will then lay unviable eggs, crashing the population of the invasive pest and protecting fruit.

Sterile insect technique has been around for decades, such as the 30-year-old codling moth control program that uses moths sterilized by radiation treatments at a facility in British Columbia. Gene-editing offers a new approach to producing sterility.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture granted Adams and Agragene an experimental permit to make weekly releases of genetically edited (GE) males in a 1-acre block of cherries at the university’s Mid-Columbia Agricultural Research and Extension Center in Hood River. The team had two questions: 1) Will the edited SWD stay near their release site and not disperse into the wild? 2) Will the sterile males successfully mate with females to reduce the wild population?

Adams and Agragene say the first question was answered “yes.” Adams placed monitoring traps in and around the orchard, full of shady, humid canopies and plenty of fruit for egg laying — SWD heaven. His team only caught the GE flies near the release site, according to traps verified by Agragene in St. Louis.

Question No. 2, however, remains unanswered. The hot summer took a toll on all SWD — gene-edited or not — so whether the mating trick worked was inconclusive.

Application and history

Adams suspects the sterile insect technique will help U-pick and organic growers, where insecticides are limited, or in habitats surrounding orchards, such as the plentiful thickets of native Himalayan blackberries in the Columbia River Gorge, one of the West Coast’s prolific cherry-production areas.

“I see this as a really good tool to control these flies where you can’t catch up with them,” he said.

Also, SWD in pockets of California are showing resistance to key insecticides.

Research into other forms of biological control is ongoing as well, such as a parasitic wasp under study around the U.S. and a yeast-based biopesticide in trials at the University of California, Davis.

The sterilization research started years ago with projects by Omar Akbari, a genetics researcher at the University of California, Riverside. He later moved to UC San Diego and co-founded Agragene in 2017. The company purchased the intellectual property from the university in 2019.

In 2022, the company hired Stephanie Gamez (who earned her doctorate working on the projects under Akbari) as the research and development director, and the company moved to St. Louis, where laboratory and insectary space is less expensive, said CEO Bryan Witherbee. That’s where they rear the bugs, shipping them to Adams in cardboard boxes that hold 2,000 each.

The whole system is designed to end with unfertilized eggs, so the edited genes die when the bugs die. Agragene touts three years of data proving 100 percent sterility. All of the males in the boxes are completely sterile; none has ever accidentally made it through the process unedited.

“We’ve done a lot of work to prove that out,” Witherbee said. “There’s no possible way for those genes to transmit into the rest of the world.”

Agragene is applying with the U.S. Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service for more permits to repeat the experiment at Hood River and add other locations, Witherbee said. •

Leave A Comment