The X disease epidemic continues to threaten Washington cherry orchards, but a team of Washington State University researchers shared new insights into management of the disease (which is often referred to under the umbrella term of little cherry disease) and the magnitude of the problem during a Tuesday morning presentation at the Washington State Tree Fruit Association Annual Meeting.

In recent years, growers have reported pulling out almost 150,000 cherry trees due to either X disease or little cherry disease, said WSU pathologist Scott Harper. That’s 685 acres of cherries, along with more than 180 acres of stone fruit. He estimated the lost productivity will cost the industry about $80 million, when you consider the cost of replanting and the time it takes for new orchards to come into production as well.

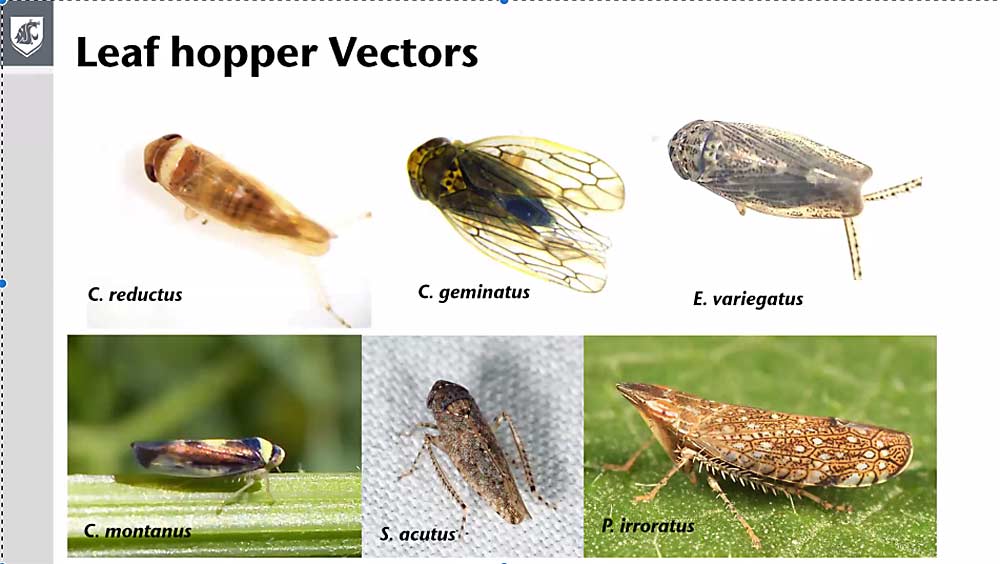

Most of the research presentations focused on X disease, which is caused by a phytoplasma pathogen that’s vectored by leafhoppers. Little was known about these insects before researchers discovered their role as a vector.

WSU entomologist Louis Nottingham shared findings from his insecticide efficacy trials to find the most effective conventional and organic products to recommend. For organic growers, he found two pyrethroids, Azera and PyGanic, were quite effective in his lab trials, while conventional products Asana, malathion and Actara “all were very effective at killing leafhoppers,” he said.

The critical timing for leafhopper control is from harvest to the end of the season, Tobin Northfield, another WSU entomologist, said.

But he and his graduate students are also studying how leafhoppers behave in orchards and what other plant hosts could be serving as reservoirs of the pathogen, in the hopes of finding long-term control strategies. Perennial broadleaf plants common in and around orchards, such as mallow, dandelion, alfalfa and clover, offer great habitat to the leafhoppers, Northfield said. Data from a trial this summer showed that using reflective mulch as a ground cover, covering up those host plants, reduces leafhopper activity in orchards, he said.

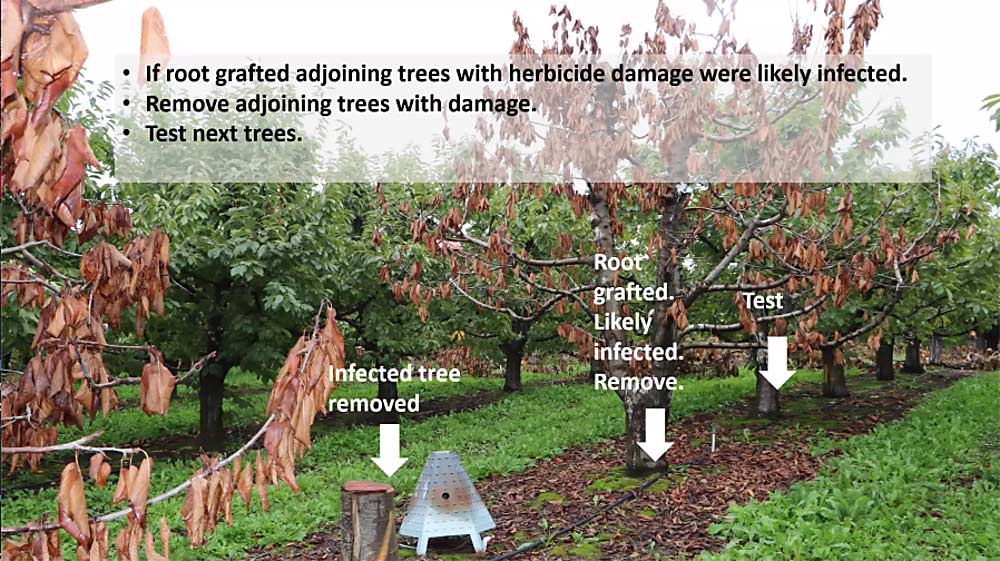

WSU extension specialist Tianna DuPont shared findings from case studies on tree removal as well. In older cherry blocks on larger rootstocks, she recommends using herbicide treatment on stumps, to see if root grafting results in herbicide injury.

“In the smaller rootstocks, we don’t see as much herbicide moving, indicating that we have less of a problem with root grafting,” DuPont said, and therefore, less of a need to do the herbicide treatment.

Several of the speakers stressed that thorough scouting for symptoms just before harvest is key to detecting the disease, followed by prompt removal of symptomatic trees.

“The challenge is that the symptoms can be missed as unripe fruit until closer to harvest,” Harper said. “People don’t think of it as a disease, they just think the fruit is not ripening.”

Symptoms can vary by cultivar and can be more subtle in early infections, he said. As the infection progresses, it becomes more obvious, but the earlier growers can detect infected trees and remove them, the better. For a visual guide to symptoms in different cultivars and tips on scouting, visit WSU’s resources website.

Other talks in the Tuesday morning session focused on invasive insect pests, including the brown marmorated stink bug and the Asian giant hornet.

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment