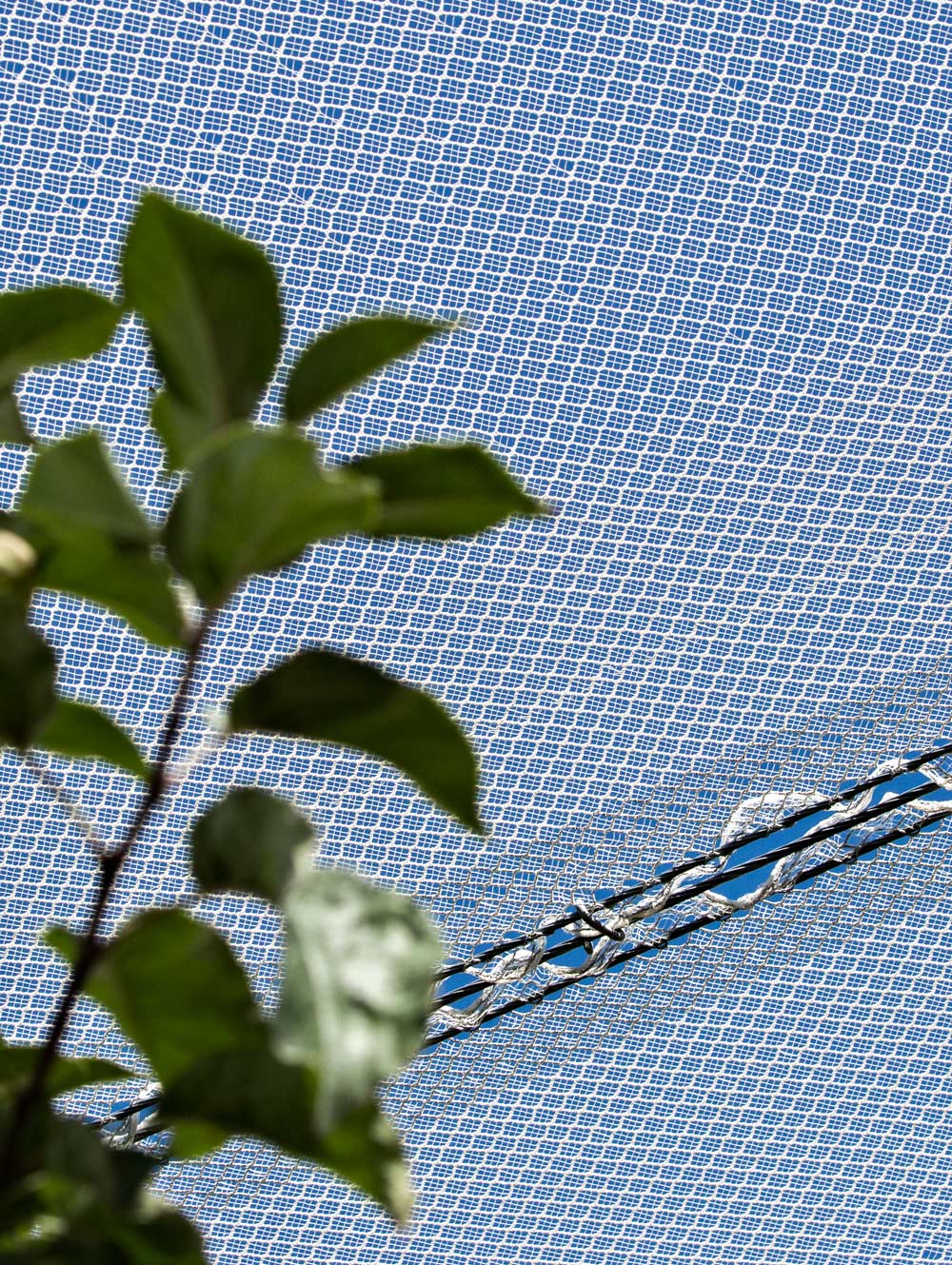

IFTA New Zealand Study Tour attendees visit one of the few Honeycrisp blocks in the country, located about six miles north of the city of Timaru in the South Island in February 2018. Because of the cooler climate in the area, this block, operated by M A Orchards, is covered from top to bottom with netting to protect the crop from hail and reflective material is brought in before harvest to help the fruit obtain an even red blush. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

Honeycrisp has found a home in New Zealand, and the home is Timaru.

Located in the central part of the country’s South Island, along its eastern coastline, Timaru sits in the Canterbury agricultural region. It’s an area long known for row crops, sheep and dairies more than tree fruit, but that could be changing.

Timaru accounts for only a small percentage of New Zealand’s apple industry overall, but a handful of growers increasingly have planted the notoriously finicky Honeycrisp to measured success.

First brought to the island in 1996, the variety opened with just small control trials. Eventually, nurseryman Andrew McGrath acquired the rights, giving him control in New Zealand over growing, grading and packing of the variety.

McGrath approached the variety with an eye toward the science, looking for the best places it might grow, before planting a single tree. “Luckily you were all ahead of us anyway, so we learned a lot about the climatic needs of the variety,” he told attendees of the International Fruit Tree Association summer tour in February.

Some of M A Orchards’ Honeycrisp weeks before harvest during the IFTA New Zealand Study Tour. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

Fruit had been grown historically in Timaru, but only at a small level. However, sitting at about 44.4 degrees south latitude, the region is known for slightly cooler summer temperatures. On average, a 29-degree day (84 degrees Fahrenheit) would be considered a hot one in Timaru, McGrath said, which appears to suit the variety well. (Note: This summer has been more extreme, with several South Island cities experiencing record high temperatures in January.)

Weather in the Timaru area is generally favorable for growing Honeycrisp, however hail can be a problem so M A Orchard managers are installing netting that allows for ample sunlight but protects the crop from hail. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

“We chose it because of the ability of this area to color the fruit, and the trees don’t get stressed at all. There’s a sea breeze that blows backward and forward, and the latitude is similar to Minnesota where it was bred,” McGrath said.

So far, about 140 hectares (345 acres — 1 hectare is slightly less than 2.5 acres) of Honeycrisp have been planted in the Timaru area, though it’s only been grown commercially since about 2012, strictly as a managed variety to control quality and maximize grower returns.

At M A Orchards, a partnership of McGrath and Washington state grower Bruce Allen of Columbia Reach Orchards, IFTA attendees visited two of the company’s five blocks.

The first: a sixth-leaf block reaching roughly 12 feet high, largely planted on Geneva 202 and Malling 9 rootstocks in 4-by-12 spacing with a tree density of 1,850 trees per hectare (about 750 trees per acre).

The M.9 trees produce bigger apples, and keeping that fruit size down poses the biggest challenge of the rootstock, orchard manager Red Martin said.

The high canopy is covered with white hail netting that is not retracted in winter, since the area isn’t expected to ever receive the kind of snowfall or high winds that could bring it down.

Today, the netting costs about $40,000 to $50,000 in New Zealand dollars per hectare, with a lifespan of 10 to 15 years.

Light reduction under the nets is about 15 to 18 percent, and honeybees haven’t had any problems flying under them, Martin said.

The orchard brings in about four hives per hectare during pollination. “We bring the same bees back every year, and they seem to develop an intelligence,” he said.

Red Martin

The tall system also doesn’t restrict use of a three-row sprayer, with a grass strip every third row.

Growers also visited a fourth-leaf block planted on mostly G. 202, with some M.9 and M.26, planted at 2,900 trees per hectare (about 1,175 trees per acre) in a V trellis, five wires on each side. Overall tree height is nearly 9 feet.

Laterals are pulled down slightly onto the wires — not too early to prevent spurs on year-old wood — with pruning to two buds, a resting bud and a fruiting bud.

Martin noted that in the U.S., growers usually leave two fruiting buds, “but we have a bit more vigor here, and one usually blows out.” In addition, the six- to eight-week growing season after harvest allows buds time to recover. “That’s a long season.”

Fire blight hasn’t been a problem at M A Orchards, Martin said. Rather, European canker poses the biggest challenge, where management means “we basically have to remove the tree.” They also spray regularly for powdery mildew, starting at around blossom on a twice-weekly cycle, and for apple scab.

Overall, Martin said the goal is for 35,000 linear meters per hectare of fruiting wood in the vertical orchard, versus 30,000 on the V-trellis, with none inside. The yield target is 80 metric tons per hectare, or 80 bins per acre.

Bitter pit hasn’t been a problem. McGrath said they’ve found they don’t want to be waiting for fruit to color on the tree, which leads to internal fruit problems. Fruit is not shipped with controlled atmosphere. “We want exposed fruit that we can pick early,” he said. “We can get a lot of overbrowning, over maturity, and if we pick a bit unripe, we get scald.” •

Watch (360 VR capable)

Walk with Andrew McGrath through one of his Honeycrisp blocks thriving in New Zealand’s Pleasant Valley. (Be sure to use your mouse in a web browser or move your mobile device around to “look” around the apple block.)

—by Shannon Dininny / photos/video by TJ Mullinax

Leave A Comment