Trina McAlexander grew up knowing she wanted to take over the family farm: a diverse fruit orchard and farm stand in the long shadow of Oregon’s Mount Hood.

She went even further: Just five years after buying the farm from her parents, McAlexander has reinvented the farm with an event space, a wine and cider tasting room and a brewery that draw people to the farm for more than just a box of fruit.

Sure, visitors still buy fruit, but they also drink it and eat it atop the farm’s popular pear pizza, said McAlexander, who now owns Mt. View Orchards, Grateful Vineyard and Mountain View Brewing. The new businesses support each other and make it economically viable for the family to continue to farm the 50 acres that her family has called home for more than 60 years.

“It was a pretty sobering moment, buying the farm in 2015,” McAlexander said. “When I looked at the books, it was like, ‘We are going to lose our way of life here if we don’t get scrappy and come up with other ways of funding the farm.’”

Adding agritourism ventures has always been a way to boost farm revenue, said Audrey Comerford, the agritourism specialist with Oregon State University Extension. It’s a nebulous term, but Comerford defines agritourism as anything that brings people to the farm and helps to sell whatever the farm is producing, from traditional U-picks and hayrides to a new generation of on-farm cideries and breweries.

“Folks are looking for different ways to keep family farms afloat,” Comerford said. Younger growers especially seem to recognize the opportunity in people’s desire to enjoy a farm experience.

“If the pandemic has taught us anything, it’s shedding even more positive light on these operations,” Comerford said, adding that she’s optimistic those trends will continue.

Inviting more people

In her mission to expand the farm’s revenue, the first move McAlexander explored was event hosting, as the aptly named Mt. View Orchards offers a fabulous view of Mount Hood.

A fellow farmer who also hosts weddings to supplement income walked her through the process.

“It’s been a learning curve, but it’s also been really special,” she said. “People get connected to our farm and then they come back every year to pick fruit.”

Halfway across the country, Ecker’s Apple Farm in southwest Wisconsin has also supplemented farm income by hosting weddings. Co-owner Jess Ecker said she was inspired to explore that new business after hosting her own wedding on the farm in 2015.

“You have to buy so much infrastructure to do your own wedding, so we thought we might as well keep doing it,” she said.

But they limit the wedding season to the early summer months, so it doesn’t conflict with the 1,500 or so people who come to the farm on a fall Saturday for apples, apple pie and a beer or cider in their beer garden.

Ecker and her sister, Sara, who run the farm together, have, like McAlexander, been adding more revenue streams to their 40-acre farm since they inherited it 13 years ago. They said the key to their success has been finding their agritourism niche. They started a “chill” beer garden, for example, while neighboring Ferguson’s Orchards offers all the exciting kid activities.

“We’re really good with pie. We’re good at caramel apples,” Jess Ecker said. The beer garden sells hard ciders made from their fruit by a local winery, but when they secure the license to make it themselves, they plan to continue to have their juice pressed off-site, said Sara Ecker. They invite a food truck to the beer garden to free up their own commercial kitchen to focus on the hundreds of pies their mother bakes each day.

“Knowing what infrastructure you want to tackle matters. You don’t have to tackle it all,” Sara Ecker said.

More family businesses

Hosting events inspired McAlexander to try her hand at making hard cider, something she’d dabbled with in college, at scale to supply the events and bring more value to the farm’s fruit. So, the next year she invested in cidermaking capacity. She also planted some grapes.

Before she knew it, McAlexander had partnered with her aunt and uncle, who own Elk Cove Vineyards in the Willamette Valley, to start producing wine under her own label, Grateful Vineyard.

“So, then I thought we should have a tasting room,” she said. “Each next step made sense. We had the tasting room, so now let’s get the brewery done, let’s serve our own beers.”

She was already selling fruit to local cider and beer producers, so she knew the demand was there. Plus, “there’s something special about drinking beer on the farm where the fruit was produced,” she said.

With each new venture comes the opportunity for more revenue — but also a lot more work. That can help a family farm create additional employment for more family members, as is the case for the Eckers, as well as give the next generation a chance to bring their own ideas to the business, Comerford said.

For McAlexander, both factors played in. Her parents, now in their 70s, continue to work in the orchards and help the farm market customers. Her brother, Ryan, an experienced chef, runs the kitchen for the tasting room, where his signature pear pizza showcases the farm’s fruit. She’s hired staff to harvest fruit, work the restaurant, make the beer and manage events.

“I don’t have to be involved in everything now. We have the team to make it happen,” she said. “I still work off-farm as a nurse practitioner; I couldn’t make my land payments otherwise.”

Traditions and modernizations

Creative thinking about income diversification can be critical to keeping small family farms in business, she said. She’s eager to share her story in hopes that it can help others.

“I am really passionate about farms staying in families,” she said. “As farmers, we need more emphasis on helping one another and finding ways to promote one another.”

For example, the Hood River Fruit Loop encourages people to make a day trip out of a visit to the region, visiting farm stands, wineries, cideries and restaurants. Such collaborative agritourism promotions powerfully enable farm communities to support one another, Comerford said.

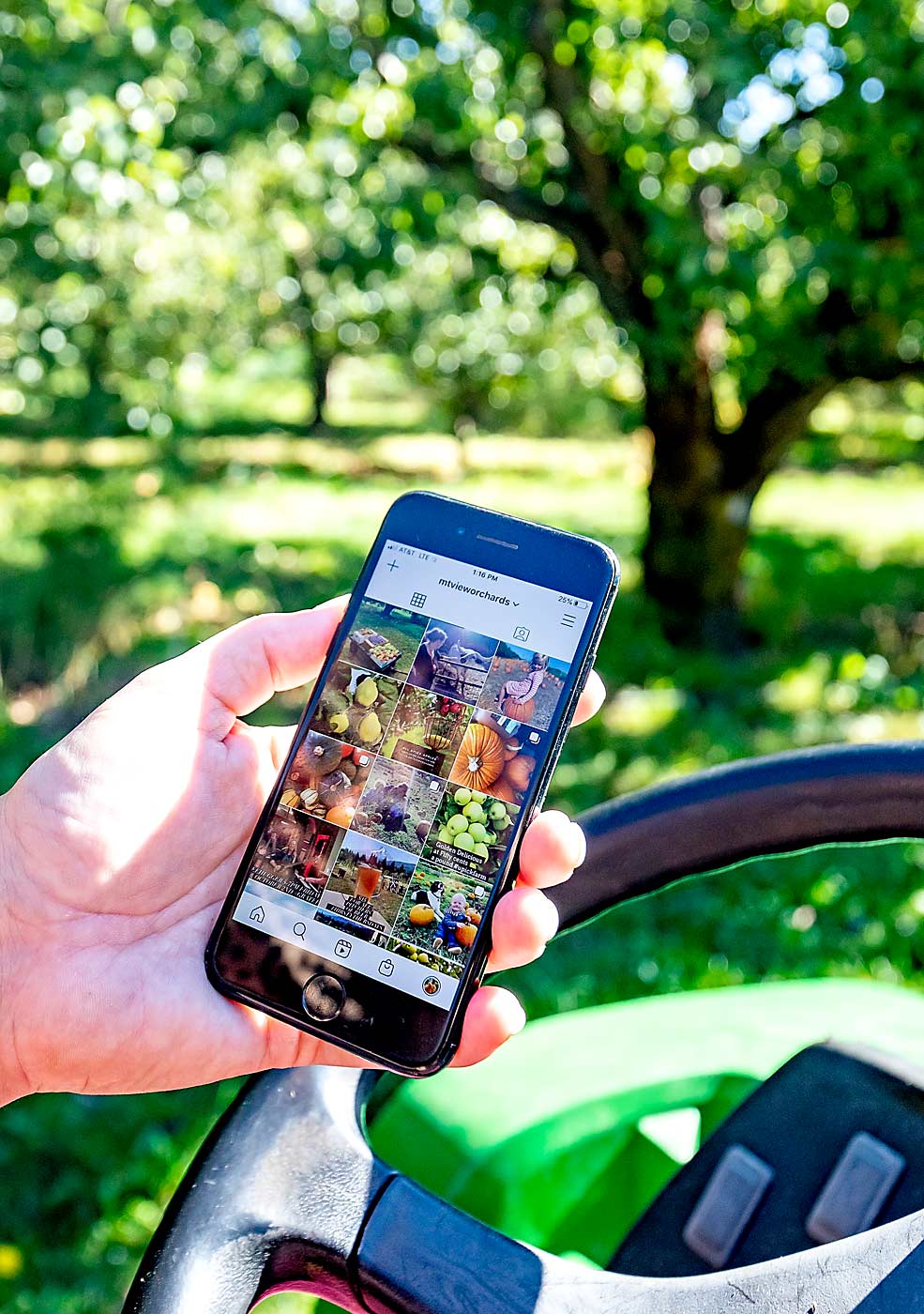

Self-promotion can be a difficult skill for many farmers to learn, McAlexander said, but she’s seen the benefits of sharing images and stories from her farm on Facebook and Instagram.

“You gotta learn social media and invite people to share what you are doing,” McAlexander said. “It’s not about your comfort level. It’s about selling your product and promoting your farm.”

The business ventures are new, but they also fit with longstanding family tradition: Her great-grandparents, who emigrated from Switzerland, carried values of farming, fermentation and hospitality that still inspire McAlexander today, she said.

“I know not every farmer wants people on their farm, but if you come from a family where hospitality is a big deal, it feels like you are sharing your property,” she said. “Inviting people to hang out on the farm, it’s been a dream come true.”

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment