As this is the last article in this series, I decided to provide a brief overview of the history of the fruit box label, as described in The Ultimate Fruit Label Book, which I authored (with the help of many others).

As this is the last article in this series, I decided to provide a brief overview of the history of the fruit box label, as described in The Ultimate Fruit Label Book, which I authored (with the help of many others).

Between the years of about 1880 and 1956, millions of colorful paper labels were used by fruit and vegetable growers to identify and advertise boxes of fresh produce. Since most pieces of fruit were individually wrapped and then packed and shipped in wooden boxes, potential buyers could not see or handle the product they were being asked to purchase. In the early years of the fruit industry, this was not an insurmountable problem.

Production was relatively low, wholesalers worked closely with individual growers, and the distribution network was regional at best. However, the arrival of the railroad, improvements in production, and a growing demand for fresh produce throughout the United States and abroad led to increasingly stiff competition as well as national and international sales. Fruit growers and packers were forced to find a clever way to label, advertise, and market their crops.

However, Pacific Northwest growers were slow to recognize the value of a colorful label, even when other food product industries, especially the marketing arms of California citrus and Pacific Northwest salmon packers, did. Overall, the fruit industry in the Northwest was shy about taking on the extra expense of having labels designed, printed, delivered, stored, and pasted onto boxes.

First large order

Prior to about 1910, the majority of apple boxes were stamped or stenciled with only the most basic information (i.e., variety, size, grower’s name, and location), even though there is some evidence that a few growers saw the value in labels as early as the 1890s. The first documented large order of box labels did not occur until 1907, when the Yakima County Horticultural Union placed an order for 25,000 labels, but most boxed fruit contained either no identification or simply a stenciled name of the grower and type of fruit.

By about 1913, labels were becoming recognized as a necessity for informing the buyer and consumer about what the box contained and where the fruit was grown and packed. Printers employed some of the best designers of the day to help growers and packers develop eye-catching images. Schmidt Lithograph and Traung Label & Lithograph, both of San Francisco, as well as Spokane Lithographic Company of Spokane, Washington, were among the most prolific printers. They printed labels in the tens of thousands, bundled them in stacks of one thousand, and shipped them to growers throughout the country.

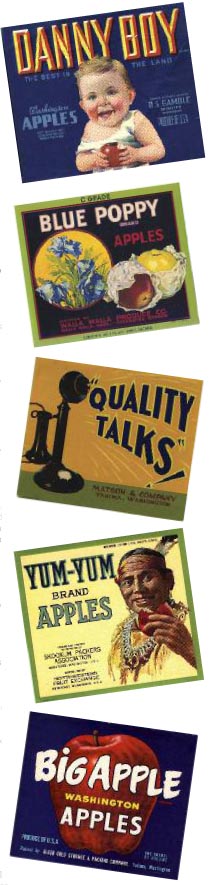

Generally speaking, there were just two types of fruit box labels produced: private labels and stock labels. Both types are roughly the same size, and both types eventually had a distinctive background color corresponding to the grade of the apple, no matter what overall label design was featured—blue was for extra fancy, red for fancy, and green, white, or yellow for the C grade. Private labels are those custom-designed and printed for an individual grower, packer, or marketing association. Stock labels, in contrast, were mass-produced and generic; many growers would use the same label that would differ only by the overprinting of the name of the specific grower.

This need for visual appeal and brand-name recognition led to great successes, great rivalries, and the desire to create ever more exciting, eye-catching images. A “good label,” said a trade journal of the day, was one that would “dignify the pack—it must catch the buyer’s attention, bring the product to mind, create a desire to buy, and motivate the sale.”

There are generally considered to have been four distinct eras of label design: the Naturalistic Era (c1885–1920), the Advertising Era (c1920–c1935), the Commercial Art Era (c1935–1955), and the Modern Era or Corrugated Carton Era (post 1955).

Cardboard

After World War II, the use of the label as an identifying tool ended relatively quickly. The shortage of labor and raw materials for the manufacture of wooden boxes during World War II, when both men and wood were more urgently needed for the war effort, encouraged growers to look for other means of packing the fruit. Inexpensive cardboard cartons that could be preprinted with a simple label or other identifying mark took over by the mid-1950s. Also contributing to the decline of the label was the decision by most growers to organize themselves into cooperatives that packed the fruit under a few simple and more generic labels.

Growers left with stocks of labels never imagined they would someday become collectible. Nevertheless, as early as the late 1960s, some people, especially interior decorators, recognized the graphic merit in what had once been exclusively a disposable marketing tool.

The stories that led to the adoption of a particular design, graphic element, or photographic image are as varied as the number of unique labels. Growers chose word plays on their own names, used pictures of their children or spouses, chose dramatic landscape scenes as a background, or had artists develop an original unique design. We will never know what inspired every label, but it is my hope that readers have learned why fruit box labels have continued to attract the fascination and interest of collectors and the general public more than 50 years after they lost their role as an effective tool in the marketing and sale of fresh fruit throughout the world.

I would like to thank all the readers who have expressed their appreciation and enjoyment of the articles as well as those who have generously shared further information and/or made corrections. The real force and knowledge behind every single story have been provided by Delmar Bice, the volunteer curator of the Yakima Valley Museum’s extensive fruit label collection. It is Del who has shared his research, his detective skills, and his passion for the many tales these bright colorful pieces of advertising art convey. I have been merely the scribe who has learned as much as you with each new issue.

Leave A Comment