2017 Grower of the yeawr, Mike Omeg, stands in one of his blocks of cherries — he owns 330 acres in the northern Oregon hills east of the Cascade Mountains. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

Mike Omeg collects bugs and keeps them in jars. He pokes holes in the lids so they can breathe. He has a queen ant in a test tube between cotton balls.

Know how hard it is to find a queen ant, he asks? Pretty hard. She just laid eggs. Look closely and you can see them.

Omeg is 42 years old and has a master’s degree in entomology, though he has always done this — collected critters from the natural world he finds so fascinating around his home in The Dalles, Oregon. His mom and her Jack Russell terrier once stumbled across a garter snake in his bedroom.

“The snake and I met eye to eye under a piece of furniture,” she recalled. A neighbor came over to help her move it outside “where it belonged.”

He was that kid, and in so many ways still is.

Mike Omeg, who has a master’s degree in entomology, shows a live walking stick insect that he is caring for in his office. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

But it goes way beyond animals. Omeg approaches every aspect of running his 330-acres of scattered cherry orchards with the same boyish sense of wonder.

Mike Omeg, Omeg Family Orchards

He plants native pollinator habitat and identifies the tenants as they swirl around the blooms. He builds trellis systems so tall his employees joke the posts can be seen from space.

He boasts when he finds fungus growing on the roots of one of his baby trees; it’s a good fungus, not a bad one, and of course he knows the difference.

“He always had a great interest in knowledge for the sake of knowledge,” said his father, Mel.

Meanwhile, everything he learns he shares with other growers. He’s involved with countless trials and participates in nearly every educational tour in the Northwest, and if there’s one along the Columbia Gorge, you can bet it will stop at his place.

Omeg was selected by the magazine’s advisory board for leadership in the tree fruit industry, his inspiration to others, his passion for sharing knowledge and his commitment to quality fruit.

“We don’t live in a vacuum”

Omeg’s ancestors first farmed in The Dalles in 1905, when his great-great-grandfather moved from Germany, married a local woman and raised cattle, hay and fruit on about 160 acres in the hills overlooking the Columbia River.

Over the years, the subsequent generations gradually specialized in fruit production, joining other Columbia Gorge growers. Mike Omeg’s parents, Mel and Linda, decided to concentrate solely on sweet cherries.

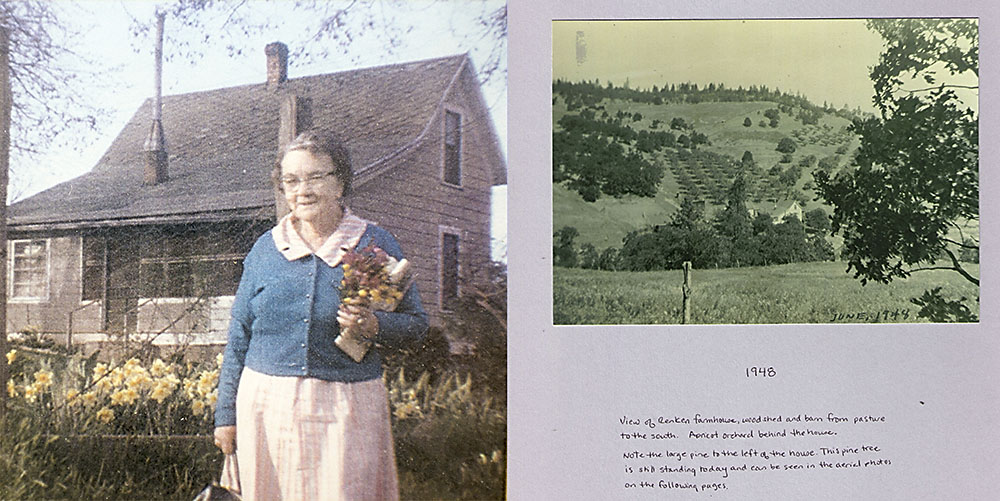

The Omeg family’s legacy in the region stretches back more than 100 years. Left, Mike Omeg’s great-grandmother Edna Renken. Right, the homestead in 1948. (Courtesy Mike Omeg)

Mike Omeg took over day-to-day management of the orchard in 2005. Today, his parents still own the land while he owns the fruit production corporation, a common arrangement between generations of a farming family.

His parents keep a cottage on the orchard property and advise him, but have retired and live off the farm. Omeg, his wife, Lindsay, and their four children, ages 2 to 7, all live in the original, but renovated, farmhouse.

On one section of Omeg Family Orchards, just past gravestones at The Dalles cemetery, stands one of the largest active cherry variety trials in the world. Home to 50 or so cultivars, the block has been there since 1996.

The Oregon State University extension service owns the trees, but the Omegs own and manage the land. Growers and researchers, both local and from as far as Australia, visit.

Omeg welcomes the attention. His farm is known for sharing information.

He speaks frequently at conferences far and wide. He posts YouTube videos about his equipment and trials. He hosts so many tour stops that researchers tease him about it.

He lives by a creed that knowledge helps everybody, and the absence of it hurts everybody. “We don’t live in a vacuum,” he said. “It’s all interconnected.”

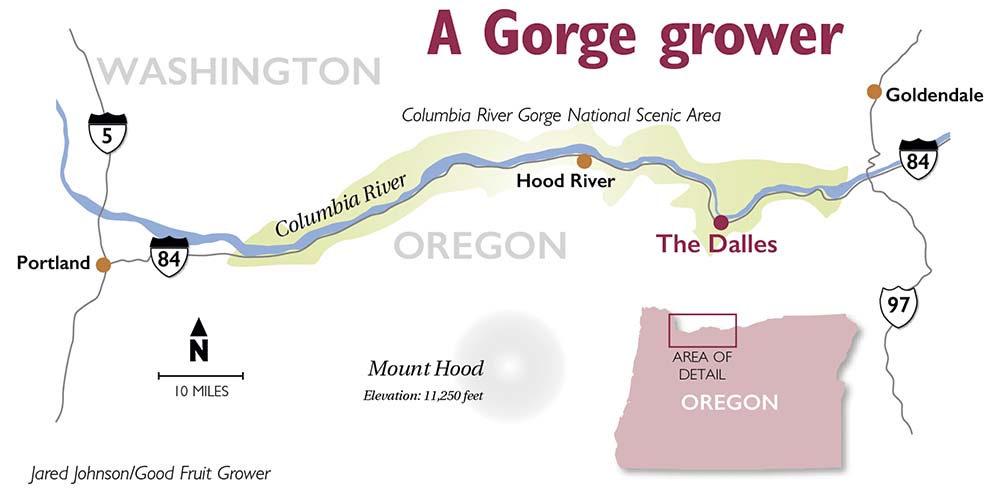

Mike Omeg, 2017 Good Fruit Grower of the Year, farms in the Oregon hills overlooking the Columbia River, outside the city of The Dalles. The Dalles is one of several communities in a 13,000-acre fruit growing region referred to as the Columbia Gorge or Mid-Columbia. The area produces about 15 percent of U.S. sweet cherries, at about 35 million tons annually. The city, population 15,000, sits nestled in the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area. The region is known for steep, hilly slopes with views of Mount Hood in the distance, an arid climate and high winds that draw windsurfers to a nearby section of the river also famed for its salmon fishing. Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower illustration

The idea dates back to his parents, both former school teachers. “Knowledge is something you don’t have to put into a bank,” Linda said. “It’s in your mind, and it grows when you share.”

Mike Omeg himself wasn’t always that way, though. When he first began helping his parents on the farm, he urged them to be more tight-lipped.

Then he started participating in tours around the world and saw how generous other growers were with information.

In 2007, a visit to Allan Bros. in Naches, Washington, one of the Northwest’s more innovative companies, cemented that idea.

After his horticultural epiphany, Omeg began to view his growing area in The Dalles — once a pioneering region — as behind the times. Only by sharing information would that change, he determined.

“I’ve learned that my dad was right,” he said.

Lynn Long, a semi-retired OSU extension horticulturist, recalled how the informational generosity of growers on some of those overseas trips impressed Omeg. If anything, Omeg has learned to share from other growers.

Mike Omeg talks to a crowd of growers during the OSU Soils Workshop in The Dalles, Oregon, on March 16, 2017. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

Omeg, a longtime member of Long’s advisory council, has plenty to share because he experiments to a greater extent than other growers, Long said. Research alone can’t drive innovation; somebody like Omeg has to lead the charge commercially.

“That’s how change in the industry takes place,” Long said.

Omeg admits he doesn’t always like the attention that comes with being so open, but feels a responsibility to tell the story of farmers and rural communities, a story he considers misunderstood in American discourse.

Still, he sometimes says no to interviews and speaking invitations to avoid getting so busy that he doesn’t have time to farm. He’s met people like that. “I don’t want to be that person.”

A political edge

Omeg is constantly seeking new techniques to maximize his production and profits. He uses equipment to burrow and set underground rodent traps, applies fish fertilizers to stimulate soil in weak blocks and mulches to improve water penetration in his ground. (Read “A grower with industry influence”)

But he cares about more than just improving his farm. He’s not shy about showing his political views.

Omeg’s pickup truck bears bumper stickers espousing immigrant rights. It’s been egged three times.

In 2007, he and some neighboring farmers marched through The Dalles in opposition to a proposal to require verified Social Security numbers for a state driver’s license. Gov. John Kulongoski later signed the executive order anyway.

Omeg believes farmers don’t speak up enough about political issues, especially immigration, letting extremists on both sides dictate the discourse. Within a day or two of U.S. President Donald Trump’s election, Omeg heard Spanish radio personalities advising listeners to flee the country at once to avoid mass federal arrests.

So, he visited his 30 or so full-time employees as they pruned to encourage calm, rational decisions.

Speaking fluent Spanish and without making promises, he told them nothing would likely happen overnight and elected officials often promise more than they can deliver. One family moved to Mexico anyway, but the rest stayed, Omeg said.

“That helped a lot for the people,” said Javier Marines, Omeg’s production manager and a 22-year employee.

Marines has stayed with the Omegs — he started when Mel and Linda ran the orchard — so long because the family provides opportunities for workers to learn new skills, something he thought was missing at his previous workplaces.

They taught him to drive tractors and operate sprayers and have sent him to conventions. Every year, they give him a raise, though he has never asked for one. “I know he’s doing the same for everybody.”

Omeg also gets a lot of attention for his environmental views. He argues that outspoken activists on both sides too often vilify each other, while middle-ground growers get painted with a broad brush.

Omeg has surrounded his home and office with wildlife habitat to bring beneficial bugs to surrounding orchards. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

Omeg has planted wildlife habitat, protected beneficial insects and invested in mulching equipment that mows the center of his alleys and blows the cuttings under his rows. He is participating in a long-term soils trial with Long.

But when speaking about soil health, Omeg usually couches the techniques in terms of the bottom line: Healthy soil is good for business; land stewardship is good for business.

Omeg acknowledges an environmental bent to his beliefs, hoping to foster land that will support five more generations of his farming family, but does not consider himself an activist. He has attended conferences at which he was booed by both sides.

“If you say to a farmer, ‘Is improving your soils good or bad? Is reducing the toxicity of your plant protection products … good or bad for your business and your workers and the people who consume your product?’ I think people would say yes to those things. But the environmental community has attacked the agricultural community and the agricultural community historically has felt that their way of life was threatened because of that.”

Failures

His longtime neighbor, Bob Bailey, the former majority owner of neighboring Orchard View Farms, considers Omeg more progressive in his ideas, especially about soil health, but is glad for the differences.

Omeg calls Bailey a trusted adviser. About 12 years ago, Bailey warned Omeg that grafting from one variety to another wouldn’t work, Bailey said. Omeg disagreed but was wrong.

The trees never produced, and he ended up ripping them out. Omeg laughs at his mistake, and Bailey appreciates the humility.

“He’s progressive,” said Bailey, who has known Omeg since he was a boy. “It’s good to have people in the industry who are doing that and who say, ‘Well, I made a mistake.’’’

Omeg is candid about other failures, too. In the 1990s, he and some area growers invested in an agricultural weather network to help develop more growing degree-day models for pest control.

Omeg managed the project through his private consulting business at the time. It didn’t work out, and he lost a lot of the money put up by some of his longtime farming friends.

“I got to take my lumps early about what it’s like to have a business completely fail,” he said.

A few years later, however, he worked with a grant writer from the National Resources Conservation Service to fund the weather network as a nonprofit salmon protection program. The Dalles area farmers use it to this day.

It’s clear Omeg derives endless enjoyment from life as a farmer. In some respects, he’s still that wide-eyed farm boy collecting bugs.

During an August family vacation at his parent’s home in Lincoln City, he led his four children, two nieces and the child of a family friend on a bug hunt in the nearby woods. They turned over every log, rock and even most of the house’s paving stones, and the kids all had fun. “He still has that excitement,” Linda said.

Exciting, but he sees risks.

Technically savvy and progressive, Omeg wonders if his skill level will sustain him through the next 30 years of automated harvesters and other machines.

His labor pool will become more complicated once he starts H-2A next year. And orchards will continue to require more capital investment, making the cost of a mistake even higher.

He agrees with a speaker he once heard: Farmers won’t be farmers in the future, they will be engineers.

He also expects more farm consolidation, a daunting thought for himself, a relatively small grower who does not have his own packing facilities to allow him to hire specialists.

“It’s exciting,” he said, but at the same time, “I just think it’s going to be a lot harder to be a farmer.” •

– by Ross Courtney / photos by TJ Mullinax

Leave A Comment