Spending half a million dollars on a new harvester doesn’t necessarily sound like a budget-conscious decision, but in light of increasing labor costs, mechanizing vineyard tasks from pruning to harvest could save some Washington wine grape growers real money.

The impact on your bottom line depends on how well your vineyards can adapt to mechanization and the size of your operation. But with Washington’s minimum wage going up 43 percent from 2016 to 2020, even mid-sized growers could start to see the investment in equipment pencil out in their favor, said Ken Ballard, relationship manager for Northwest Farm Credit Service based in Pasco, Washington.

Ken Ballard

“What we spend for labor is going to increase dramatically though 2020,” Ballard said in a talk at the Washington Winegrowers’ annual convention in Kennewick in February. Part of that is attributable to the state’s minimum wage and part is increasing competition for a limited pool of skilled farm workers. “Tree fruit, your competitors for labor, they aren’t as automated in the field as you guys are, and I think they are going to put pressure on the market that will make it harder for you.”

It’s not just a concern in Washington. Minimum wages in California are set to rise $1 every year for the next five years, reaching $15 an hour in 2022 for larger employers and in 2023 for companies with fewer than 25 employees. In New York, wages are set to rise 29 percent from 2016 to $12.50 per hour in 2020, with additional increases toward $15 an hour to be set in the future for areas outside New York City, where wages increase faster.

Of course, a shiny new machine doesn’t just arrive in your vineyard and make everything easy and efficient.

Growers should expect to invest their time, and a lot of trial and error, into figuring out how best to use mechanized tools such as precision pruners in their operations. That was the message from a panel of growers who offered tips on mechanization at the convention.

Assuming that you’re willing to do the work to incorporate new tools and have a trellis system that’s compatible with mechanization, the biggest factor in whether you’re investing wisely in mechanization is size.

“Are you big enough to be able to adopt it and have the fixed costs be surpassed by the economies of scale?” Ballard asked. “If you just have one machine, and it goes down at harvest, that’s a problem.”

Based on his cost estimates, a new $500,000 mechanized harvester with precision pruning and destemming and sorting capabilities costs approximately $86,000 a year when financed over seven years, not including operations and maintenance costs.

Ballard recommends estimating the savings per acre of switching labor-intensive tasks like harvest, pruning or leafing over to mechanization and multiplying that by your acreage to see if your farm is big enough to break even or profit on a new machine.

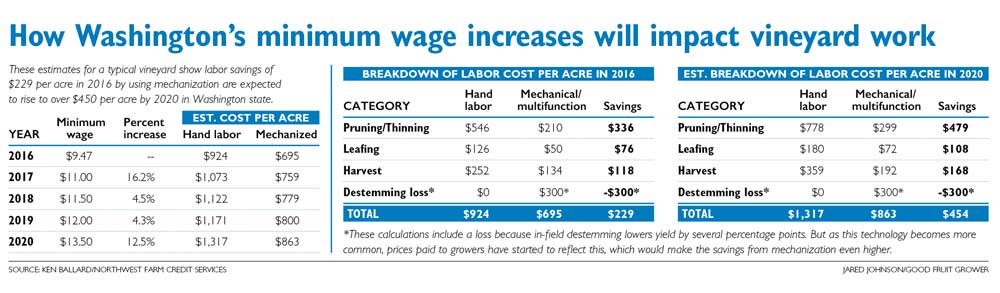

Based on his calculations, which Ballard called rough estimates, at the 2016 Washington minimum wage of $9.47 an hour, vineyard work by hand costs about $924 per acre and mechanized about $695 per acre. With that savings of $229 an acre, it would take a farm of 377 acres to break even on the cost of the new machine.

But by 2020, when minimum wages in Washington will be $13.50, the savings per acre grows to $450. That means a grower needs just 190 acres to break even on the new machine. And at 300 acres, growers would save $50,000 a year with mechanization.

These estimates for a typical vineyard show labor savings of $229 per acre in 2016 by using mechanization are expected to rise to over $450 per acre by 2020 in Washington state. (Source: Ken Ballard/Northwest Farm Credit Services. Graphic by Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower)

Included in these figures is a $300 per acre loss for mechanization, due to the destemming and sorting technology on new harvesters that results in lower yields by several percent, since material other than grapes is removed in the field. That can cut into payments for independent growers who are paid by the ton, so Ballard included those losses in his estimates.

But after the presentation, several growers told Ballard that this technology is becoming the norm and prices for clean grapes now often reflect the lost weight due to cleaner grapes. That makes the financial advantage for mechanization likely even higher than his estimates, Ballard said in a follow-up interview.

Of course, everyone’s numbers will look a little different, depending on existing vineyard systems and practices. But it’s undeniable that increasing labor costs means mechanization is increasingly appealing and cost-effective. “I’m not saying it’s right for you, but with the rising cost of labor, if you are not mechanizing, it might be time to look at it,” Ballard said.

Moreover, if more mechanization becomes necessary to stay profitable for 200-acre farms and make a lot of money for 400-acre farms, it’s going to continue to pressure growers to get bigger or get out. •

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment